Researchers see need for warnings about long-range wildfire smoke

Smoke from local wildfires can affect the health of Colorado residents, in addition to smoke from fires in forests as far away as California and the Pacific Northwest.

Researchers at Colorado State University, curious about the health effects from smoke from large wildfires across the Western United States, analyzed six years of hospitalization data and death records for the cities along the Front Range, which reaches deep into central Colorado from southern Wyoming.

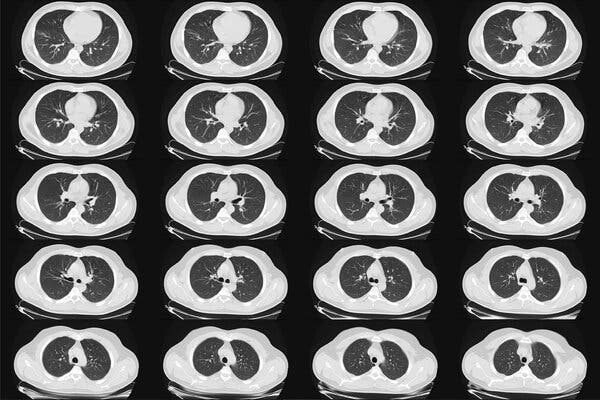

They found that wildfire smoke was associated with increased hospitalizations for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and some cardiovascular health outcomes. They also discovered that wildfire smoke was associated with deaths from asthma and cardiovascular disease, but that there was a difference in the effects of smoke from local fires and that from distant ones.

Long-range smoke was associated with expected increases in hospitalizations and increased risk of death from cardiovascular outcomes.

But when the research team separated out health effects of smoke from local wildfires in early summer 2012 from long-range smoke from late summer 2012 and summer 2015, they found that local wildfires were associated with meaningful decreases in hospitalizations, especially for asthma.

The study, “Differential Cardiopulmonary Health Impacts of Local and Long-Range Transport of Wildfire Smoke,” was recently published in GeoHealth, a journal from the American Geophysical Union.

advertisement

Residents protect themselves from local fires

Sheryl Magzamen, lead author of the study and an associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences at CSU, said the team believes that evacuation efforts and related media coverage of local wildfires may have helped protect residents from adverse health effects of smoke exposure as well as direct impacts of the fires.

“There’s a lack of communication about smoke from distant wildfires,” said Magzamen. “Generally when there are local fires, there are advisories in the news that are associated with evacuations and local fire conditions. Due to the presence of the fire, people take measures to protect themselves. This could be why we see this lower risk of health effects from smoke associated with local fires.”

Researchers described the long-range wildfire smoke as resembling fog, which is what Magzamen said she noticed in Fort Collins in August 2015. At the time, she was collaborating on a project with Jeff Pierce, associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science.

“I thought it was weird to see fog on that day,” she explained. “Jeff said, ‘That’s actually smoke.’ We all took a step back.”

Smoke changes with age

advertisement

Pierce, a co-author on this study, said researchers don’t really know how harmful smoke is as it gets older, or becomes long-range smoke.

“In Fort Collins, about half the time we had smoke in late August or September 2020, this was smoke from the Cameron Peak Fire,” he explained. “This smoke was only a couple hours old when it got here. At other times, we were getting smoke from California, and the smoke from the Cameron Peak Fire was either going over our heads or further south.”

The Cameron Peak Fire was reported on Aug. 13, 2020, and burned into October, consuming 208,913 acres on the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests in Larimer and Jackson Counties and Rocky Mountain National Park. It was the first wildfire in Colorado history to burn more than 200,000 acres.

The average person would not notice a difference in wildfire smoke, Pierce said.

“If the smoke is even two days old, things happen chemically, which changes the smoke a lot,” he explained. “If it didn’t smell like wood burning, it was long-range smoke from California.”

Magzamen said that the team is working to better understand these chemical changes.

“As the small particles found in wildfire smoke age, they can cause more oxidative stress and more respiratory health effects,” she said. “But wildfire smoke itself is a mixture of particles and gases. Teasing apart the effects of all the components of smoke and what happens to the mixture across space and time — and how those changes impact health — is an enormous scientific challenge.”

Better air quality monitoring

Magzamen said the gap in understanding the source of wildfire smoke is because it historically has been measured by land-based sensors, which are primarily located in large urban areas and sparsely located in other regions, even along the Front Range.

“Even over the last five years, our air quality monitoring networks have been enhanced with new technologies and better measurements of real-time smoke effects,” she said.

CSU researchers are now collaborating with local government officials on messaging related to the different types of wildfire smoke, with a specific aim to reach the most vulnerable populations. This includes caretakers of young children, people experiencing homelessness and others who can’t shelter safely in place during wildfire season.

“We want people to be smoke-aware,” she said. “On the Front Range, we have wildfire smoke every summer. We may not get Cameron Peak-size type of fires every year, but we are downwind for pretty much the entire Western United States,” she said. “It’s critical that we keep people healthy and safe.”