SharecloseShare pageCopy linkAbout sharingZaz Hassan survived Covid but, one year on, is still living with the after-effects of the virus. “You live with the hope that you will get better,” Zaz tells me, as he takes a break from his physio class at Croydon University Hospital’s long Covid centre. “For me, the end point would be to get back to work and just play with my kids. It may take time but people are recovering, so there is still the hope that I can come out of this.”The paediatric doctor, 42, has been off work since March 2020, when he fell ill with Covid-19, at the peak of the first wave. And like many other patients, his recovery has been far from straightforward. ‘Shooting pains’After spending two weeks on a ventilator in intensive care, Zaz was discharged from hospital and felt he was slowly making progress. Then, in September, his young children returned to school. He thinks he probably picked up a cold from one of them, which “completely wiped” him out. Since then, he has been dealing with recurring symptoms, from fatigue to back problems to “shooting pain” in his legs. “It’s like when you have the flu where you absolutely can’t move and your whole body aches,” Zaz says.”You are just absolutely exhausted. The fatigue was a big thing and then I started developing the brain fog, which, for me, was not being able to find words, not being able to speak in sentences.”Long Covid: More than a million affected in February’My fatigue was like nothing I’ve experienced before’Middle-aged women ‘worst affected by long Covid”Long Covid’: Why are some people not recovering?Zaz is one of more than 1,000 patients seen by the long Covid clinic in Croydon. Another 500 are on the waiting list for diagnosis and possible referral to a specialist team for physiotherapy or a heart or lung scan. In an exercise class in the bright hospital gym, Zaz and two other long Covid patients switch tentatively from parallel walking bars to a treadmill and free weights. ‘Misjudge distances’Specialist physiotherapists help with the equipment and compare the men’s progress with previous sessions. The mood is determined – but there is frustration at the slow rate of recovery. “A couple of times I’ve felt I am going to tumble,” Zaz tells the physio he’s working with. “I misjudge distances and feel my legs are going to give way.”

BBCThe fatigue was a big thing and then I started developing the brain fog, which, for me, was not being able to find words, not being able to speak in sentencesZaz Hassan Long Covid patientDr Yogini Raste, a consultant respiratory doctor and one of the people running the Croydon clinic, says: “We see a whole spectrum of patients, from those admitted to intensive care who had a prolonged stay [in hospital] for many weeks.”Then, there are those who were never tested in the first wave, who thought they would get better at home but then started to develop a whole host of strange symptoms.”There is no universally agreed definition of “long Covid” – but it can include a broad range of health problems. The most common are fatigue and a cough, followed by a headache and muscle pain.As with any new medical condition, hard evidence about the prevalence of long Covid is difficult to come by. A survey by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) in March found about one in five people infected still had symptoms five weeks later, with one in seven still sick in some way after 12 weeks.

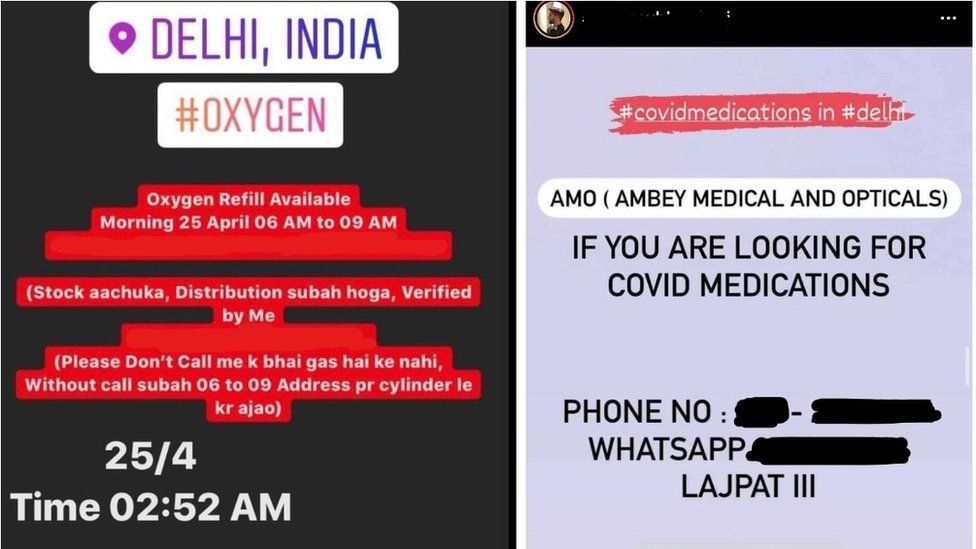

BBCWe can’t tell these patients how long it’s going to last for, so they are on a bit of a rollercoasterDr Yogini RasteConsultant respiratory doctor And the ONS estimates 1.1 million people were affected in the UK in the four weeks from 6 February. “We can’t tell these patients how long it’s going to last for, so they are on a bit of a rollercoaster,” Dr Raste says. “They might have a few weeks where they feel they are getting better and improving. “Then, just as they are coming out of that tunnel, there is another setback, so that in itself can be a great source of anxiety.”Breathing exercisesThere is no drug approved to treat long Covid. Instead, doctors try to treat individual symptoms of the condition through physiotherapy, speech therapy or breathing exercises. And in some cases, patients are referred on to specialists in cardiology, neurology and respiratory care. The NHS is now planning to open 83 long Covid clinics across England by the end of April, costing £24m in 2021, with more likely to be needed in the future. NHS England chief executive Sir Simon Stevens has said people with long-term after-effects need a “clear front-door” to know where they can access help.In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, treatment for long Covid patients tends to be through existing hospital and GP services, with some dedicated clinics for those discharged from intensive care.But some long Covid patients say they are still having to rely on internet sites for support and advice. ‘More support'”Most people and not getting answers and we appreciate that sometimes there are just no answers to give,” Aasim, one of the other patients in the Croydon physiotherapy class, says. “If you look at social-media platforms, you will see the numbers that are on support groups. We are having to speculate and be our own doctors. “Something there needs to change. We need to be taken more seriously and be given more support.”You can contact and follow Jim Reed on Twitter.What has been your experience of the pandemic? Have you had long Covid? Have you been shielding? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk.Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSayUpload pictures or videoPlease read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can’t see the form, you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk. Please include your name, age and location with any submission. LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?SYMPTOMS: What are they and how to guard against them?YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queriesTREATMENTS: What progress are we making to help people?COVID IMMUNITY: Can you catch it twice?Related Internet LinksOffice for National StatisticsLong-term effects of coronavirus (long COVID) – NHS.websiteThe BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.

Read more →