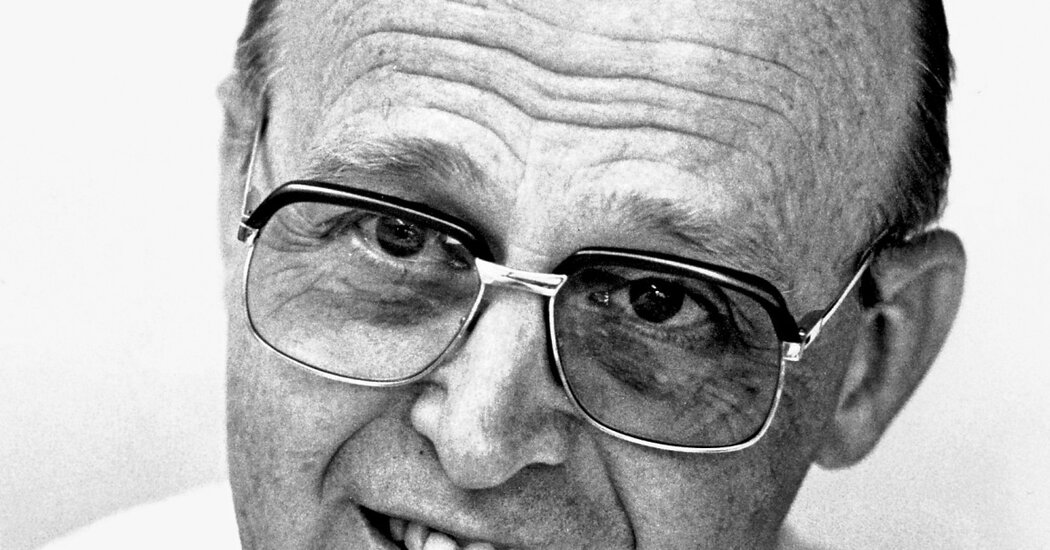

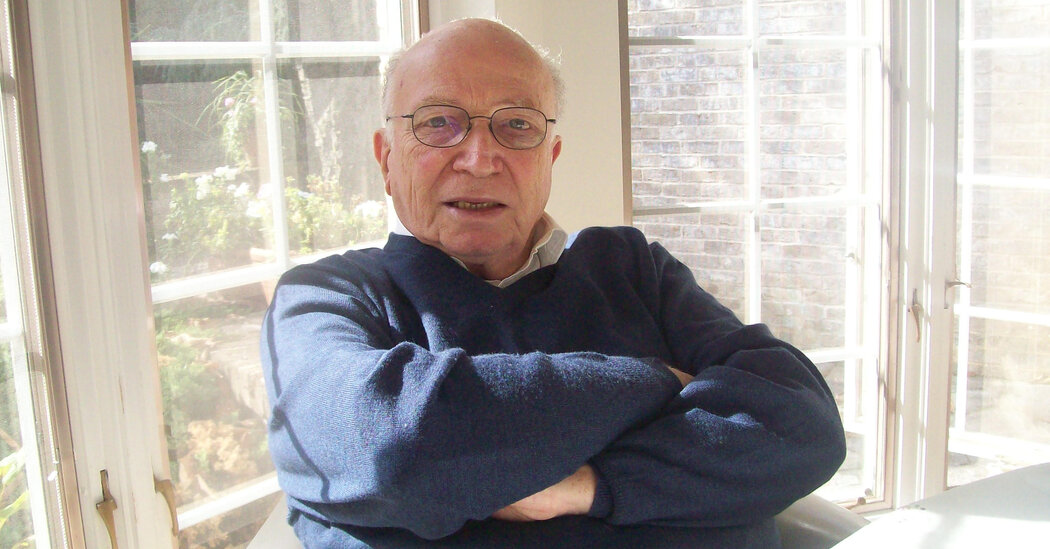

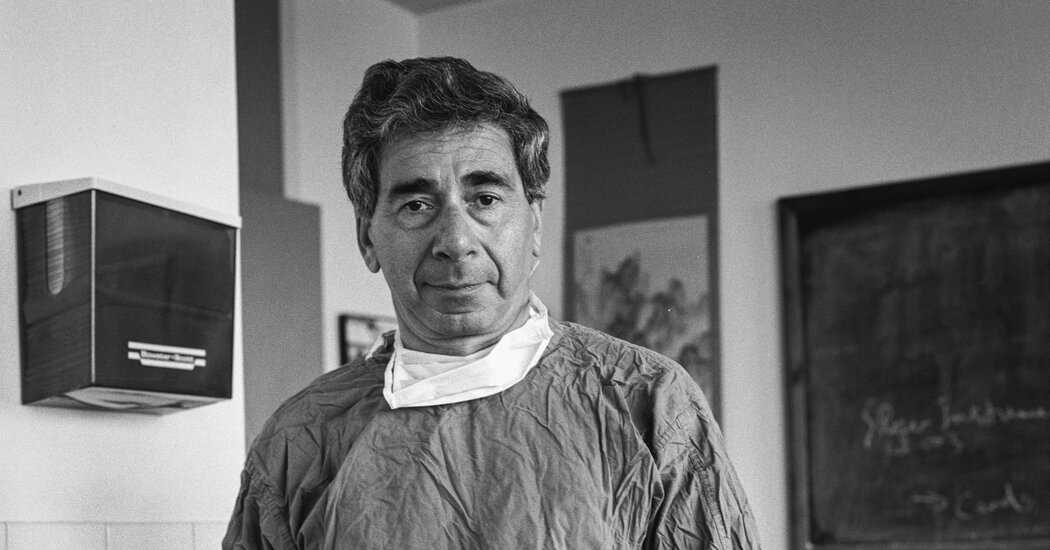

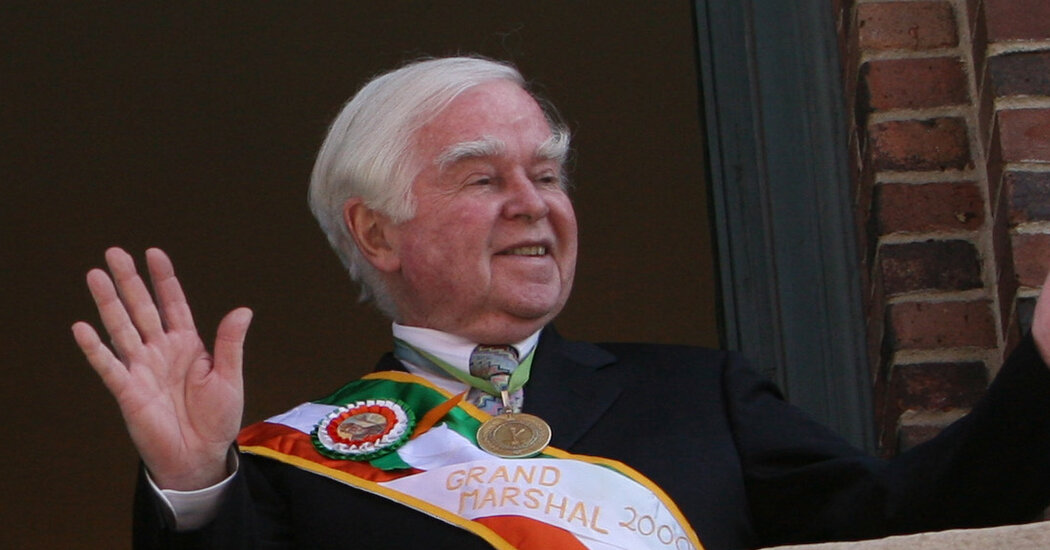

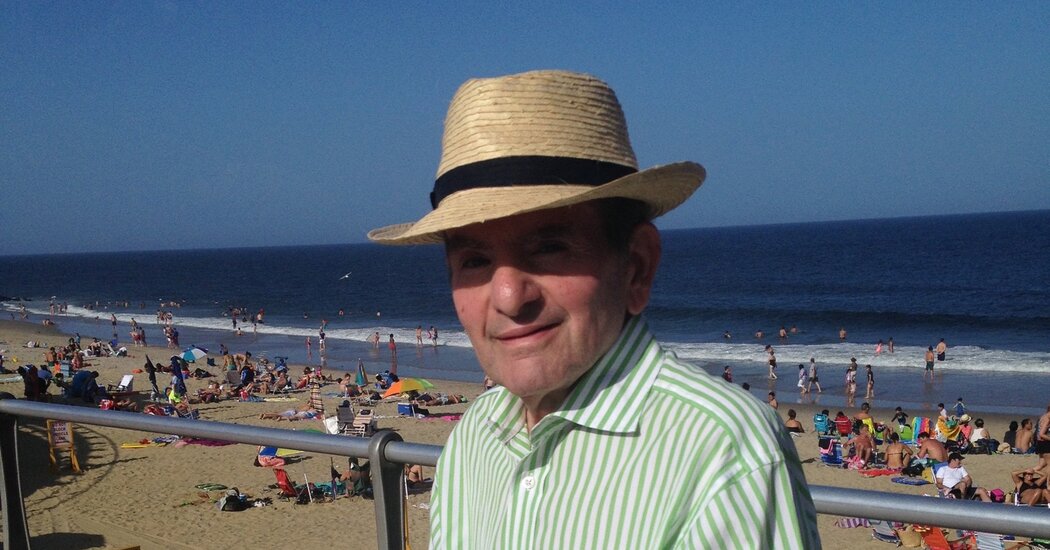

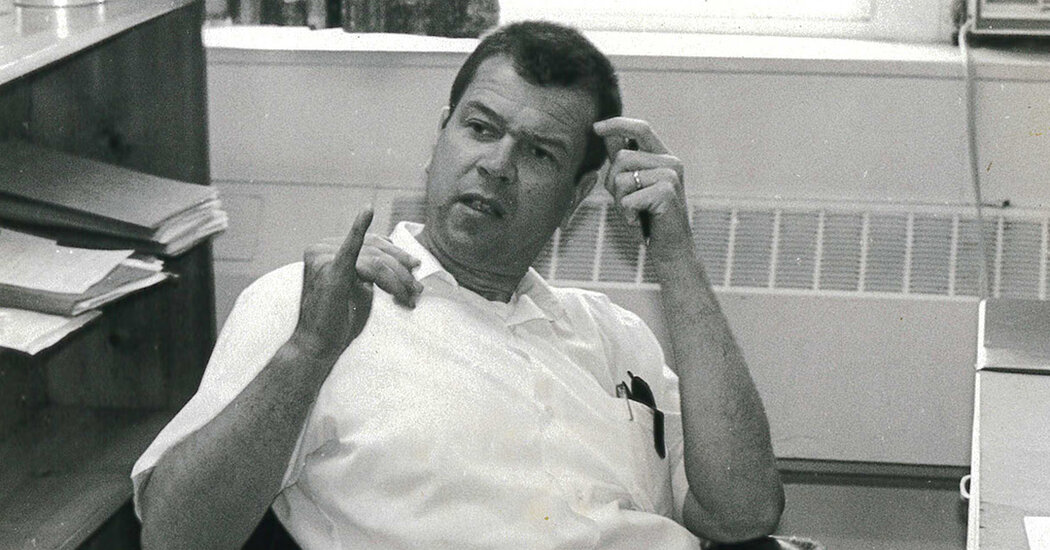

He treated celebrities, advised a governor and saved an Irish historical society. But he died under a cloud of sexual assault allegations.Kevin M. Cahill, who managed to pack several careers into a single life as a leading expert on tropical diseases, a doctor to celebrities and politicians, a close adviser to Gov. Hugh L. Carey of New York and a savior to the ailing American Irish Historical Society, but who later faced allegations of sexual assault by two women, died on Wednesday at his home in Point Lookout, N.Y., on Long Island. He was 86.His son Brendan said that the cause of death had not been determined, but that his father had been in failing health.A short, stocky man with big, bushy eyebrows and an accent that tilted between Gaelic brogue and Noo Yawkese, Dr. Cahill managed to become a globe-trotting humanitarian while keeping thick roots planted in New York’s Irish American community.After an early stint as a doctor in Cairo and India, where he worked alongside Mother Teresa, Dr. Cahill returned to New York, where he established one of the country’s first centers for tropical disease, at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan. He was among the first doctors to call attention to the city’s emerging AIDS crisis, organizing a groundbreaking conference on the disease in 1983.He spent the late 1970s commuting to Albany, where, as Governor Carey’s health policy expert, he moved mountains to reshape the state’s flailing medical bureaucracy, making a host of enemies but impressing even his detractors as a quick study and an effective political