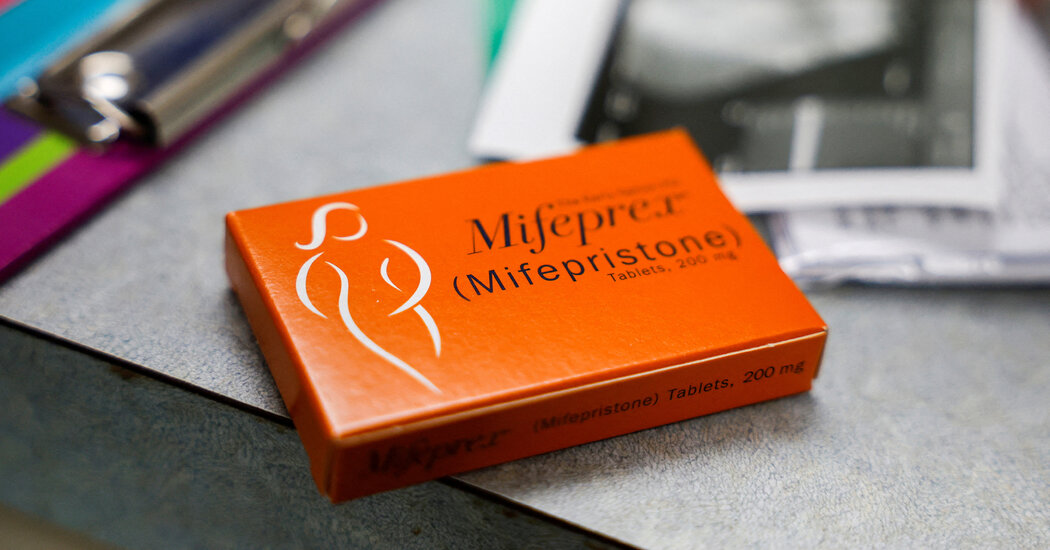

The NewsTens of thousands of women who are not pregnant are ordering abortion pills just in case they might need them someday, especially in states where access is threatened, according to a study published on Tuesday.After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, more women began ordering abortion pills just in case they became pregnant, especially in states where abortion access was under threat.Evelyn Hockstein/ReutersWhy It MattersThe practice, known as advance provision, is relatively new and has increased significantly since the Supreme Court’s decision in 2022 to overturn the national right to abortion.In the study, published in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers evaluated data from Aid Access, a telehealth organization that has long provided abortion pills to women in the first 13 weeks of pregnancy and began offering the medication to women in the United States who weren’t pregnant in September 2021.Before May 2022, when a draft of the Supreme Court decision was leaked, Aid Access had received about 6,000 advance provision requests, averaging 25 per day. Since then, it has received over 42,000 requests, averaging 118 per day, said Dr. Abigail Aiken, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin and a co-author of the study.The biggest spikes in demand followed events that raised doubts about the future availability of abortion. Requests peaked in the weeks between the leak and the Supreme Court’s decision in June 2022, and in April 2023 after a flurry of court rulings in a lawsuit by abortion opponents seeking to curtail mifepristone, a key abortion pill, a case now before the Supreme Court.Rates of requests were highest in states where abortion bans were expected — even higher than in states that already had bans. Asked why they requested the pills, most women said to “ensure personal health and choice” and “prepare for possible abortion restrictions,” according to the study.“People were obviously paying attention and seeing the threat of abortion access either going away or being reduced where they were and thinking, ‘I need to get prepared for that,’” Dr. Aiken said.Behind the NumbersData from September 2021 through April 2023 showed 48,404 advance provision requests and 147,112 requests from women seeking to terminate existing pregnancies. (Women in both categories completed telehealth consultations and Aid Access evaluated their medical information before prescribing pills.)Advance provision requesters were more likely than those already pregnant to be 30 or older, white and childless, and to live in urban neighborhoods with lower poverty rates than the national average. That might be partly because Aid Access offers free or reduced-price services to pregnant patients who need financial assistance, while advance provision requesters were expected to pay the full $110 cost, Dr. Aiken said.And because few organizations offer advance provision, women from marginalized or lower-income communities might be less aware “that it’s even a thing you can do,” she said.Medication abortion typically involves two pills: mifepristone, which has a shelf life of three to five years, followed a day or two later by misoprostol, which has a shelf life of 18 to 24 months.Dr. Aiken said a subset of advance provision requesters — 937 women, two-thirds of them in states with abortion bans or restrictions — answered follow-up questions. Most still had the pills, but 58 had taken them and 55 had given them to someone else.About 60 percent took the pills before seven weeks of pregnancy, early in the recommended time frame. A vast majority reported having enough information, including about expected bleeding and cramping. All 58 said the pills worked. Five visited health care providers afterward, but none went to the hospital or had serious complications.Larger ImplicationsLegal scholars say advance provision may be legal in some states with abortion bans. “Many state abortion laws require a provider to know a person is pregnant,” three law professors — David S. Cohen, Greer Donley and Rachel Rebouché — wrote in an article to be published in the Stanford Law Review. However, they added, in some states, abortion providers might be legally vulnerable since they know that “the pills are prescribed to terminate a future pregnancy.”Abortion opponents object to advance provision and claim abortion medication is dangerous. Abortion rights supporters say prescribing it in case of future need, like antibiotics for traveler’s diarrhea, increases access and underscores that the pills are safe, as many studies show.

Read more →