How Exercise May Help Protect Against Severe Covid-19

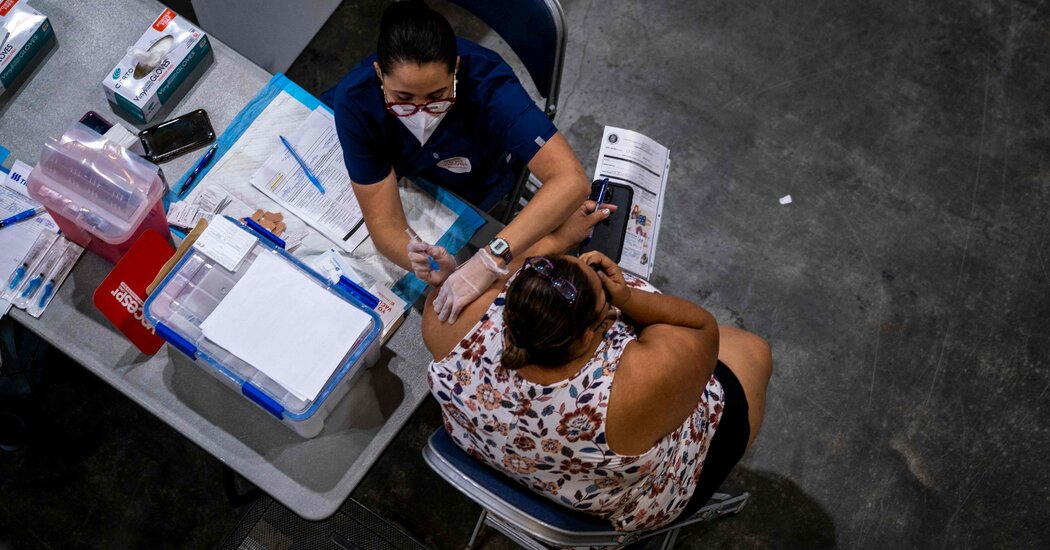

People who tended to be sedentary were far more likely to be hospitalized, and to die, from Covid than those who exercised regularly.More exercise means less risk of developing severe Covid, according to a compelling new study of physical activity and coronavirus hospitalizations. The study, which involved almost 50,000 Californians who developed Covid, found that those who had been the most active before falling ill were the least likely to be hospitalized or die as a result of their illness.The data were gathered before Covid vaccines became available and do not suggest that exercise can substitute in any way for immunization. But they do intimate that regular exercise — whether it’s going for a swim, walk, run or bike ride — can substantially lower our chances of becoming seriously ill if we do become infected.Scientists have known for some time that aerobically fit people are less likely to catch colds and other viral infections and recover more quickly than people who are out of shape, in part because exercise can amplify immune responses. Better fitness also heightens antibody responses to vaccines against influenza and other illnesses.But infections with the novel coronavirus are so new that little has been known about whether, and how, physical activity and fitness might affect risks for becoming ill with Covid. A few recent studies, however, have seemed encouraging. In one, which was published in February in The International Journal of Obesity, people who could walk quickly, an accepted gauge of aerobic fitness, developed severe Covid at much lower rates than sluggish walkers, even if the quick striders had obesity, a known risk factor for severe disease. In another study of older adults in Europe, greater grip strength, an indicator of general muscle health, signaled lowered risks for Covid hospitalizations.But those studies looked at indirect measures of people’s aerobic or muscular fitness and not their actual, everyday exercise habits, so they cannot tell us if getting up and moving — or staying still — changes the calculus of Covid risks.So, for the new study, which was published Tuesday in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, researchers and physicians at Kaiser Permanente Southern California, the University of California, San Diego, and other institutions decided to compare information about how often people exercised with whether they wound up hospitalized this past year because of Covid.The Kaiser Permanente health care system was well suited for this investigation, because, since 2009, it has included exercise as a “vital sign” during patient visits. In practice, this means doctors and nurses ask patients how many days each week they exercise, such as by walking briskly, and for how many minutes each time, then add that data to the patient’s medical record.Now, the researchers drew anonymized records for 48,440 adult men and women who used the Kaiser health care system, had their exercise habits checked at least three times in recent years and, in 2020, had been diagnosed with Covid-19. The researchers grouped the men and women by workout routines, with the least active group exercising for 10 minutes or less most weeks; the most active for at least 150 minutes a week; and the somewhat-active group occupying the territory in between.The researchers gathered data, too, about each person’s known risk factors for severe Covid, including their age, smoking habits, weight, and any history of cancer, diabetes, organ transplants, kidney problems and other serious, underlying conditions.Then the researchers crosschecked numbers, with arresting results. People in the least-active group, who almost never exercised, wound up hospitalized because of Covid at twice the rate of people in the most-active group, and were subsequently about two-and-a-half times more likely to die. Even compared to people in the somewhat-active group, they were hospitalized about 20 percent more often and were about 30 percent more likely to die..css-1xzcza9{list-style-type:disc;padding-inline-start:1em;}.css-rqynmc{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:0.9375rem;line-height:1.25rem;color:#333;margin-bottom:0.78125rem;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-rqynmc{font-size:1.0625rem;line-height:1.5rem;margin-bottom:0.9375rem;}}.css-rqynmc strong{font-weight:600;}.css-rqynmc