infighter.A top expert in humanitarian medicine who worked in 65 countries, Dr. Cahill established an amputee clinic in Somalia and directed earthquake relief in Nicaragua, experiences he discussed in 1993 on the NPR program “Fresh Air With Terry Gross.”He was the personal physician to a long list of elite New Yorkers, including the top figures in the city’s Roman Catholic hierarchy. He was with Leonard Bernstein when Bernstein took his last breath. He was one of two American doctors invited to Rome to assess the health of Pope John Paul II after he was shot in 1981.And as a prominent figure among Irish Americans who quoted Yeats with ease, he revived the American Irish Historical Society, which was founded in 1897 and occupies a stately former townhouse on Fifth Avenue, across from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.The society had practically ceased to exist when Dr. Cahill took it over in the early 1970s. He raised funds to renovate its home and made its annual gala a must-do on the city’s social calendar, in the process helping to make Ireland a subject of popular fascination.“Dr. Cahill was a pioneer in bringing a prominence and seriousness to the study of Irish and Irish American culture that had long been lacking,” Peter Quinn, a writer and former member of the historical society’s board, said in a phone interview.Dr. Cahill’s life was not without controversy. His critics found him self-serious, nepotistic and egotistic.As his time as the head of the American Irish Historical Society wore on, he was accused of treating it more and more like his personal kingdom. He installed his sons as officers, booted officials who crossed him and unilaterally announced a plan to sell the townhouse in 2021, a move that has been under review by the state government.