Plan to Ditch the Mask After Vaccination? Not So Fast.

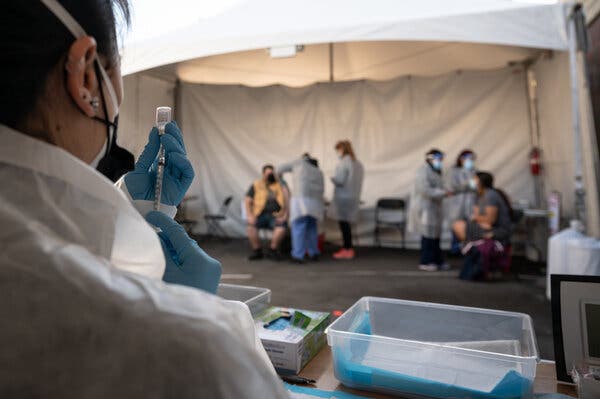

#masthead-section-label, #masthead-bar-one { display: none }The Coronavirus OutbreakliveLatest UpdatesMaps and CasesRisk Near YouVaccine RolloutNew Variants TrackerAdvertisementContinue reading the main storySupported byContinue reading the main storyPlan to Ditch the Mask After Vaccination? Not So Fast.It’s not clear whether vaccinated people may still spread the virus, but the answer to that question is coming soon. Until then, scientists urge caution.A health care worker prepared a dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine at a vaccination site in San Francisco on Monday.Credit…Mike Kai Chen for The New York TimesMarch 3, 2021, 3:23 p.m. ETWith 50 million Americans immunized against the coronavirus, and millions more joining the ranks every day, the urgent question on many minds is: When can I throw away my mask?It’s a deeper question than it seems — about a return to normalcy, about how soon vaccinated Americans can hug loved ones, get together with friends, and go to concerts, shopping malls and restaurants without feeling threatened by the coronavirus.Certainly many state officials are ready. On Tuesday, Texas lifted its mask mandate, along with all restrictions on businesses, and Mississippi quickly followed suit. Governors in both states cited declining infection rates and rising numbers of citizens getting vaccinated.But the pandemic is not yet over, and scientists are counseling patience.It seems clear that small groups of vaccinated people can get together without much worry about infecting one another. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is expected shortly to issue new guidelines that will touch on small gatherings of vaccinated Americans.But when vaccinated people can ditch the masks in public spaces will depend on how quickly the rates of disease drop and what percentage of people remain unvaccinated in the surrounding community.Why? Scientists do not know whether vaccinated people spread the virus to those who are unvaccinated. While all of the Covid-19 vaccines are spectacularly good at shielding people from severe illness and death, the research is unclear on exactly how well they stop the virus from taking root in an immunized person’s nose and then spreading to others.It’s not uncommon for a vaccine to forestall severe disease but not infection. Inoculations against the flu, rotavirus, polio and pertussis are all imperfect in this way.The coronavirus vaccines “are under a lot more scrutiny than any of the previous vaccines ever have been,” said Neeltje van Doremalen, an expert in preclinical vaccine development at the National Institutes of Health’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Montana.And now coronavirus variants that dodge the immune system are changing the calculus. Some vaccines are less effective at preventing infections with certain variants, and in theory could allow more virus to spread.The research available so far on how well the vaccines prevent transmission is preliminary but promising. “We feel confident that there’s a reduction,” said Natalie Dean, a biostatistician at the University of Florida. “We don’t know the exact magnitude, but it’s not 100 percent.”Still, even an 80 percent drop in transmissibility might be enough for immunized people to toss their masks, experts said — especially once a majority of the population is inoculated, and as rates of cases, hospitalizations and deaths plummet.A line to register for a vaccination appointment in San Francisco. Experts say that people who have been inoculated should continue to wear masks to protect others.Credit…Mike Kai Chen for The New York TimesBut most Americans are still unvaccinated, and more than 1,500 people are dying every day. So given the uncertainty around transmission, even people who are immunized must continue to protect others by wearing masks, experts said.“They should wear masks until we actually prove that vaccines prevent transmission,” said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases.The Coronavirus Outbreak

Read more →