On a wrinkled sheet of lined paper tucked in my mom’s purse was a list of places we had jotted down, memories to visit. It was January 2020, and my mother and I were on a trip to Chicago, to see the places from her past and my early childhood in and around the Englewood section of the city, where she was born and raised, and where I was, too, before we moved to Denver in 1969. As we drove south in our rental car, from Roosevelt University on South Michigan Avenue, where Mom attended college in the 1950s, toward what was called the Black Belt, I imagined myself as a 7-year-old sitting on the second-floor balcony of my great-aunt’s brick building on South Vernon Avenue, watching people bustle below. I would strain to hear my mother soaking in news and gossip from her aunties, their voices soft and Southern, before I was shooed away, warned to stay out of grown folks’ business.I was most excited to revisit Brice’s, the liquor shop on South Vernon Avenue owned by my dad’s close friend. Most Saturdays, while my mother visited her family a few blocks away, my father would stop in to hang out and talk about fishing with Mr. Brice, whom I remember giving my sister and me free candy and ice cream sandwiches. His store served as a welcoming kind of community center for the neighborhood, and the oaky smell of any liquor shop still brings back that memory. Thinking of the sheltering arms and safe embrace of family and neighbors in that community, a line from the Chicago poet Gwendolyn Brooks came to mind: “that we are each other’s harvest:/we are each other’s business:/we are each other’s magnitude and bond.”But the mixed-income, largely working-class Black neighborhood we remembered was mostly gone. My mother’s childhood apartment had been razed, reduced to a garbage-strewn vacant lot. The home she and my father lived in after they married was boarded up, as was her elementary school, Betsy Ross. Harvard Elementary, where I went, was still there, now known as the John Harvard Elementary School of Excellence, but many of the houses across the street were abandoned, as were several nearby storefronts. Englewood High School was closed in 2008 because of poor performance. Mr. Brice’s was long gone, and the corner looked seedy enough that I refused to let my fearless 89-year-old mother get out of the car.Englewood — near the middle of the country’s third-largest city — reminded me of the rural Mississippi my grandmother and her siblings left behind for safety and greater opportunities nearly a hundred years ago during the Great Migration. But it is Chicago, not the rural South, that has the country’s widest racial gap in life expectancy: In the Streeterville neighborhood, nine miles north, which is 73 percent white, residents live, on average, to 90 years old; in Englewood, where nearly 95 percent of residents are Black, people live to an average of only 60.Over this past year, Black lives have been cut even shorter by Covid-19, which strikes marginalized communities disproportionately, creeping into the fault lines of our society. Black Americans have been hospitalized with Covid-19 at nearly three times the rate of white Americans, and the death rate is twice as high. The deaths have taken a toll: In the first six months of the pandemic, the average life span of an American declined by a full year: from 78.8 years in 2019 to 77.8 years in the first half of 2020. But Black life expectancy plummeted more, declining by nearly three years in the same time frame.One in 379 Black Chicagoans have died due to Covid-19. In Englewood’s 60621 ZIP code, 1 in 363 people have died due to Covid, compared with 1 in 2,162 people in Streeterville’s 60611 ZIP code. That same Streeterville ZIP code had one of the highest Covid vaccination rates in the city, with 42.6 percent of residents having received a full series and 60.7 percent one dose by late April. Englewood’s 60621 ZIP code had one of the lowest vaccination rates in the city, with 14.2 percent having received a full series and only 22.1 percent at least one dose.But long before the pandemic, the story of Chicago’s yawning disparity between Black and white life spans was written through my own family history. How did a Promised Land to generations of Black families become a community of lost lives?The author’s family in Chicago in 1962; the author at her family’s home on South Wentworth; her great-aunt and -uncle’s former home on 62nd and South Vernon in January 2020.Photo illustration by Mark HarrisMy seven great-aunts and -uncles, the Clement family, left Mississippi in the mid-1920s. Like so many African-Americans, they fled the South to escape the indignities and menace of Jim Crow laws and the epidemic of lynchings and other forms of racial terrorism, and to pursue the chance to work in a thriving economy fueled by rapidly growing factories, mills and packinghouses. One sister went to New York City, one to Cleveland and another to Detroit. The other four siblings chose Chicago. They had read articles about the city in The Chicago Defender, the Black newspaper that was circulated widely throughout the South, and boarded the Illinois Central together. My grandmother Mollie Dee, still a teenager, stayed behind on the farm that their parents, Charles and Mahalia, owned in