“The building on Fifth Avenue is something that stands for all of us,” Brian McCabe, a former leading figure in the society, told The New York Times that year. “This is about a very small group controlling what is held in trust for the Irish in America and around the world.”In 2020 a former patient, Megan Wesko, sued Dr. Cahill in federal court, alleging that he had pursued a romantic relationship with her and sexually assaulted her during an examination, a development reported in The Times in June. In 2022 another woman, Natalie Mauro, said that he had also sexually assaulted her at his office.Dr. Cahill was not charged with any crimes. He denied the allegations, and the lawsuit was still pending at his death.Dr. Cahill, left, with Cardinal Francis Spellman at the Tropical Disease Research Center of St. Clare’s Hospital in Manhattan in 1966. Dr. Cahill was the personal physician to a long list of elite New Yorkers, including the top figures in the city’s Roman Catholic hierarchy.Meyer Liebowitz/The New York TimesA grandson of Irish immigrants, Kevin Michael Cahill was born on May 5, 1936, in the Bronx. His father, John, was a doctor. His mother, Genevieve (Campion) Cahill, was a teacher and homemaker.He studied classics at Fordham University, graduating in 1957, and received his medical degree from Cornell in 1961. As a medical student, and later as a fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, he traveled to Calcutta, India (now Kolkata), where he worked in a local clinic alongside Mother Teresa, then a little-known Albanian nun.“I find romance in settings that others might — quite legitimately — see only as dirty, broken-down wastelands,” he said in a graduation address at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts in 2008. “Surely those negatives existed in Calcutta. But amidst the fetid stenches of Indian