Caption: SARS-CoV-2 (pink) and its preferred human receptor ACE2 (white) were found in human salivary gland cells (outlined in green). Credit: Paola Perez, Warner Lab, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH

COVID-19 is primarily considered a respiratory illness that affects the lungs, upper airways, and nasal cavity. But COVID-19 can also affect other parts of the body, including the digestive system, blood vessels, and kidneys. Now, a new study has added something else: the mouth.

The study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, shows that SARS-CoV-2, which is the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, can actively infect cells that line the mouth and salivary glands. The new findings may help explain why COVID-19 can be detected by saliva tests, and why about half of COVID-19 cases include oral symptoms, such as loss of taste, dry mouth, and oral ulcers. These results also suggest that the mouth and its saliva may play an important—and underappreciated—role in spreading SARS-CoV-2 throughout the body and, perhaps, transmitting it from person to person.

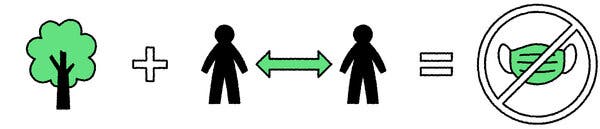

The latest work comes from Blake Warner of NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; Kevin Byrd, Adams School of Dentistry at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and their international colleagues. The researchers were curious about whether the mouth played a role in transmitting SARS-CoV-2. They were already aware that transmission is more likely when people speak, cough, and even sing. They also knew from diagnostic testing that the saliva of people with COVID-19 can contain high levels of SARS-CoV-2. But did that virus in the mouth and saliva come from elsewhere? Or, was SARS-CoV-2 infecting and replicating in cells within the mouth as well?

To find out, the research team surveyed oral tissue from healthy people in search of cells that express the ACE2 receptor protein and the TMPRSS2 enzyme protein, both of which SARS-CoV-2 depends upon to enter and infect human cells. They found the proteins to be expressed individually in the primary cells of all types of salivary glands and in tissues lining the oral cavity. Indeed, a small portion of salivary gland and gingival (gum) cells around our teeth, simultaneously expressed both ACE2 and TMPRSS2.

Next, the team detected signs of SARS-CoV-2 in just over half of the salivary gland tissue samples that it examined from people with COVID-19. The samples included salivary gland tissue from one person who had died from COVID-19 and another with acute illness.

The researchers also found evidence that the coronavirus was actively replicating to make more copies of itself. In people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19, oral cells that shed into the saliva bathing the mouth were found to contain RNA for SARS-CoV-2, as well its proteins that it uses to enter human cells.

The researchers then collected saliva from another group of 35 volunteers, including 27 with mild COVID-19 symptoms and another eight who were asymptomatic. Of the 27 people with symptoms, those with virus in their saliva were more likely to report loss of taste and smell, suggesting that oral infection might contribute to those symptoms of COVID-19, though the primary cause may be infection of the olfactory tissues in the nose.

Another important question is whether SARS-CoV-2, while suspended in saliva, can infect other healthy cells. To get the answer, the researchers exposed saliva from eight people with asymptomatic COVID-19 to healthy cells grown in a lab dish. Saliva from two of the infected volunteers led to infection of the healthy cells. These findings raise the unfortunate possibility that even people with asymptomatic COVID-19 might unknowingly transmit SARS-CoV-2 to other people through their saliva.

Overall, the findings suggest that the mouth plays a greater role in COVID-19 infection and transmission than previously thought. The researchers suggest that virus-laden saliva, when swallowed or inhaled, may spread virus into the throat, lungs, or digestive system. Knowing this raises the hope that a better understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 infects the mouth could help in pointing to new ways to prevent the spread of this devastating virus.

Reference:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 infection of the oral cavity and saliva. Huang N, Pérez P, Kato T, Mikami Y, Chiorini JA, Kleiner DE, Pittaluga S, Hewitt SM, Burbelo PD, Chertow D; NIH COVID-19 Autopsy Consortium; HCA Oral and Craniofacial Biological Network, Frank K, Lee J, Boucher RC, Teichmann SA, Warner BM, Byrd KM, et. al Nat Med. 2021 Mar 25.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Saliva & Salivary Gland Disorders (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Blake Warner (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Kevin Byrd (Adams School of Dentistry at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Read more →