Iuka, a city in the northeastern part of Mississippi.My great-aunts and -uncles settled on the South Side in the area where most of the Black population resided, which stretched from 22nd Street to 31st Street along State Street and later expanded south. Beginning in 1916, as Black Southerners poured into the city, the Chicago Real Estate Board promoted a set of racially restrictive covenants that allowed property owners to keep certain communities white by preventing Black people from occupying, renting or buying housing. Increasing numbers of newly arrived Black residents were hemmed into specific neighborhoods, including the area where my family put down roots.My mother’s classmate Lorraine Hansberry used what happened to her family as inspiration for her 1959 play, “A Raisin in the Sun.” The Hansberrys bought their home in 1937, in an area whiter than where our family lived, just south of the University of Chicago. Mobs confronted the family, and a white neighbor sued the Hansberrys, contending that a restrictive agreement prevented Black people from buying homes in the neighborhood. Carl Hansberry, Lorraine’s father, challenged the case, and in 1940 Hansberry v. Lee reached the U.S. Supreme Court. He won, and that suit laid the groundwork for a later case that struck down the racist covenants in 1948.‘Now you drive through communities like Englewood and see empty lot after empty lot after empty lot.’My Aunt Sweetie, who could barely read or write, managed to scrimp and save the money she earned as a maid and bought a two-story brick home on 62nd and South Vernon Avenue, big enough to house several family members. My Aunt Lottie and her husband, Brother Harry, opened a grocery store nearby on South Parkway. My grandmother, the youngest of the Clement children, made her way to Chicago several years after her older siblings, in 1928. She moved into the home on South Vernon and also worked as a maid. Shortly after she arrived, she met my grandfather, Homer Alexander, at a dance. He was also from Mississippi and was captivated by her free spirit and flouncy flapper dress. They married in 1929.By then, the Black population of Chicago had ballooned to about 7 percent from 2 percent in 1910. White residents had fled from the area known as Bronzeville on the South Side, which had become home to a vast majority of African-American Chicagoans — about a quarter million by 1930. The stark segregation would be reflected in dramatically different statistics for disease and death.While race affects health outcomes regardless of income and education, and longstanding discrimination in the institutions and structures of American society erodes the health and well-being of all Black Americans, health most directly correlates with the resources a community has to offer. From the beginning of life to the end, the environment where people make their homes, work, attend school, play and worship has a profound influence on health outcomes. Wealthy communities tend to be safer and have adequate health care services, outdoor space, clean air and water, public transportation and affordable healthful food, as well as opportunities for education, employment and social support that all contribute to longer, healthier lives. Poorer communities generally lack a healthful environment and basic services and support, which makes the lives of residents more difficult and ultimately shorter. Violence, too, is harder to keep at bay in neighborhoods that lack options, services and hope.In Englewood, about 60 percent of the residents have a high school diploma or equivalency or less, and 57 percent of households earn less than $25,000 a year. Streeterville, on the other side of Chicago’s chasm, has a median income of $125,000. The vast majority of residents there have at least a college degree; 44 percent have a master’s degree or higher. And, predictably, Englewood has long shouldered an unequal burden of disease. It has among the city’s highest rates of deaths from heart disease and diabetes, as well as rates of infant mortality and children living with elevated blood-lead levels, according to the Chicago Department of Public Health. These differences all lead up to that irrefutable racial gap in life spans.“It is very clear that life expectancy is most influenced by geography,” said Dr. Judith L. Singleton, a medical and cultural anthropologist who is conducting an ongoing study at Northwestern University about life expectancy inequality across Chicago neighborhoods. Her father came to Chicago from New Orleans in the 1930s and settled in Bronzeville. In 1960, her parents bought a home on the far South Side. After her mother died, she finally moved her dad out of his home after 40 years because of a lack of services, including nearby grocery stores, and fear for his safety. “If you live in a neighborhood with lots of resources and higher incomes, your chances of a longer life are better — and the opposite is true if your community has few resources,” she said. “There’s something really wrong with that.”Historically, there has been a damning explanation of why poor communities have crumbling conditions and a dearth of services: not that something is wrong that needs to be fixed, but that something is wrong with the people and the