urban decay, I mainly recall the strong aroma of exotic spices.”He served in the Navy Medical Corps from 1963 to 1965, working at a research facility in Cairo, after which he returned to New York to establish his medical practice.He married Kathryn McGinity in 1961. She died in 2004. Along with his son Brendan, he is survived by four other sons, Christopher, Kevin, Sean and Denis, and nine grandchildren.Dr. Cahill’s experience made him an obvious choice by Lenox Hill Hospital to lead its Tropical Disease Center, which opened in 1966. In 1970 he was named chairman of the department of tropical diseases at the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin, a post he held until 2006.After he became governor in 1975, Mr. Carey, himself a product of New York City’s Irish Catholic political scene, took Dr. Cahill with him to Albany and gave him the task of cleaning up the state’s sprawling, nearly insolvent health care system.The two were old friends, and Dr. Cahill served as one of the governor’s closest advisers. He worked for $1 a day, one day a week, often staying overnight at the governor’s mansion.“He’s very single‐minded, quite stubborn and rigid,” Albert H. Blumenthal, a Democrat who served as majority leader in the State Assembly, told The Times in 1977. “but he’s an easy man to deal with. There’s no deceit to him.”The relationship didn’t last, though; Dr. Cahill and Mr. Carey reportedly had a falling-out, and Dr. Cahill left the governor’s office in 1980.He went on to work for the New York City Board of Health, advise the United Nations on global health and direct the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs at Fordham. He also wrote several books, including, most recently, “Tropical Medicine: A Clinical Text” (2021). He left both Fordham and Lenox Hill Hospital in 2020.

Read more →