Diane Coleman, 71, Dies; Fiercely Opposed the Right-to-Die Movement

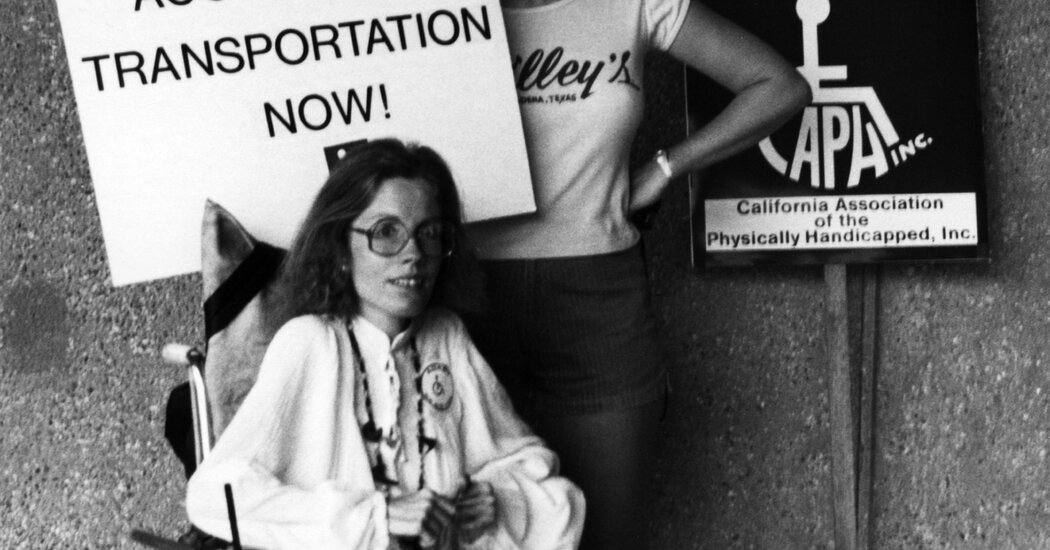

Her fight for disability rights included founding a group called Not Dead Yet, which protested the work of Dr. Jack Kevorkian and others.Diane Coleman, a fierce advocate for disability rights who took on Dr. Jack Kevorkian, the right-to-die movement and the U.S. health care system, which she charged was responsible for devaluing the lives of Americans like her with physical and mental impairments, died on Nov. 1 at her home in Rochester, N.Y. She was 71.Her sister Catherine Morrison said the cause was sepsis.Ms. Coleman was born with muscular spinal atrophy, a disorder that affected her motor neurons. She was using a wheelchair by 11, and doctors expected her to die before adulthood.Instead she blossomed, graduating as valedictorian from her high school and receiving a joint J.D.-M.B.A. from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1981.It was only after several years of working as a consumer protection lawyer that she shifted her energies to disability rights, joining a flourishing movement that was pushing for anti-discrimination laws at every level of government, including improvements on transit and in buildings.Ms. Coleman was a member of Adapt, considered one of the most militant disability rights groups. She participated in scores of protests, blocking the entrances to buildings where conferences were held or government offices were housed, and she was arrested more than 25 times.Ms. Coleman, center, in 1988 at one of the numerous protests in which she participated. She was arrested more than 25 times.Tom OlinWe are having trouble retrieving the article content.Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.Thank you for your patience while we verify access.Already a subscriber? Log in.Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Read more →