Global Partners May End Broad Covid Vaccination Effort in Developing Countries

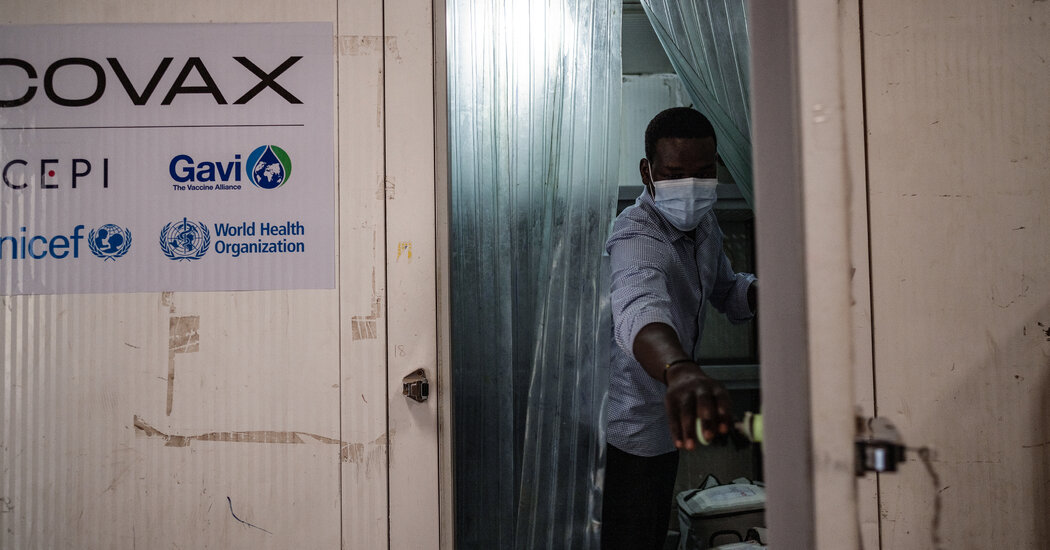

The board of Gavi, the international vaccine agency, meets Wednesday to debate shutting down the program, known as Covax, amid swiftly waning demand for the shots.The organization that has led the global effort to bring Covid vaccines to poor and middle-income countries will decide this week whether to shut down that project, ending a historic attempt to achieve global health equity with a tacit acknowledgment that the effort fell far short of its goal. The deliberations reflect the reality that demand for Covid vaccines is waning quickly throughout the world and is near nonexistent in countries that have some of the lowest rates of coverage. The program, known as Covax, has delivered more than a billion Covid vaccines to developing countries, in hugely challenging circumstances. But it was hobbled by fierce vaccine nationalism in wealthy nations and a series of missteps and misfortunes that undermined demand for the shots.The proposal to end Covax will be voted on by the board of directors of Gavi, a nonprofit, founded in 2000, that manages strategic stockpiles of emergency vaccines and supplies routine childhood shots to developing countries. The proposal would “sunset” Covax sometime in 2023. For 54 poor countries that traditionally receive Gavi support to deliver routine childhood immunizations, Covid shots would still be available for free. However, they would be rolled into Gavi’s standard immunization program, mostly as booster shots for the elderly and others in high-risk groups.Thirty-seven other countries — middle-income nations including Bolivia, Indonesia and Egypt — would receive a one-time cash infusion to “catalyze” the setting up of their own independent Covid vaccination programs.The proposal, which was obtained by The New York Times, comes from Gavi’s planning committee, whose recommendations are usually adopted largely as presented.The fate and performance of the global Covid vaccination program has become a heated issue among Gavi’s donors and the Covax partners ahead of the board meeting in Geneva — a gathering that is normally an unremarkable affair. Few of the players in the decision process were willing to speak about it on the record.Dr. Seth Berkley, the chief executive of Gavi, said the group’s work on Covid vaccination would not be diminished if the plan were adopted. “The plan in 2023 is to continue to work on getting primary coverage up as high as countries want it but also to really focus in on helping countries get those high-risk populations covered,” Dr. Berkley said. “The current proposal is that we integrate the Covax work into the core work of Gavi — not closing it down but integrating it. Because the belief is that, by the end of 2023, it shouldn’t be seen as an emergency program anymore.”Read More on the Coronavirus PandemicLong Covid: People who took the antiviral drug Paxlovid within a few days after being infected with the coronavirus were less likely to experience long Covid months later, a study found.Updated Boosters: New findings show that updated boosters by Pfizer and Moderna are better than their predecessors at increasing antibody levels against the most common version of the virus now circulating.Calls for a New Strategy: Covid boosters can help vulnerable Americans dodge serious illness or death, but some experts believe the shots must be improved to prevent new waves.Future Vaccines: Financial and bureaucratic barriers in the United States mean that the next generation of Covid vaccines may well be designed here, but used elsewhere.Currently, there is an average of 52 percent coverage of primary vaccination in Gavi-supported countries, but in some countries the figure is still below 20 percent.The World Health Organization continues to endorse a target goal of 70 percent Covid vaccination coverage. The W.H.O., a Covax partner, declined to comment on the proposal being considered by the Gavi board.Kate Elder, the senior vaccines policy adviser for Doctors Without Borders’ Access Campaign, said Gavi is moving too quickly to abandon Covax when countries have been led to expect that support would be there for years to come. “They don’t have enough analysis for this kind of huge policy decision,” she said. “But this move is driven by donors. When I speak to donors, they say, ‘We don’t want any more fund-raising for Covid-19 vaccines’.” The low demand for the vaccines means Covax has had to cancel and renegotiate purchase agreements — while high-income nations, with limited interest from their own populations, continue to funnel excess supply into the organization.Recipient countries are refusing and returning vaccine shipments, saying they have more urgent health priorities. One issue before the Gavi board this week is an effort to redouble efforts on catch-up campaigns for routine vaccinations, rates of which have declined sharply through the Covid pandemic.