Coronavirus: More work needed to rule out lab leak theory says WHO

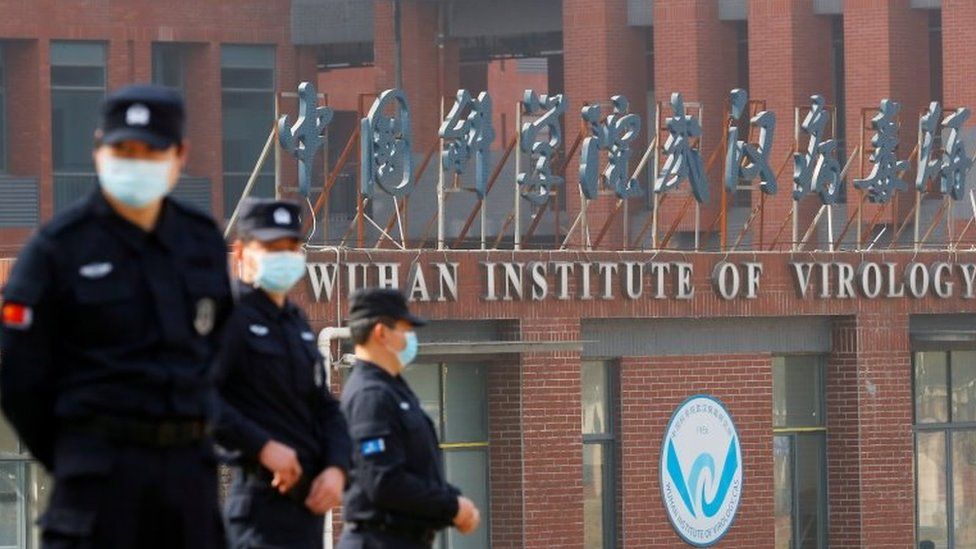

SharecloseShare pageCopy linkAbout sharingimage copyrightReutersThe head of the World Health Organization (WHO) says further investigation is needed to conclusively rule out a theory that Covid-19 emerged from a laboratory in China. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said on Tuesday that although a laboratory leak is the least likely cause, more extensive research is needed.The virus was first detected in Wuhan, in China’s Hubei province in late 2019.The Chinese government has dismissed the allegations of a virus leak.Since the novel coronavirus was first identified, more than 2.7 million people are known to have died from it, with more than 127 million cases worldwide.An international team of experts travelled to Wuhan in January to probe the origins of the virus. Their research relied on samples and evidence provided by Chinese officials. Dr Tedros said the team had difficulty accessing raw data and called for “more timely and comprehensive data sharing” in the future. image copyrightReutersThe team investigated all possibilities, including one theory that the virus had originated at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The institute is the world’s leading authority on the collection, storage and study of bat coronaviruses. Former US President Donald Trump was among those who supported the theory that the virus might have escaped from a lab.But a report by WHO and Chinese experts released on Tuesday and seen by AFP news agency, said the lab leak explanation was highly unlikely and the virus had probably jumped from bats to humans via another intermediary animal. Wuhan- City of silenceWuhan marks its anniversary with triumph and denialHowever the theory “requires further investigation, potential with additional missions involving specialist experts,” Dr Tedros said. “Let me say clearly that as far as WHO is concerned, all hypothesis remain on the table,” he added. Also on Tuesday, WHO investigation team leader, Peter Ben Embarek, said his team had found no evidence that any laboratories in Wuhan were involved in the outbreak. He added that his team had felt under political pressure, including from outside China but said he was never pressed to remove anything from the team’s final report.Dr Embarak added that it was “perfectly possible” that cases were circulating in the Wuhan area in October or November 2019. China informed the WHO about cases on 3 January, a month after the first reported infection. Shortly after, the US and 13 allies including South Korea, Australia and the UK, voiced concern over the report and urged China to provide “full access” to experts. The statement said the mission to Wuhan was “significantly delayed and lacked access to complete, original data and samples”.The group pledged to work together with the WHO. China has refuted claims the virus originated in a lab and says that although Wuhan is where the first cluster of cases was detected, it is not necessarily where the virus originated. State media has claimed that the virus may have arrived in Wuhan on frozen food imports.The country has largely brought its own outbreak under control through quick mass testing, stringent lockdowns and tight travel restrictions.

Read more →