Membranes unlock potential to vastly increase cell-free vaccine production

By cracking open a cellular membrane, Northwestern University synthetic biologists have discovered a new way to increase production yields of protein-based vaccines by five-fold, significantly broadening access to potentially lifesaving medicines.

In February, the researchers introduced a new biomanufacturing platform that can quickly make shelf-stable vaccines at the point of care, ensuring they will not go to waste due to errors in transportation or storage. In its new study, the team discovered that enriching cell-free extracts with cellular membranes — the components needed to made conjugate vaccines — vastly increased yields of its freeze-dried platform.

The work sets the stage to rapidly make medicines that address rising antibiotic-resistant bacteria as well as new viruses at 40,000 doses per liter per day, costing about $1 per dose. At that rate, the team could use a 1,000-liter reactor (about the size of a large garden waste bag) to generate 40 million doses per day, reaching 1 billion doses in less than a month.

“Certainly, in the time of COVID-19, we have all realized how important it is to be able to make medicines when and where we need them,” said Northwestern’s Michael Jewett, who led the study. “This work will transform how vaccines are made, including for bio-readiness and pandemic response.”

The research will be published April 21 in the journal Nature Communications.

Jewett is a professor of chemical and biological engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and director of Northwestern’s Center for Synthetic Biology. Jasmine Hershewe and Katherine Warfel, both graduate students in Jewett’s laboratory, are co-first authors of the paper.

The new manufacturing platform — called in vitro conjugate vaccine expression (iVAX) — is made possible by cell-free synthetic biology, a process in which researchers remove a cell’s outer wall (or membrane) and repurpose its internal machinery. The researchers then put this repurposed machinery into a test tube and freeze-dry it. Adding water sets off a chemical reaction that activates the cell-free system, turning it into a catalyst for making usable medicine when and where it’s needed. Remaining shelf-stable for six months or longer, the platform eliminates the need for complicated supply chains and extreme refrigeration, making it a powerful tool for remote or low-resource settings.

In a previous study, Jewett’s team used the iVAX platform to produce conjugate vaccines to protect against bacterial infections. At the time, they repurposed molecular machinery from Escherichia coli to make one dose of vaccine in an hour, costing about $5 per dose.

“It was still too expensive, and the yields were not high enough,” Jewett said. “We set a goal to reach $1 per dose and reached that goal here. By increasing yields and lowering costs, we thought we might be able to facilitate greater access to lifesaving medicines.”

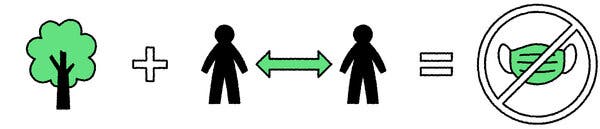

Jewett and his team discovered that the key to reaching that goal lay within the cell’s membrane, which is typically discarded in cell-free synthetic biology. When broken apart, membranes naturally reassemble into vesicles, spherical structures that carry important molecular information. The researchers characterized these vesicles and found that increasing vesicle concentration could be useful in making components for protein therapeutics such as conjugate vaccines, which work by attaching a sugar unit — that is unique to a pathogen — to a carrier protein. By learning to recognize that protein as a foreign substance, the body knows how to mount an immune response to attack it when encountered again.

Attaching this sugar to the carrier protein, however, is a difficult, complex process. The researchers found that the cell’s membrane contained machinery that enabled the sugar to more easily attach to the proteins. By enriching vaccine extracts with this membrane-bound machinery, the researchers significantly increased yields of usable vaccine doses.

“For a variety of organisms, close to 30% of the genome is used to encode membrane proteins,” said study co-author Neha Kamat, who is an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at McCormick and an expert on cell membranes. “Membrane proteins are a really important part of life. By learning how to use membrane proteins effectively, we can really advance cell-free systems.”

Story Source:

Materials provided by Northwestern University. Original written by Amanda Morris. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.