“Most African countries would much rather see increased investment in malaria vaccines,” said a board member not authorized to speak on the record about Gavi activities..css-1v2n82w{max-width:600px;width:calc(100% – 40px);margin-top:20px;margin-bottom:25px;height:auto;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-family:nyt-franklin;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1v2n82w{margin-left:20px;margin-right:20px;}}@media only screen and (min-width:1024px){.css-1v2n82w{width:600px;}}.css-161d8zr{width:40px;margin-bottom:18px;text-align:left;margin-left:0;color:var(–color-content-primary,#121212);border:1px solid var(–color-content-primary,#121212);}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-161d8zr{width:30px;margin-bottom:15px;}}.css-tjtq43{line-height:25px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-tjtq43{line-height:24px;}}.css-x1k33h{font-family:nyt-cheltenham;font-size:19px;font-weight:700;line-height:25px;}.css-1hvpcve{font-size:17px;font-weight:300;line-height:25px;}.css-1hvpcve em{font-style:italic;}.css-1hvpcve strong{font-weight:bold;}.css-1hvpcve a{font-weight:500;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);}.css-1c013uz{margin-top:18px;margin-bottom:22px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1c013uz{font-size:14px;margin-top:15px;margin-bottom:20px;}}.css-1c013uz a{color:var(–color-signal-editorial,#326891);-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;font-weight:500;font-size:16px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1c013uz a{font-size:13px;}}.css-1c013uz a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}What we consider before using anonymous sources. Do the sources know the information? What’s their motivation for telling us? Have they proved reliable in the past? Can we corroborate the information? Even with these questions satisfied, The Times uses anonymous sources as a last resort. The reporter and at least one editor know the identity of the source.Learn more about our process.While Covid infections are rising in much of sub-Saharan Africa, the least-vaccinated region of the world, few countries there are reporting any increase in hospitalization or death rates, one factor in the declining interest in vaccination. The low rates of serious illness and death reflect the fact that the region has a young and thus less vulnerable population, that fewer people have easy access to hospital care, and that causes of death are rarely determined or registered. All those factors may contribute to a perception that Covid is not an urgent problem.A vaccine awareness campaign in Juba, South Sudan, in 2021.Lynsey Addario for The New York TimesBut accepting low Covid vaccination rates globally could allow the virus to evolve in dangerous ways, some public health experts say. “There is still the possibility of more lethal variants emerging, and that could be a disaster,” said Philip Schellekens, a health economist who maintains the data analytics resource pandem-ic.com on pandemic inequalities across countries. “Booster momentum has come to a near halt in the developing world,” he added.Covax was badly hampered from the outset. High-income nations rushed to lock up the supply of vaccines when they were still scarce, and donations were fitful. Covax had intended to rely on a supply of AstraZeneca’s vaccine made by the Serum Institute of India in order to start deliveries in mid-2021, but the Indian government blocked the export of 400 million doses in the face of a crushing Delta variant wave.When Covax finally had vaccines to distribute, it became apparent that plans to use the routine immunization systems to deliver them were inadequate, said a Gavi board member closely involved in the rollout who was not authorized to speak publicly about the organization’s performance. The