James F. Fries, Who Studied the Good Life and How to Live It, Dies at 83

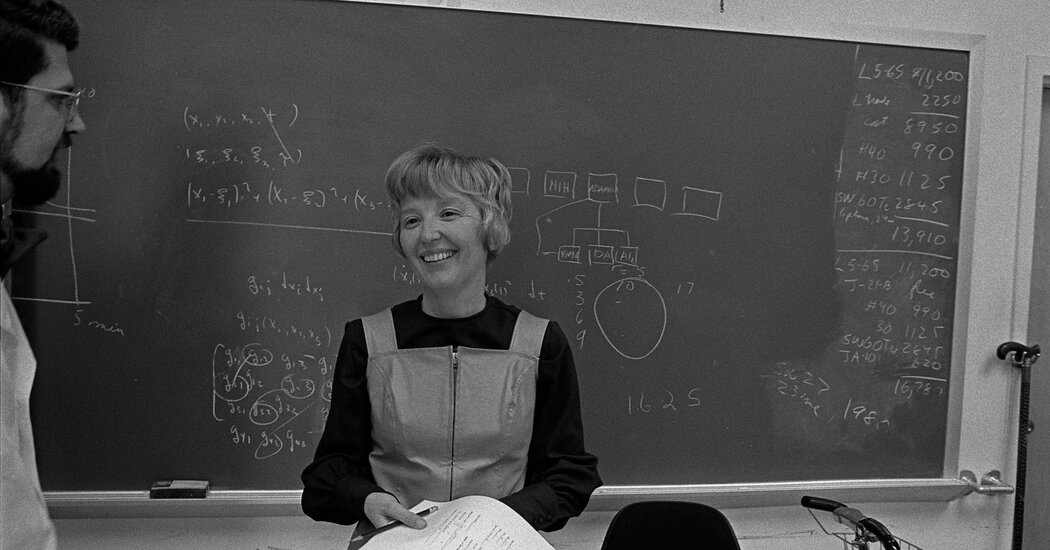

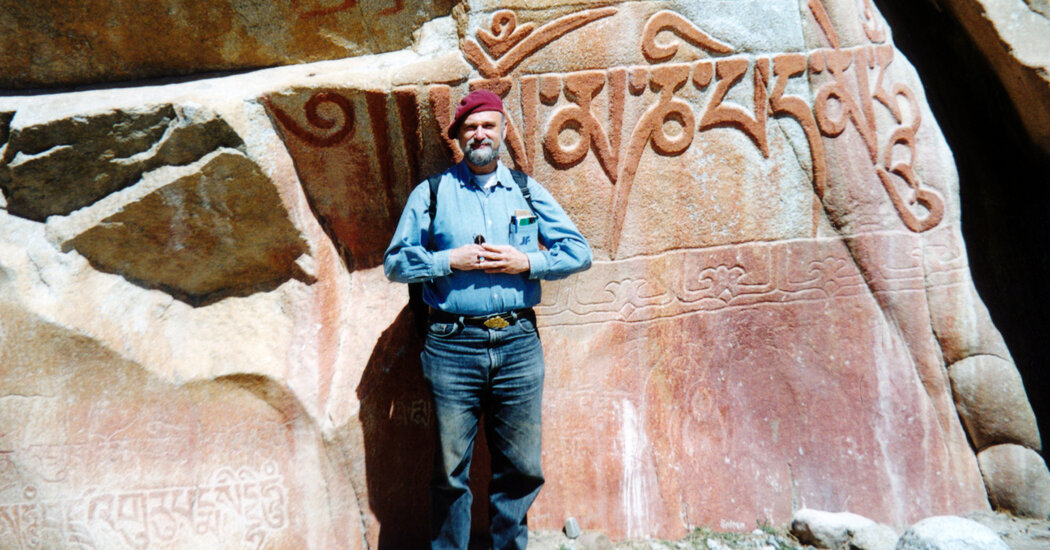

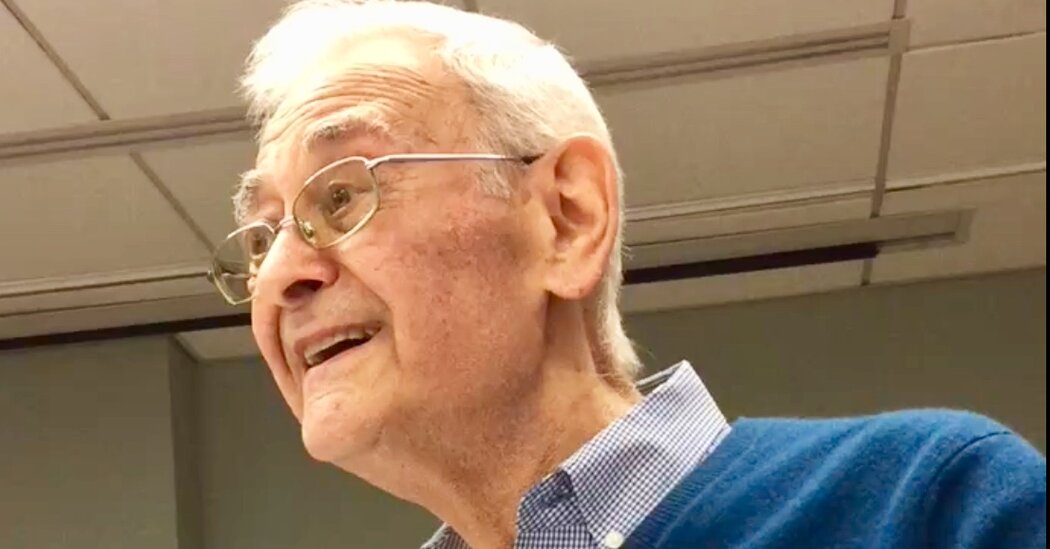

He showed that while a healthy lifestyle won’t help us live much longer, it can stave off chronic disease and disability until our final years.James F. Fries majored in philosophy as an undergraduate, so it’s no surprise that as a medical researcher he was obsessed with how to lead a good life, even though his interest was more about physical than moral well-being.His focus, starting in the mid-1970s, was on what Dr. Fries (pronounced freeze) and other scientists called the failure of success. They noted that one great achievement of the 20th century was the rapid increase in life expectancy, thanks to improvements in vaccinations and sanitation that dramatically reduced deaths from acute, transmissible disease.But that increase in life span did not mean an accompanying increase in “healthspan,” or the duration of one’s life free from chronic conditions like hypertension, diabetes and heart disease.Dr. Fries, who trained as a rheumatologist and spent his entire teaching career at Stanford University, was a data guy, long before large data sets became a common tool in medical research. He was among the first to create an international database of patients that tracked their health over time, an enormous effort that began in 1975 with a grant from the National Institutes of Health.“He was thinking about electronic health records and data mining in the 1970s,” Michael Joyner, a physiologist at the Mayo Clinic, said in a phone interview. “I wouldn’t call him an early adopter. I would call him a pioneer.”Early on, Dr. Fries noticed something strange in the numbers: While the average life span of patients didn’t change much depending on their lifestyle, the rates of morbidity — that is, affliction by chronic disease and disability — varied greatly between those who exercised and ate a healthy diet and those who smoked, overate and exercised infrequently, if at all.Put differently, exercise and a healthy diet don’t help you live longer, but they can help you postpone the onset of debilitating disease until close to the end of your life, a phenomenon that Dr. Fries called “compression of morbidity.”He died at 83 on Nov. 7 at an assisted living home in Boulder, Colo. His son, Greg, said the death, which was not widely reported at the time, was attributed to end-stage dementia.Dr. Fries outlined his compression of morbidity hypothesis in an article in The New England Journal of Medicine in 1980, then spent the rest of his career trying to prove it, using longitudinal studies of both large groups of people and so-called natural experiments, like a runners’ club, as measured against a control population.He practiced what he preached. In high school he ran the mile and pole-vaulted; as an adult, he took up jogging, running an average of 500 miles a year. An avid outdoorsman, he climbed the highest peaks on six continents, though at Mount Everest he had to turn back when a snowstorm endangered his crew just 3,000 feet from the summit.Dr. Fries was not without his critics. Some pushed back against his assumption that there was a limit to human beings’ natural maximum