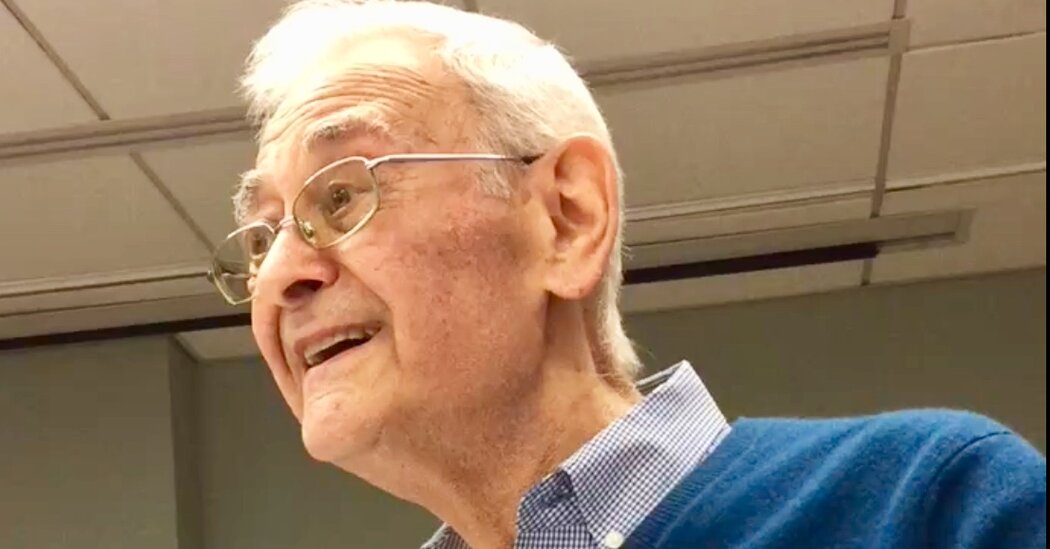

Yehuda Ben-Yishay, Pioneer in Treating Brain Injuries, Dies at 88

After working with wounded Israeli soldiers in the 1970s, he developed a holistic approach to helping patients regain some semblance of the life they had before.Yehuda Ben-Yishay, a psychologist whose experience working with wounded Israeli soldiers led him to make pioneering advances in treating traumatic brain injuries, helping countless patients return to some semblance of the life they had before, died on March 24 at the NYU Langone Health hospital in Manhattan. He was 88.His death was confirmed by his wife, Myrna Ben-Yishay, a genetic counselor.Before Dr. Ben-Yishay developed what he called holistic cognitive therapy in the 1970s, most scientists thought that the adult brain was immutable, and that serious injuries — and the behavioral changes that resulted — were permanent.Working with Leonard Diller, his colleague at Rusk Rehabilitation at NYU Langone Health, Dr. Ben-Yishay proved otherwise, setting aside the biology of the brain to show that things like attention, memory and behavior could still be strengthened, or compensated for, in recovering patients.The two first demonstrated their ideas in Israel, where hundreds of soldiers, many of them tank drivers, had suffered traumatic brain injuries in the sprawling tank battles across the Sinai Desert and in the Golan Heights during the Yom Kippur War in 1973.They engaged about a dozen patients in what Dr. Ben-Yishai described as a therapeutic milieu. It wasn’t enough for a doctor to work one-on-one with a patient; everyone from nurses to families to other patients had to be involved in creating a safe environment in which a patient could address a brain injury and its consequences and start to regain or compensate for damaged cognitive skills.The two doctors returned to New York and in 1978 Dr. Ben-Yishay put their experience into practice with the NYU Rusk Holistic Day Program. A talented storyteller with a flair for drama, he was renowned for his ability to engage with patients, and he personally treated hundreds over the next four decades.“The scientific community’s work is irrelevant to what goes on here,” he told The New York Times Magazine in 2000. “The rehabilitation of head-injured individuals is a clinical, creative endeavor. Can you really say how this blob of Jell-O creates all this wonderful feeling and thinking? No. The question really is, Can you reconstruct Humpty Dumpty after he has been shattered to pieces?”The process isn’t easy, or cheap. Dr. Ben-Yishay’s 20-week program involves daylong sessions, often in small groups, and costs about $60,000. Yet it has become the gold standard for treating brain injuries, inspiring similar programs worldwide.“I was giving a talk about my program in Amsterdam,” said Keith Cicerone, the retired director of cognitive rehabilitation at the JFK Medical Center in New Jersey. “Afterward, several people from around the world came up to me and said how similar their programs were. Pretty soon we realized that we had copied from Yehuda.”Yehuda Ben-Yishay was born on Feb. 11, 1933, in Cluj, a city in the Transylvania region of western Romania. His father, Chaim Ben-Yishay, was a businessman; his mother, Leah (Finkelstein) Ben-Yishay, was a seamstress.His family went through World War II largely unscathed. Though hundreds of thousands of fellow Romanian Jews died during the Holocaust, hundreds of thousands survived, especially those in the southern reaches of Transylvania, where the family had moved shortly before the war.The Ben-Yishays were eager Zionists, and in 1946 they boarded a converted cattle ship with about 2,000 other Jews bound for