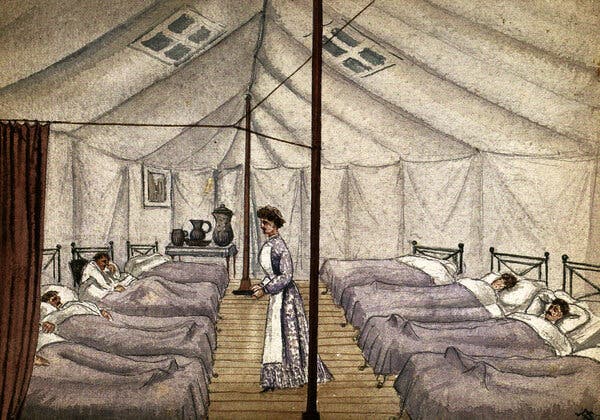

Los brotes generalizados de enfermedades tienen el potencial de sacudir a las sociedades para que adopten nuevas formas de vida.Hace cinco años, decidí escribir una novela ambientada en las secuelas de una terrible pandemia.La novela era una historia alternativa, un western revisionista ambientado en el siglo XIX, y acabé investigando en abundancia sobre todo tipo de temas, desde las marcas de ganado hasta la obstetricia. Pero me avergüenza admitir que mi investigación sobre las catástrofes sanitarias fue un tanto escasa. Básicamente, analicé una lista de brotes de gripe, elegí el que se adaptaba mejor a mi argumento (una pandemia de 1830 que podría haber empezado en China) y empecé a escribir.Pero cuando terminé el libro, sus acontecimientos chocaron con el presente. En marzo de 2020 estaba trabajando en las correcciones cuando la ciudad de Nueva York, donde vivo, empezó a cerrar. De repente, tuve mucho tiempo, y mucha motivación, para considerar lo que había acertado y lo que no sobre la devastación que la enfermedad genera en una sociedad.En muchos aspectos, mi imaginación se había alejado de la realidad. Por un lado, ninguna pandemia conocida ha sido tan mortal como la que escribí, que mata al 90 por ciento de la población estadounidense. Sin embargo, tuve un instinto que resultó ser correcto: las pandemias tienen el potencial de conmocionar a las sociedades para que adopten nuevos estilos de vida. La peste negra, por ejemplo, provocó el fin de la servidumbre feudal y el ascenso de la clase media en Inglaterra.No obstante, un brote de enfermedad también puede hacer que los gobiernos redoblen la represión y el fanatismo, como cuando Estados Unidos utilizó como chivo expiatorio a los estadounidenses de origen asiático durante las epidemias de peste del siglo XIX.Una pintura del Hospital de Viruela de San Pancracio, alrededor de la década de 1880, en un campamento provisional en Londres.Frank Collins/Buyenlarge, vía Getty ImagesLa historia no puede decirles a los políticos y activistas estadounidenses con exactitud cómo responder a la COVID-19; más bien ofrece ejemplos de lo que no se debe hacer. Sin embargo, los brotes en la Sudáfrica del siglo XX, la Inglaterra medieval, la antigua Roma y otros lugares pueden ofrecer algunas lecciones para quienes trabajan con el fin de curar los daños de la COVID y forjar una sociedad más justa tras su paso.Hace cinco años, la historia de las pandemias fue un punto de partida para mí, una inspiración, y poco más. Ahora es algo más urgente: representa lo que podemos esperar en estos tiempos oscuros, así como lo que nos espera si no actuamos. A continuación enumero algunas lecciones aprendidas.AdaptarseLa peste negra, una pandemia causada por la bacteria Yersinia pestis que se extendió por Asia, África y Europa a partir de 1346, fue “sin duda la crisis sanitaria más catastrófica de la historia”, dijo en una entrevista Mark Bailey, historiador y autor de After the Black Death: Economy, Society, and the Law in Fourteenth-Century England. En Inglaterra, la peste mató a cerca del 50 por ciento de la población en 1348 y 1349; en el conjunto de Europa, las estimaciones oscilan entre el 30 y el 60 por ciento. La magnitud de la mortandad fue un impacto enorme, aunque sus efectos fueron mucho más allá. Como dijo Monica Green, historiadora de la medicina que se ha especializado en la Europa medieval: “¿Quién va a recoger la cosecha si la mitad de la gente desapareció?”.Diversas sociedades han respondido de manera diferente. En muchas partes del noroeste de Europa, como Gran Bretaña y lo que hoy son los Países Bajos, la muerte repentina de una gran parte de los trabajadores significaba que era más fácil para los sobrevivientes conseguir trabajo y adquirir tierras. “Se produce un aumento de la riqueza per cápita y una reducción de la desigualdad de la riqueza”, explicó Bailey. Desde un punto de vista económico, al menos, “la gente corriente está mejor”. “Huida de los habitantes del pueblo al campo para escapar de la plaga”, de 1630. La plaga se representa en el extremo derecho como un esqueleto que sostiene una daga y un reloj de arena./Universal Images Group, vía Getty ImagesLo contrario ocurrió en gran parte de Europa del Este, donde los terratenientes consolidaron su poder sobre el campesinado, ahora escaso, para volver a imponer la servidumbre y obligarlos a trabajar la tierra en condiciones favorables para los poderosos. Allí, la desigualdad se estabilizó o incluso aumentó a raíz de la peste.Hay muchas explicaciones distintas pero una posibilidad es que “la peste negra tiende a acelerar las tendencias existentes”, por ejemplo, el movimiento hacia una economía menos feudal y más basada en el consumo en el norte de Europa, explicó Bailey. Pero esa región no se convirtió por arte de magia en un bastión de la igualdad después de la peste: el gobierno inglés impuso topes salariales a mediados del siglo XIV para evitar que los sueldos subieran demasiado. El resultado fue un malestar generalizado, que culminó en la Revuelta de los Campesinos de 1381, que reunió a personas de muy diversos orígenes sociales en una expresión de “frustración contenida” por la mala gestión de la economía por parte del gobierno, dijo Bailey.En general, si “la resiliencia en una pandemia es hacer frente”, continuó, “posteriormente, la resiliencia económica y social consiste en adaptarse”. La