Covid shots, intended for adults and requiring multiple doses and extreme refrigeration, presented new challenges that weak health systems were ill-equipped to manage.Frustrated by the erratic supply, some public health agencies did little to create demand for the vaccines, while a cresting tide of misinformation discouraged people from seeking them out. By the time supply was adequate, Omicron, which caused less severe illness, was the dominant variant. Motivation, especially for people who would need to travel long distances or invest their own scarce resources to get a shot, had fallen away.A senior official with one of the Covax partner organizations, who was not authorized to speak publicly about the group’s work, said that some who work with the organization are referring to Covax as a “zombie mechanism.”Recipient countries don’t want Covid vaccines, but Gavi needs to move doses, and the W.H.O. has doubled down on its goal of vaccinating 70 percent of the world, the official said. “And there’s interest from many of the donors who are still trying to offload their own doses through donations to Covax,” the official added.Multiple people in senior roles with Covax partners described to The Times a monthslong and souring dispute. They said that major donors, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, had warned Gavi that it was overcommitting on vaccination orders and Covid efforts, harming its reputation because of the close affiliation with Covax failures and straying too far from its mission.Doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid vaccine in Kathmandu, Nepal.Narendra Shrestha/EPA, via ShutterstockIn a statement, the Gates Foundation said that it supported the work Gavi did with Covax. “As the pandemic evolved and with hundreds of millions of lives still at risk, Gavi’s board and other supporting Covax partners had to make supply and resource mobilization decisions quickly to respond to the unfolding crisis,” a foundation spokesperson said. “These decisions were not easy and involved vigorous dialogue among Gavi and its partners and supporters, including the foundation,” the spokesperson added.Covax has had to renegotiate its contracts with four suppliers of vaccines, to reduce them by between 400 and 600 million doses. Four hundred million doses from Pfizer that were coming as a donation from the United States government have been converted into future options available in 2023.“We did not massively overbuy,” Dr. Berkley said, adding that he expected the demand by countries that continue to try to do primary or booster dose delivery would largely align with the doses Gavi has available. “In a pandemic, I would want to err on the side of buying too many doses, rather than err on the side of not having enough doses, particularly given the fact that countries felt that there weren’t enough doses at the beginning,” he said. “If you want to get doses at the beginning, you’ve got to go ahead and put orders in, even if you don’t know if they’re going to work, and that’s risk. You have to have risk.”The Gavi secretariat is proposing to board members that the organization keep a pool of $1.8 billion that will allow for the acquisition of new doses as required into 2025 and support for the delivery of vaccines.Dr. Berkley said the “pandemic preparedness pool” is meant to act as insurance against another situation where Gavi needs to procure vaccines for developing countries (against a new Covid variant, for example) and is forced to compete with the deep pockets of richer nations. Some board members expressed concern at the idea of the organization sitting on these funds.“We just want to make sure the money is not used until we have a lot more conversations about where we want those funds to go,” one board member said. “We don’t have governance in place right now for how to manage that fund. The important thing is, we don’t want them to use these funds to broaden their mandate.”Dr. Orin Levine, an epidemiologist who until September 2021 represented the Gates Foundation on the Gavi board, said Covax’s fate was sealed by mid- 2021. “The fact that they were zero on the doses delivered in that period, near zero, is a fundamental blemish for us as a global community,” he said. “We couldn’t get any rich countries to slow down their individual vaccination order to help other people get started on their first ones.”

Read more →