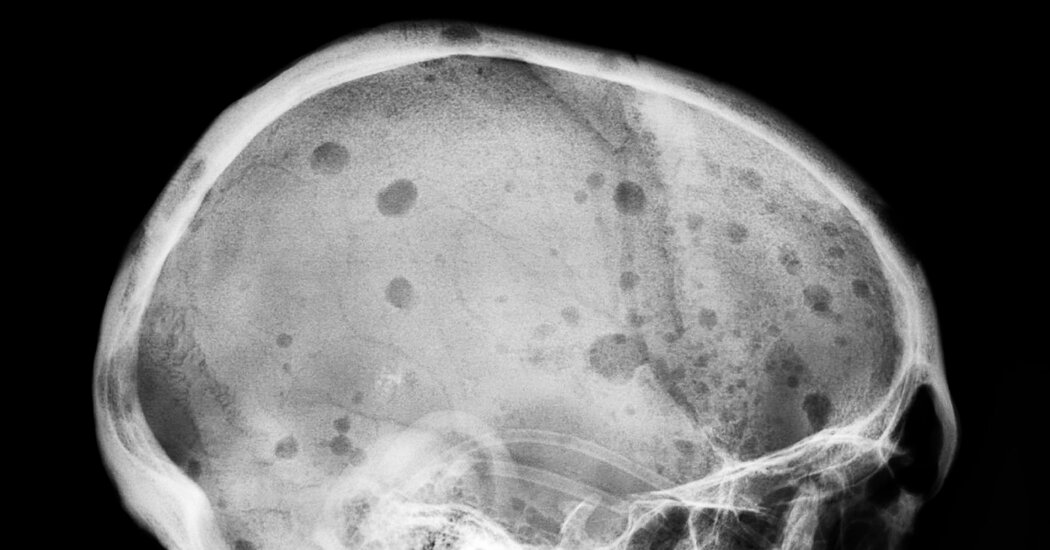

24 minutes agoShareSaveDominic HughesHealth CorrespondentAnnabel RackhamHealth ReporterShareSaveGetty ImagesNew cases of the sexually transmitted infection syphilis have risen again in England, continuing a trend dating back to the early 2000s.While the overall number of people diagnosed with gonorrhoea has fallen, there has been a significant increase in the number of cases where the infection is drug resistant, new UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) data shows. Health experts say this is a real concern, although the actual number of drug-resistant cases remains very low. The NHS recently announced the rollout of the world’s first vaccine programme to protect against gonorrhoea, aimed principally at gay and bisexual men.Overall, there were 9,535 diagnoses of what is described as early-stage syphilis in England in 2024, up 2% on 2023.But the overall figure for syphilis, including what is called late-stage syphilis, or complications from the infection, rose 5% to 13,030.The figures for gonorrhoea show a more complicated picture.Overall, 2024 saw a 16% fall in gonorrhoea cases, with 71,802 diagnoses compared to 85,370 in 2023, with the greatest fall among 15- to 24-year-olds. Giulia Habib Meriggi, a surveillance and prevention scientist for sexually transmitted infections at UKHSA, urged caution over the decline.”This is the first year in the last couple of years where [the numbers] have actually gone down,” she said.”It’s still the third highest number of cases we’ve had in a year in recorded history, so it is sort of good news but it doesn’t mean it will stay that way. “It is obviously really important for people to still get tested regularly and use condoms with new partners.”Drug resistant gonorrhoea on the riseBy contrast, there has been an acceleration in diagnoses of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea. Some strains of the bacteria which causes the disease no longer respond to the first-line treatment, the antibiotic ceftriaxone.The numbers themselves remain low, with 14 cases reported in the first five months of 2025, compared with 13 cases for the whole of 2024. But six of those 14 cases so far this year have been extensively drug-resistant, meaning they were resistant not just to ceftriaxone but also to second-line treatment options.Most of the ceftriaxone resistant cases were linked with travel to or from the Asia-Pacific region, where levels of ceftriaxone resistance are high.UKHSA scientist Prarthana Narayanan describes the trend as “worrying”.”The numbers are still small but the reason this is worrying is because, once resistance in gonorrhoea becomes endemic, then it becomes extremely hard to treat, because ceftriaxone is the last first-line therapy we have for it. “We want to make sure that the spread of resistant strains is reduced as much as possible to try and prolong how long we can use ceftriaxone to treat it for,” she said. What are the symptoms of syphilis and gonorrhoea?Syphilis can present as small sores or ulcers on and around the genitals, as well as white or grey warty growthsSores in other areas, including in your mouth or on your lips, hands or bottomA rash on the palms of your hands and soles of your feet that can sometimes spread all over your bodyWhite patches in your mouthFlu-like symptoms, such as a high temperature, headaches, tiredness and swollen glandsPatchy hair loss on the head, beard and eyebrowsGonorrhoea can cause fluid or discharge from the penis or vaginaA burning pain when you urinatePain in the lower abdomen (for women) or sore testiclesGrowing concern over drug resistanceNumbers of sexually transmitted infections remain high, warns UKHSA, with the impact felt felt mainly in 15- to 24-year-olds, gay and bisexual men and some minority ethnic groups. But the increase in drug resistant cases of gonorrhoea is a real concern, amid wider worries around the growth in antimicrobial resistance.The World Health Organisation describes antimicrobial resistance as an issue of global concern and one of the biggest threats to global health. It threatens our ability to treat common infections and to perform life-saving procedures, including chemotherapy for cancer, caesarean sections, hip replacements, organ transplants and other operations.This is why, even though only 14 cases of drug-resistant gonorrhoea were identified this year, health experts urge anyone having sex with new or casual partners to use a condom and get tested regularly, whatever their age or sexual orientation.

Read more →