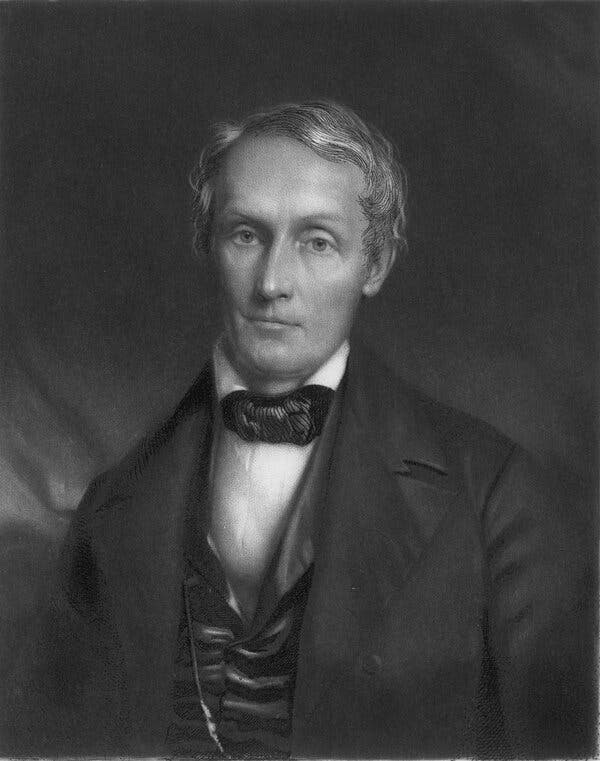

As one museum has pledged to return skulls held in an infamous collection, others, including the Smithsonian, are reckoning with their own holdings of African-American remains.The Morton Cranial Collection, assembled by the 19th-century physician and anatomist Samuel George Morton, is one of the more complicated holdings of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.Consisting of some 1,300 skulls gathered around the world, it provided the foundation for Morton’s influential racist theories of differences in intelligence among races, which helped establish the now-discredited “race science” that contributed to 20th century eugenics. In recent years, part of the collection was prominently displayed in a museum classroom, a ghoulish object lesson in an infamous chapter of scientific history.Last summer, after student activists highlighted the fact that some 50 skulls had come from enslaved Africans in Cuba, the museum moved the displayed skulls into storage with the rest of the collection. And last week, shortly after the release of outside research indicating roughly 14 other skulls had come from Black Philadelphians taken from pauper’s graves, the museum announced that the entire collection would be opened up for potential “repatriation or reburial of ancestors,” as a step toward “atonement and repair” for past racist and colonialist practices.The announcement was the latest development in a highly charged conversation about African-American remains in museum collections, especially those of the enslaved. In January, the president of Harvard University issued a letter to alumni and affiliates acknowledging that the 22,000 human remains in its collections included 15 from people of African descent who may have been enslaved in the United States, and pledging to review its policies of “ethical stewardship.”And now, that conversation may be set to explode. In recent weeks, the Smithsonian Institution, whose National Museum of Natural History houses the nation’s largest collection of human remains, has been debating a proposed statement on its own African-American remains.Those discussions, according to portions of an internal summary obtained by The New York Times, have involved people who have long prioritized repatriation efforts as well as those who take a more traditional view of the museum’s mission to collect, preserve and study artifacts, and who view repatriations as potential losses to science.In an interview last week, Lonnie G. Bunch III, the secretary of the Smithsonian, declined to characterize the deliberations but confirmed the museum was developing new guidance, which he said would be undergirded by a clear imperative: “to honor and remember.”“Slavery is in many ways the last great unmentionable in American discourse,” he said. “Anything we can do to both help the public understand the impact of slavery, and find ways to honor the enslaved, is at the top of my list.”The anthropologist Samuel George Morton began collecting the skulls in the 1830s, as part of an effort to prove differences in intelligence across races.Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAny new policy, Dr. Bunch said, would build on existing programs for Native American remains. It could involve not just the return of remains to direct descendants, but possibly to communities, or even reburial in a national African-American burial ground. And the museum, he said, would also strive to tell fuller stories of individuals whose remains stay in the collection.“It used to be that scholarship trumped community,” he said. “Now, it’s about finding the right tension between community and scholarship.”The quantity of enslaved and other African-American remains in museums may be modest compared with the estimated 500,000 Native American remains in U.S. collections, which were scooped up from burial grounds and 19th-century battlefields on what Samuel J. Redman, an associate professor of history at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, termed “an industrial scale.”But Dr. Redman, the author of “Bone Rooms,” a history of remains collecting by museums, said the moves by Harvard, Penn and especially the Smithsonian could represent a “historical tipping point.”“It puts into shocking relief our need to address the problem of the historical exploitation of people of color in the collecting of their objects, their stories and their bodies,” he said.The complexities around African-American remains — who might claim them? how do you determine enslaved status? — are enormous. Even just counting them is a challenge. According to an internal Smithsonian survey that has not previously been made public, the 33,000 remains in its storerooms include those from roughly 1,700 African-Americans, including an estimated several hundred who were born before 1865, and so may have been enslaved.A page from from Morton’s “Crania Americana,” one of a series of works outlining a supposed hierarchy of intelligence based on skull size, with Europeans on top.via National Library of MedicineMorton’s work helped establish the dubious “race science” that flourished in the 19th century and went on to contribute to 20th century eugenics.via National Library of MedicineSome remains come from archaeological excavations. But the majority are from individuals who died in state-funded institutions for the poor, whose unclaimed bodies ended up in anatomical collections that were later acquired by the Smithsonian.In addition to