Trump Administration Cancels $1 Billion in Grants for Student Mental Health

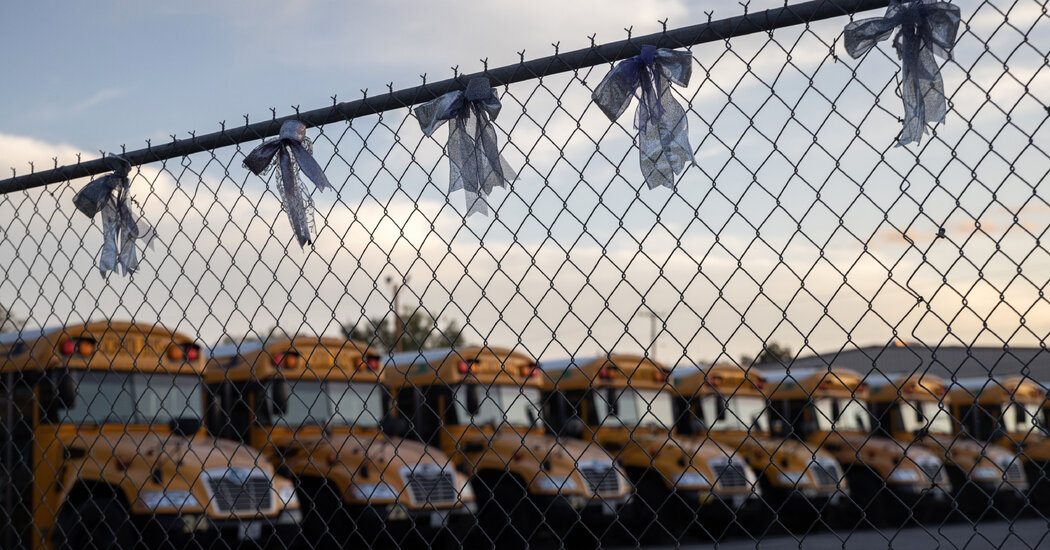

Congress authorized the money in a bipartisan breakthrough around addressing gun violence after a shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, killed 19 children and two teachers.The Trump administration has halted $1 billion for mental health services for children, saying that the programs funded by a bipartisan law aimed at stemming gun violence in schools were no longer in “the best interest of the federal government.”Lawmakers authorized the money in 2022 after a former student opened fire at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, killing 19 children and two teachers and injuring 17 others. The measure, known as the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, broke a decades-long impasse between congressional Republicans and Democrats on addressing gun violence by focusing largely on improving mental health support for students.But just as some of the mental health programs are starting, the Education Department canceled the funding this week and informed grant recipients that they would have to reapply for the money because of potential violations of federal civil rights law.The department did not specify a civil rights law or provide the grant recipients with any evidence of violations, according to the notice reviewed by The New York Times.An Education Department spokeswoman confirmed that the grants had been discontinued because of a particular focus on increasing the diversity of psychologists, counselors and other mental health workers.“Under the deeply flawed priorities of the Biden administration, grant recipients used the funding to implement race-based actions like recruiting quotas in ways that have nothing to do with mental health and could hurt the very students the grants are supposed to help,” said Madi Biedermann, the department’s deputy assistant secretary for communications. “We owe it to American families to ensure that taxpayer dollars are supporting evidence-based practices that are truly focused on improving students’ mental health.”We are having trouble retrieving the article content.Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.Thank you for your patience while we verify access.Already a subscriber? Log in.Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Read more →