community themselves. It’s their fault; they did this to themselves by not eating right, by avoiding medical care, by being uneducated. Nearly every time former President Donald Trump opened his mouth to speak about Black communities in Detroit, Baltimore, Atlanta and, yes, Chicago, he parroted the underlying assumption that Black communities in America are solely to blame for their own problems. In 2019, during sworn testimony before Congress, Trump’s former lawyer Michael Cohen claimed that his boss had characterized Black Chicago with disdain and blame: “While we were once driving through a struggling neighborhood in Chicago,” Trump “commented that only Black people could live that way.” In 2018, the American Values Survey found that 45 percent of white Americans believed that socioeconomic disparities are really a matter of not trying hard enough — and that if Black people put in more effort, they could be just as well off as white people.What really happened was more sinister. On the South Side of Chicago, a pattern of intentional, government-sanctioned policies systematically extracted the wealth from Black neighborhoods, bringing an erosion of health for generations of people, leaving them to live sick and die young.Like mine, Dr. Eric E. Whitaker’s family traveled a path up North from Mississippi to the South Side of Chicago. I met Whitaker, a physician and former director of the Illinois Department of Public Health, in 1991, when I was a health-communications fellow at what is now known as the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He was in medical school at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, taking a year off to earn his master’s in public health. After we became friends, we discovered that his maternal grandparents had owned a three-flat building around the corner from our family home on South Vernon Avenue.He recalls the area as a thriving mixed-income neighborhood, a place of comfort, full of life and energy, though all that remains of his grandparents’ building is a memory and a pile of rubble. “What I remember of my grandparents’ home was the vitality,” said Whitaker, who would meet his close friend Barack Obama during the year he spent at Harvard, when Obama was at Harvard Law School. “There would be people on porches, kids playing in the streets. It was aspirational. Now you drive through communities like Englewood and see empty lot after empty lot after empty lot. Every once in a while I take my kids to see where Dad came from. When I show them the vacant lot where Grandma’s house used to be, they think, Wow, this is sad.”But what Whitaker and I remember with a warm glow wasn’t the whole story. Even as our relatives were starting their hopeful new lives in the 1930s, the government-sanctioned practice of redlining arose in response, enforcing segregation, lowering land and property values and seeding disinvestment and decay for more than 30 years.When my grandmother became pregnant with my mom in 1929, my grandparents rented a house on the same block as Brother Harry’s grocery store. My mom was born at home in 1930, my Uncle Homer the following year. My grandfather worked as a bellhop at a downtown hotel on Michigan Avenue, while my grandmother, who had gone to beauty school, was doing hair out of a salon not far from the house on South Vernon. During the Depression, my grandfather left Chicago to find work. My grandmother couldn’t hold onto their rental apartment and moved with her children to 59th and South Prairie, next to the L tracks. My mother remembers sitting in front of the window in the room she shared with her brother, watching the trains rumble by full of white people on the way to and from work and hoping her father would return home soon. When we visited last year, my mother pointed to a desolate patch of land. “It used to be right there,” she said.‘Our own federal policies actually created a lot of the conditions that people now are faced with.’A few years later, after my grandfather returned, he was hired as a Pullman porter, one of the best jobs available to Black men at the time. Though hauling suitcases and serving white folks traveling on trains in sleeping cars was backbreaking, sometimes demeaning work, it provided a firm financial footing for my grandparents and a toehold into middle class that allowed them to put money aside. In the early 1940s, they bought a solid two-flat building on East 64th Place. They lived on the first floor and rented the second floor and the basement. I asked my mother how Grandfather could afford the down payment, and she told me he didn’t have a mortgage; he bought the house on some kind of contract.Beginning in the 1940s, speculators created home-sale contracts to trap African-American families who were eager to purchase homes but whose housing choices were restricted by racial segregation and redlining. These contracts offered Black buyers the false impression of a mortgage but without the protections. Instead, buyers made monthly installments at high interest rates toward bloated purchase prices, but never gained ownership until the contract was paid in full and all conditions met. That meant that contract sellers held the deed of the home and were able to evict the buyers for any missed payments. Black