the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which requires museums to return remains to tribes or lineal descendants that request them, the Smithsonian allows remains from named individuals of any race to be claimed by descendants. While many African-American individuals in the anatomical collections are named, none have ever been reclaimed, according to the natural history museum.Kirk Johnson, the museum’s director, said that the anatomical collections, while disproportionately gathered from the poor and marginalized, included a cross-section of society in terms of age, sex, race, ethnicity and cause of death, which had made them extremely useful for forensic anthropologists and other researchers.But when it comes to African-American remains, a broader approach to repatriation — including a more expansive notion of “ancestor” and “descendant” — may be justified.“We’ve all had a season of becoming more enlightened about structural racism and anti-Black racism,” he said. “At the end of the day,” he added, “it’s a matter of respect.”Dr. Bunch, the Smithsonian’s first Black secretary, said he hoped its actions would provide a model for institutions across the country. Some who have studied the history of the trade in Black bodies say such guidance is sorely needed.In early April, new research claiming that the collection included roughly 14 skulls of Black Philadelphians taken from pauper’s graves in the 1830s and 1840s prompted renewed protests.Sukhmani Kaur“It would be wonderful to have an African-American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act,” said Daina Ramey Berry, a professor of history at the University of Texas and author of “The Price for Their Pound of Flesh,” a study of the commodification of enslaved bodies from birth to death.“We’re finding evidence of enslaved bodies used at medical schools throughout the nation,” she said. “Some are still on display at universities. They need to be returned.”Penn’s Morton collection vividly embodies both the sordid side of the enterprise, and the way the meanings of collections change.Morton, a successful doctor who was an active member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, has sometimes been called the founder of American physical anthropology. He was a proponent of the theory of polygenesis, which held that some races were separate species, with separate origins. In books like the lavishly illustrated “Crania Americana,” from 1839, he drew on skull measurements to outline a proposed hierarchy of human intelligence, with Europeans on top and Africans in the United States at the bottom.Morton’s skull collection was said to be the first scholarly anatomical collection in the United States and, at the time, the largest. But after his death in 1851, it fell into obscurity, even as his racist ideas about differences in intelligence remained influential.In 1966, the collection was relocated to the Penn Museum, from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. And it quickly became a useful tool for all sorts of scientific research — including studies aimed at debunking the racist ideas it had helped create.In a famous 1978 paper (later adapted for his book “The Mismeasure of Man”), the paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould argued that Morton’s racist assumptions had led him to make incorrect measurements — thus turning Morton into a symbol not just of racist ideas, but of how bias can affect the seemingly objective procedures of science.The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, which has the country’s largest collection of human remains, is debating a statement on potential repatriation of African-American remains.Robert Alexander/Getty ImagesGould’s analysis of Morton’s measurements has itself been hotly disputed. But in recent years, the appropriateness of possessing the skulls at all has been sharply questioned by campus and local activists, particularly after student researchers connected with the Penn & Slavery Project drew attention to the remains of the enslaved Cubans.Christopher Woods, who became the museum’s director earlier this month, said the new repatriation policy (which was recommended by a committee) would not change the collection’s status as an active research source.Although there has been no access to the actual skulls since last summer, legitimate researchers can examine 3-D scans of the entire collection, including those of 126 Native Americans that have already been repatriated.“The collection was put together for nefarious purpose in the 19th century, to reinforce white supremacist racial views, but there’s still been good research done on that collection,” Dr. Woods said.When it comes to repatriation, he said, the moral imperative is clear, even if the specific course of action may not be. For the skulls of Black Philadelphians taken from pauper’s graves (a major source for cadavers of all races at the time), he said the hope is they can be reburied in a local African-American cemetery.The enslaved remains from Cuba, however, would require future research and possibly testing, as well as a search for an appropriate repatriation site, possibly in Cuba or West Africa, where most of the individuals were likely born.The Black remains may have become a particularly urgent issue, he said. But repatriation requests for any skulls would be considered.“This is an ethical question,” he said. “We need to consider the wishes of the communities from whence these people came.”

Read more →