em{font-style:italic;}.css-yoay6m{margin:0 auto 5px;font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.125rem;line-height:1.3125rem;color:#121212;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-yoay6m{font-size:1.25rem;line-height:1.4375rem;}}.css-1dg6kl4{margin-top:5px;margin-bottom:15px;}.css-16ed7iq{width:100%;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;justify-content:center;padding:10px 0;background-color:white;}.css-pmm6ed{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}.css-pmm6ed > :not(:first-child){margin-left:5px;}.css-5gimkt{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:0.8125rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-letter-spacing:0.03em;-moz-letter-spacing:0.03em;-ms-letter-spacing:0.03em;letter-spacing:0.03em;text-transform:uppercase;color:#333;}.css-5gimkt:after{content:’Collapse’;}.css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;-webkit-transform:rotate(180deg);-ms-transform:rotate(180deg);transform:rotate(180deg);}.css-eb027h{max-height:5000px;-webkit-transition:max-height 0.5s ease;transition:max-height 0.5s ease;}.css-6mllg9{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;position:relative;opacity:0;}.css-6mllg9:before{content:”;background-image:linear-gradient(180deg,transparent,#ffffff);background-image:-webkit-linear-gradient(270deg,rgba(255,255,255,0),#ffffff);height:80px;width:100%;position:absolute;bottom:0px;pointer-events:none;}#masthead-bar-one{display:none;}#masthead-bar-one{display:none;}.css-1pd7fgo{background-color:white;border:1px solid #e2e2e2;width:calc(100% – 40px);max-width:600px;margin:1.5rem auto 1.9rem;padding:15px;box-sizing:border-box;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-1pd7fgo{padding:20px;width:100%;}}.css-1pd7fgo:focus{outline:1px solid #e2e2e2;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-1pd7fgo{border:none;padding:20px 0 0;border-top:1px solid #121212;}.css-1pd7fgo[data-truncated] .css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transform:rotate(0deg);-ms-transform:rotate(0deg);transform:rotate(0deg);}.css-1pd7fgo[data-truncated] .css-eb027h{max-height:300px;overflow:hidden;-webkit-transition:none;transition:none;}.css-1pd7fgo[data-truncated] .css-5gimkt:after{content:’See more’;}.css-1pd7fgo[data-truncated] .css-6mllg9{opacity:1;}.css-1rh1sk1{margin:0 auto;overflow:hidden;}.css-1rh1sk1 strong{font-weight:700;}.css-1rh1sk1 em{font-style:italic;}.css-1rh1sk1 a{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;text-underline-offset:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-thickness:1px;text-decoration-thickness:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#ccd9e3;text-decoration-color:#ccd9e3;}.css-1rh1sk1 a:visited{color:#333;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#ccc;text-decoration-color:#ccc;}.css-1rh1sk1 a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}Of the other common risk factors for severe disease, only advanced age and organ transplants increased the likelihood of hospitalization and mortality from Covid more than being inactive, the scientists found.“Being sedentary was the greatest risk factor” for severe illness, “unless someone was elderly or an organ recipient,” says Dr. Robert Sallis, a family and sports medicine doctor at the Kaiser Permanente Fontana Medical Center, who led the new study. And while “you can’t do anything about those other risks,” he says, “you can exercise.”Of course, this study, because it was observational, does not prove that exercise causes severe Covid risks to drop, but only that people who often exercise also are people with low risks of falling gravely ill. The study also did not delve into whether exercise reduces the risk of becoming infected with coronavirus in the first place.But Dr. Sallis points out that the associations in the study were strong. “I think, based on this data,” he says, “we can tell people that walking briskly for half an hour five times a week should help protect them against severe Covid-19.”A walk — or five — might be especially beneficial for people awaiting their first vaccine, he adds. “I would never suggest that someone who does regular exercise should consider not getting the vaccine. But until they can get it, I think regular exercise is the most important thing they can do to lessen their risk. And doing regular exercise will likely be protective against any new variants, or the next new virus out there.”

Read more →