life span; others insisted that chronic disease was here to stay, and that lifestyle choices mattered little in the grand scheme of things.But he said he had the data to support his claims, and over time his core insight became a cornerstone of a new approach to healthy living, one that spilled out of the medical laboratory and into the pages of countless self-help books. Dr. Fries was the author of some himself; one, “Take Care of Yourself” (1979), which he wrote with Dr. Donald M. Vickery, has sold some 20 million copies.Another of his books, “Taking Care of Your Child” (1977), briefly made headlines in 1992. After an insurance provider announced that it would distribute copies to some 275,000 federal workers, President George Bush’s administration insisted that a chapter on contraception be removed lest it offend some parents.Dr. Fries took his approach to healthy living out of the laboratory and into the pages of self-help books, including this one from 1979, written with a colleague. It has sold some 20 million copies.Dr. Fries was careful to insist that the compression of morbidity was not inevitable, and he urged policymakers to develop tools to encourage healthy living and to make it easier for people to pursue interventions like statins and joint-replacement surgery, to help them stave off chronic disease and disability.But, ever the philosopher, he also recognized that staving off morbidity was ultimately a personal choice, and those who failed to follow his advice would have to live with the results.“Anguish arising from the inescapability of personal choice and the inability to avoid personal consequences may become a problem for many,” he wrote in a 2011 paper. “For others, exhilaration may come from recognizing that the goal of a vigorous long life may be an attainable one.”James Franklin Fries was born on Aug. 25, 1938, in Normal, Ill., the son of Albert and Orpha (Hair) Fries. His mother taught middle school English, and his father was a college business professor. The family soon moved to Evanston, Ill., where Albert Fries taught at Northwestern University, and then to California, where he taught at several institutions, including the University of Southern California.Jim Fries attended Stanford University and graduated with a degree in philosophy in 1960, the same year he married Sarah Tilden, whom he had met in a freshman history course.Weeks after their wedding ceremony, the Frieses drove east to Baltimore, where Dr. Fries attended medical school at Johns Hopkins University. He graduated in 1964 and stayed another four years as a resident before returning to Stanford, where he joined the faculty.His daughter, Elizabeth, died of breast cancer in 2005, the same year that his wife developed metastatic melanoma. She survived, but the disease left her disabled. Dr. Fries insisted that she remain active, and the two continued to travel extensively, taking cruises and walking tours around the world. At one point he carried her across a bridge in the Himalayas.Mrs. Fries died in 2017. Along with his son, Dr. Fries is survived by his brother, Ken, and five grandchildren.Dr. Fries retired in 2017, after his wife’s death and after he suffered a debilitating stroke. A few months later, he moved to Colorado to be near his son.

Read more →