Palestine. The British authorities had banned such mass migration, and on arrival Yehuda he and his two brothers and sister were separated from their parents as they were placed in refugee camps.After Israel’s independence in 1948, Dr. Ben-Yishay served in the Nahal, a part of the Israel Defense Force that built agricultural settlements. He later attended Hebrew University in Jerusalem, hoping to study psychology, but there was no one to teach it: Arab guerrillas had murdered the head of the department and several colleagues in 1948.Dr. Ben-Yishay studied sociology instead, graduating in 1957. He won a scholarship to the New School for Social Research in Manhattan and arrived at the end of that year.To cover his living expenses, he taught Hebrew and worked with retirees, including at a summer camp in Brewster, N.Y. There he met Myrna Pitterman; they married in 1960 and had three sons, Ari, Ron and Seth. All survive him along with his brothers, Yisrael and Meir; his sister, Pnina; and eight grandchildren.At the New School, Dr. Ben-Yishay fell under the guidance of a German émigré psychologist named Kurt Goldstein. Dr. Goldstein insisted that patients with traumatic injuries could recover only in a “holistic” environment, which would take into account not only their physical well-being but also their emotional and spiritual health.Dr. Ben-Yishay joined the Rusk Institute in 1964 and received his Ph.D. in psychology from N.Y.U. three years later. The institute’s founder, Howard A. Rusk, was himself a pioneer in physical rehabilitation, and like Dr. Goldstein he believed in a “whole patient” approach. (He was also a medical columnist for The New York Times.)Dr. Rusk encouraged Dr. Ben-Yishay and Dr. Diller, who ran the psychology department at Rusk, to apply that same approach to brain injuries, an increasingly urgent field. Thanks to improvements in automobile safety and battlefield medicine, more people were surviving accidents and combat incidents but with significant, if not always obvious, damage to their brains.Dr. Ben-Yishay confronted what was then considered a philosophical question: What is the nature of recovery? Is it strictly neurological, a result of biological changes in the brain? Or is it also behavioral, psychological, a result of learning and outside intervention by doctors, friends and family?Most researchers assumed it was the former, and that little could be done, aside from isolated efforts to make life easier for patients whom they thought were destined to live a life of mental anguish. Dr. Ben-Yishay thought otherwise, that cognition — things like memory, attention, reasoning — could be relearned or strengthened after a brain injury, and he spent the better part of the 1970s developing his approach.Though he faced significant skepticism at first, his program showed results. Before he began, only about 20 percent of patients with traumatic brain injuries were able to go back to work in some capacity; about two-thirds of patients who worked with Dr. Ben-Yishay and his team could do so, he estimated.Dr. Ben-Yishay was always quick to note the limits to his program. He was not there to cure a patient; no one could.“Once brain-injured, you are always brain-injured, for the rest of your life,” he told The Times in 2006.What he could do, though, was help patients develop ways to compensate, which began with recognizing what had happened to them and committing to the hard work of building a new life. He used words like persistence and courage to describe the key to success in his program, and he helped his patients unlock those qualities within themselves.“If you are a sourpuss,” he liked to say, “you are not rehabilitated.”

Read more →