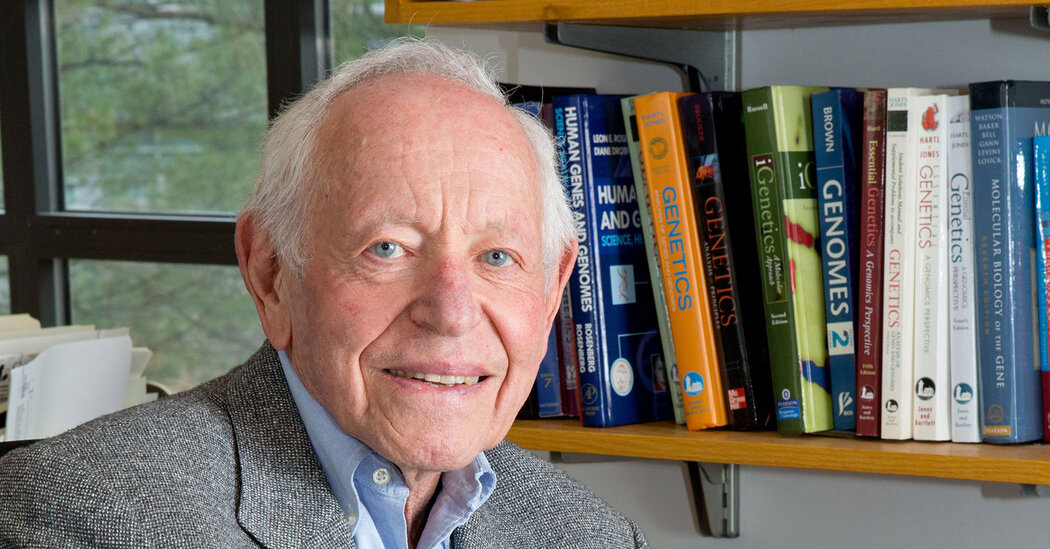

Leon E. Rosenberg, Geneticist Who Wrote of His Depression, Dies at 89

After years of pioneering research into inherited disorders, mostly in children, he spoke openly about his struggle with mental illness.Dr. Leon E. Rosenberg, who after spending decades as a pioneer in the field of medical genetics revealed that he had spent just as long struggling with manic depression, and who then urged doctors to be more open about their own mental health, died on July 22 at his home in Lawrenceville, N.J. He was 89.His wife, Diane Drobnis Rosenberg, said the cause was pneumonia.Dr. Rosenberg straddled the worlds of clinical and laboratory medicine. He labeled himself a “physician-scientist” whose research methods began and ended at the bedside of a patient with an undiagnosed condition, which he then tried to define and treat.Beginning in the early 1960s, he specialized in inherited metabolic disorders — cases in which the body is unable to process certain compounds, which then accumulate and poison a patient.Most of his patients were children, including one of his first, a 9-year-old boy named Steven, whose skeletal muscles were rapidly wasting away. Dr. Rosenberg, who was then a fellow at the National Institutes of Health, found nothing wrong except a high level of amino acids in Steven’s urine. He interviewed Steven’s parents, who said they had had two other children with similar conditions, both of whom had died. Steven died not long after.“I was unable to change the course of Steven’s illness,” Dr. Rosenberg wrote in a 2014 article. “But he changed the course of my professional life. He showed me that asking research questions based on seeing patients was like medical detective work. Even more important, he ignited my interest in genetic disorders and kindled it.”Dr. Rosenberg moved to the Yale School of Medicine in 1965, intent on solving mysteries like Steven’s — which he did, many times over. He was the founding chairman of the school’s department of human genetics and, later, the school’s president.He scaled the peaks of his profession, sitting on corporate boards and joining the National Academy of Sciences. In 1989 he was shortlisted to run the National Institutes of Health, alongside Dr. Anthony Fauci.But, as Dr. Rosenberg revealed much later, Steven’s case also came not long after his own first episode of crippling depression, what he called his “unwanted guest.” His first months at the National Institutes of Health had been difficult; he felt like a failure and wanted to leave research entirely.Though similar episodes struck later, often around major career changes, he never talked about them, or sought treatment, until he attempted suicide in 1998. His doctor diagnosed bipolar II disorder, and Dr. Rosenberg underwent electroshock therapy and took lithium.Doctors can suffer from depression just like anyone else, but Dr. Rosenberg was the rare physician who spoke openly about it — first in classroom and professional lectures, then in a series of articles and, ultimately, in a book, “Genes, Medicines, Moods: A Memoir of Success and Struggle” (2020).“I am proof,” Dr. Rosenberg wrote in his memoir, “that it is possible to live a highly successful career in medicine and science, and to struggle with a complex, serious mental illness at the same time.”He called on his fellow doctors to speak up as well, both for their own sake and for the sake of their families, colleagues and patients.“The list of writers who have described their suicidal attempts and suicidal thoughts is long and illustrious,” he wrote in a 2002 article. “Yet physicians and scientists, who commit and attempt suicide at least as often as artists, writers, politicians and business leaders, have been remarkably silent.”Several of Dr. Rosenberg’s relatives had similarly suffered from mental illness, and he marveled at the coincidence that his professional career and personal struggles both revolved around inherited disorders.