lección moderna sería: “Adaptarse a la nueva realidad, al nuevo paradigma, a las nuevas oportunidades, es la clave”.Combatir la desigualdadEl avance hacia una mayor igualdad económica en Inglaterra tras la peste puede haber sido un poco atípico: a lo largo de la historia, las epidemias tienden a intensificar las desigualdades sociales existentes.En 1901, por ejemplo, cuando una epidemia de peste azotó Sudáfrica, “miles de sudafricanos negros fueron expulsados a la fuerza de Ciudad del Cabo bajo la suposición de que su libre circulación estaba influyendo en la propagación de la peste dentro de la ciudad”, dijo Alexandre White, profesor de sociología e historia de la medicina cuyo trabajo se enfoca en la respuesta a las pandemias. Esa expulsión sentó las bases de la segregación racial de la época del apartheid.Estados Unidos también tiene un historial de políticas discriminatorias durante las epidemias, como la focalización en las comunidades asiático-estadounidenses durante los brotes de peste de principios del siglo XIX y principios del XX en Hawái y San Francisco, y la lenta respuesta federal a la epidemia de VIH cuando parecía afectar sobre todo a los estadounidenses de la comunidad LGBTQ, dijo White. Ese tipo de decisiones han ampliado no solo la desigualdad, sino que también han obstaculizado los esfuerzos para combatir la enfermedad: ignorar el VIH, por ejemplo, permitió que se extendiera por toda la población. Un científico que estudiaba la plaga en un laboratorio de San Francisco en 1961.Smith Collection/Gado/Getty ImagesY ahora, Estados Unidos se enfrenta a una pandemia que ha enfermado y matado de manera desproporcionada a los estadounidenses de color, quienes conforman buena parte de la mano de obra esencial pero tienen menos probabilidades de acceder a la atención médica. Mientras los gobiernos federales y estatales gestionan el despliegue de las vacunas, el acceso a las pruebas y al tratamiento, y los paquetes de ayuda económica, es crucial aprender del pasado y dirigir las políticas que reduzcan las desigualdades raciales y económicas que hicieron que la pandemia fuera tan devastadora.“Si los efectos del racismo y la xenofobia fueran menos sistémicos en nuestra sociedad, probablemente veríamos menos muertes como resultado de la COVID-19”, comentó White. “La intolerancia es, de manera sustancial, mala para la salud pública”.Adoptar la innovación inesperadaAunque las pandemias han reafirmado viejos prejuicios y modos de marginación, también han generado cosas nuevas, especialmente en cuanto al arte, la cultura y el entretenimiento.La antigua Roma, por ejemplo, estaba atormentada por las epidemias, que se producían cada quince o veinte años durante los siglos IV, III y II a. C., explica Caroline Wazer, escritora y editora que realizó una tesis sobre la salud pública romana. En aquella época, la principal respuesta en materia de salud pública era la religiosa, y los romanos experimentaban con nuevos ritos e incluso con nuevos dioses en un intento por detener la propagación de la enfermedad. En un caso, según Wazer, puesto que una epidemia que se prolongaba durante tres años y el público estaba cada vez más agitado, el Senado adoptó un extraño y nuevo ritual del norte de Italia que consistía en traer “actores para que se presentaran en el escenario”. Según el historiador romano Livio, “así es como los romanos tuvieron su teatro”, dijo Wazer, aunque esa idea ha sido debatida.Una respuesta espiritual a la enfermedad también provocó un cambio cultural en la Inglaterra del siglo XIV. Recordando las fosas comunes de la peste negra, los británicos temían morir sin un entierro cristiano y pasar la eternidad en el purgatorio, dijo Bailey. Así que empezaron a formar gremios, pequeños grupos religiosos que funcionaban básicamente como “clubes de seguros de entierro”, en los que recaudaban dinero para dar a sus miembros el tratamiento adecuado tras la muerte.Esas cofradías organizaban fiestas y otros eventos, y con el tiempo surgió la preocupación “por el consumo de cerveza en la iglesia y sus alrededores”, dijo Bailey. Así que los gremios comenzaron a construir sus propios salones para socializar. Luego, durante la Reforma en el siglo XVI, los gremios se disolvieron y los salones se convirtieron en algo nuevo: los pubs.De hecho, los historiadores han argumentado que el aumento del consumismo y la riqueza de la gente común después de la peste negra allanó el camino para la cultura de los pubs por la que Inglaterra sigue siendo conocida hoy en día.Sería frívolo calificar a esas innovaciones culturales como un “rayo de luz” originado por las pandemias; después de todo, han surgido muchas formas de arte y nuevos lugares sociales sin el catalizador de las muertes masivas. Sin embargo, vale la pena recordar que, incluso a raíz de los desastres de salud pública más devastadores, la vida social y la creatividad humana han resurgido de formas nuevas e inesperadas.“Las pandemias son tanto catástrofes como oportunidades”, me dijo Bailey. En los próximos años, el mundo se enfrentará a la trágica oportunidad de reconstruirse tras la COVID-19. Si aprendemos las lecciones de la historia, quizá podamos hacerlo de una manera más justa, más inclusiva e incluso más alegre que el pasado que nos hemos visto obligados a superar.Anna North es reportera sénior en Vox y autora de tres novelas, entre ellas Outlawed, la más reciente.

Read more →