contract buyers accumulated no equity in their homes. Though activists fought this housing injustice, in the 1950s and 1960s more than 75 percent of Black home buyers in Chicago bought on contract, like my grandparents did.According to the 2019 report “The Plunder of Black Wealth in Chicago,” released by the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University, this practice extracted between $3.2 billion and $4 billion from Chicago’s Black community. “The curse of contract sales still reverberates through Chicago’s Black neighborhoods (and their urban counterparts nationwide),” the report’s authors wrote, “and helps explain the vast wealth divide between Blacks and whites.” My mother recalls that her father was always terrified about missing a payment because he knew he could lose his building — and their home — at any time.In 1953, my mother was attending the graduate school of social work at Loyola University, and doing her fieldwork in the psychiatric unit at Edward Hines Jr. V.A. Hospital. My dad, Andres Villarosa, was working as a bacteriologist at the same hospital and gave my mother a ride to work one day. They were married in 1954 and moved into a two-bedroom apartment on 64th and South Vernon, in a building owned by a friend of my grandmother’s not far from where my mother’s aunts and uncles lived. She couldn’t find the house when we visited. I pointed to a building with boarded-up windows, peeling paint on the trim and splintered steps leading to the doorway. “Mom, is that it?” She nodded.My grandparents managed to hold onto their building, and in 1958 my grandmother persuaded my grandfather to buy another one; but this time they were able to get a real mortgage. In the early 1960s, after my sister and I were born, our family moved into the building on 75th and South Wentworth with our grandparents.But by the time I was in third grade at Harvard Elementary School, the toxic combination of housing covenants, redlining and contract buying had sapped the life out of many of the neighborhoods on the South Side. The city’s deliberate placement of high-rise public-housing projects in Black communities effectively concentrated poverty and limited economic opportunity for public-housing residents. The unemployment rate for Black Chicagoans was 12.8 percent, compared with 6.7 percent for their white counterparts. By that year, the city’s homicide rate had more than doubled from a decade before, and nearly one-third of all Black residents lived below the poverty level.“The neighborhoods that we’re talking about are the way they are largely because of social and public policies that really so destroyed many cities, and particularly Black and brown neighborhoods,” said Dr. Helene Gayle, a physician who spent 20 years at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is now the president and C.E.O. of the Chicago Community Trust, a philanthropic community organization focused on addressing the racial and ethnic wealth gap. “These are not about choices,” Gayle continued. “These are about the reality of options that people have in their lives or don’t have in their lives and how our own federal policies actually created a lot of the conditions that people now are faced with.”I remember my parents’ complaints about Chicago and whisper-hiss conversations about how they needed to get out of the city. They looked in a mostly white suburb near my father’s job at Hines Hospital. While house hunting, my mother asked a police officer if the area would be safe for a Black family, and he told her, “I can’t guarantee that we could protect you and your family.” My mom later told me, “That was all I needed to know; we couldn’t move there. If someone hurt my baby girls, your father would kill them, he would go to jail and I’d be a single mother.”Mollie Dee Alexander, the author’s grandmother; the author’s parents in the 1970s; the author’s mother at Betsy Ross Elementary School, January 2020.Photo illustration by Mark HarrisIn 1969, my father applied for a transfer to Denver, and my parents packed up our Rambler station wagon and moved the family to the suburb of Lakewood, Colo. We were part of a larger trend of Black suburbanization: In the 1970s, the overall Black population in American suburbs increased by 70 percent as families like mine left the city, taking advantage of a world newly expanded by civil rights legislation that finally dismantled some of the institutional discrimination in housing and education.Leaving Chicago, the only city she had ever known, and moving far away from her parents and extended family was especially wrenching for my mother. But my parents wanted to get out of a rapidly decomposing Black Chicago and give my sister and me a better childhood than the one they had. To them it meant we would grow up in a house with a backyard, not an apartment near the Dan Ryan Expressway; go to a school with a cafeteria, not run to the church across the street at noon to eat a free lunch served by volunteers in the basement. We would learn alongside the white children, play outside with them in the safe streets of our suburban community and get all the privileges reserved for them that weren’t available in the resource-starved Black neighborhoods of Chicago.Around the time we left, many