“I am proof,” he wrote in his memoir, “that it is possible to live a highly successful career in medicine and science, and to struggle with a complex, serious mental illness at the same time.”Leon Emanuel Rosenberg was born on March 3, 1933, in Madison, Wis. Both his parents, Abraham and Celia (Mazursky) Rosenberg, had fled pogroms in present-day Belarus, though they did not meet until they settled in Waunakee, a Madison suburb.After working for a while as a peddler, Abraham made enough money to open his own general store. He learned English quickly and even perfected a rural Wisconsin accent, which helped him relate to his customers. Celia, a homemaker, maintained her thick Yiddish accent.A childhood accident involving a mill at Celia’s family farm had mutilated her left hand, leaving all but her thumb and forefinger useless. “Sometime around age 5,” Dr. Rosenberg wrote in his memoir, “while holding her left hand in both of mine, I told her that I intended to be a doctor so I could repair her hand.”Leon was an exemplary student: He was valedictorian of his high school and finished summa cum laude at the University of Wisconsin, where he graduated in 1954 and received his medical degree in 1957. He interned at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital before moving to the National Institutes of Health as a research fellow in 1959.His first marriage, to Elaine Lewis, ended in divorce. Along with his wife, he is survived by his brother, Irwin, the former dean of the School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University; his sons, Robert Rosenberg and David Korish; his daughters, Diana Clark and Alexa Rosenberg; six grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.It was while at Yale that Dr. Rosenberg led research into inherited metabolic disorders, despite skepticism from colleagues about the very basis of such work. “Don’t be silly,” he recalled one Yale nephrologist telling him. “There is no such thing.”Dr. Rosenberg proved him wrong. He filled lectures with case studies of children — Steven, of course, followed by Dana, Lorraine, Robby and others — who presented inexplicable disorders, which he repeatedly showed to be caused by their bodies’ inability to metabolize various acids, and which could often be easily treated.His research brought him public prominence, both as a researcher and as an advocate for equity in medicine. As the dean of the Yale School of Medicine from 1984 to 1991, he made it easier for people of color and women to rise to senior faculty positions, and he placed students as volunteers in New Haven public schools.He left Yale in 1991 to become the chief science officer at Bristol Myers Squibb. In 1998 he moved to Princeton University as a lecturer in molecular biology, with a joint appointment, also as a lecturer, in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs (now the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs).Dr. Rosenberg made national headlines in 1981 when he testified before a Senate subcommittee on a bill that would define life as beginning at conception, in effect overturning Roe v. Wade. Of the eight doctors invited to speak, he was the only one to disagree with the bill’s premise — and he said so forcefully.“Don’t ask science or medicine to help justify that course, because they cannot,” he said. “Ask your conscience, your minister, your priest, your rabbi, or even your god, because it is in their domain that this matter resides.”The bill failed soon after.

Read more →