other Black working- and middle-class families left Chicago, too. Englewood hemorrhaged Black people: According to data gathered by the Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois, Chicago, between 1970 and 2019, almost 65,000 Black residents relocated, a decrease of 75 percent, even though the neighborhood remains almost all Black. Between 1980 and 2019, the overall Black population of Chicago fell by more than 33 percent, a loss of some 400,000 residents.As middle-class families departed and wealth shrank, so did services and support. For the first half of the 20th century, Englewood was home to the city’s largest shopping district outside of the Loop. But as the neighborhood declined, several large department stores and many small businesses left or closed shop. A 2013 investigation by the WBEZ radio station found that since 2002, about 200 Chicago public schools had either shut down or been radically shaken up, with 50 schools closing in 2013 alone; of the more than 70,000 students who experienced a school closure or complete restaffing, 88 percent were Black. Between 1970 and 1991, 36 percent of Chicago’s hospitals closed, many of them serving communities of color. Michael Reese, the hospital on South Ellis Avenue where Eric Whitaker’s mother worked as a nurse for more than 30 years, and where Whitaker and his two brothers were born, closed in 2008; demolition began the next year. As these trends drained the lifeblood from communities, a 2010 analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health found that virtually no progress was made in the previous 15 years to close the city’s racial health gap. “You can take a map of poverty,” Whitaker said, “overlay with every class of disease and it’d be the same place.”In 1997, Whitaker helped found Project Brotherhood, a weekly clinic for Black men, in the Woodlawn neighborhood. Though a full-service clinic supported by the Cook County health system was already in place, Whitaker and his colleagues noticed that Black men rarely used it. “We ended up going to do focus groups with men from the community to ask them the question: ‘You have a resource here, why don’t you use it?’” he said. “And the answer was that men felt disrespected by the health care system. Others said they didn’t want people to see them going to the center or they just didn’t find it a place of comfort. That meant they were delaying care they absolutely needed to get.”But according to a 2016 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, access to medical care accounts for only 20 percent of the contributors to healthy outcomes; socioeconomic and environmental factors of the community, at 50 percent, are far more important. “My ideas over time have evolved as I’ve gotten more exposed to the explicit tie between health and wealth,” said Whitaker, who now runs Zing Health, which offers Medicare Advantage health plans for underserved seniors. “I feel you can make more of an impact by having job and economic development, rather than putting another clinic or any kind of health services out in the community.”My mother and I were relieved when we saw the family home on South Vernon still standing, and the building on South Wentworth perfectly intact. But a few relics and memories won’t save these communities that were the dream of generations of our ancestors who found their way out of the horrors of the Jim Crow South and hoped to start better lives — only now to have them cut short by longstanding discrimination, neglect and disinvestment.My mother turned 90 last year after our trip, and I am grateful for her long life — bolstered by leaving Chicago and spending her later years in more healthful environments. I looked back at the picture I took of her, standing in front of her elementary school on 60th and South Wabash Avenue, the building sagging with decay, and thought of not just what we left, but also what was lost.As my mother points to the stained bricks on the facade of her school building, the January wind churning dead leaves at her feet, I notice she’s standing under a towering and sturdy tree. Though it is stripped bare by the winter, its roots run deep in front of the faded school where Mom’s little-girl self roamed the halls sharing secrets with her friend Lorraine. I think of the people who remained, including my great-aunts and -uncles, and who still live in and around Bronzeville — and the hard effort and resilience it takes to survive and thrive in an environment that has been intentionally robbed of the resources our ancestors worked so hard to produce. I am reminded of the lines of another poem by Gwendolyn Brooks, who attended Englewood High School some years before my mother and Hansberry. In “The Second Sermon on the Warpland,” she writes: “It is lonesome, yes. For we are the last of the loud./Nevertheless, live./Conduct your blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.”Top photograph in opening photo illustration from the Chicago Housing Authority. Other photographs courtesy of the author.Linda Villarosa is a contributing writer for the magazine whose work focuses on race and health. She teaches journalism and Black studies at the City College of New York in Harlem.

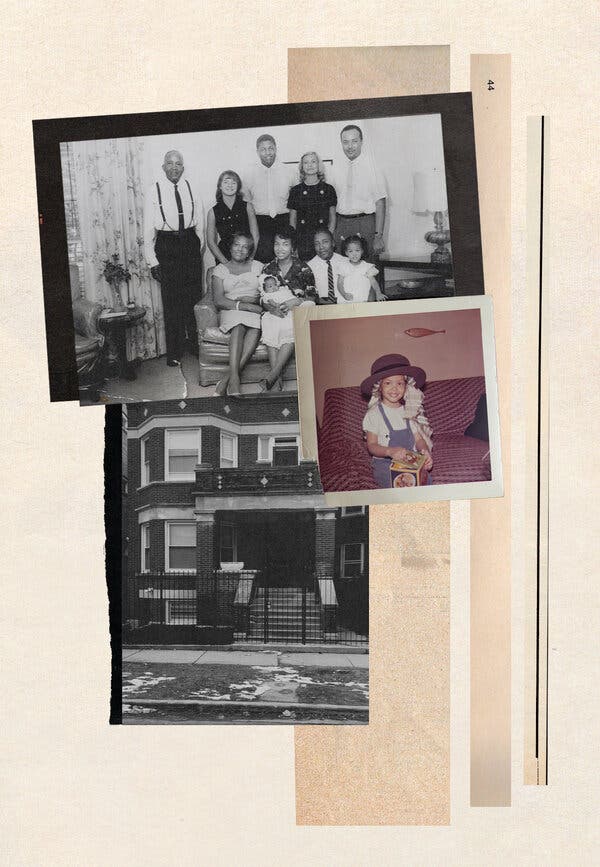

Read more →