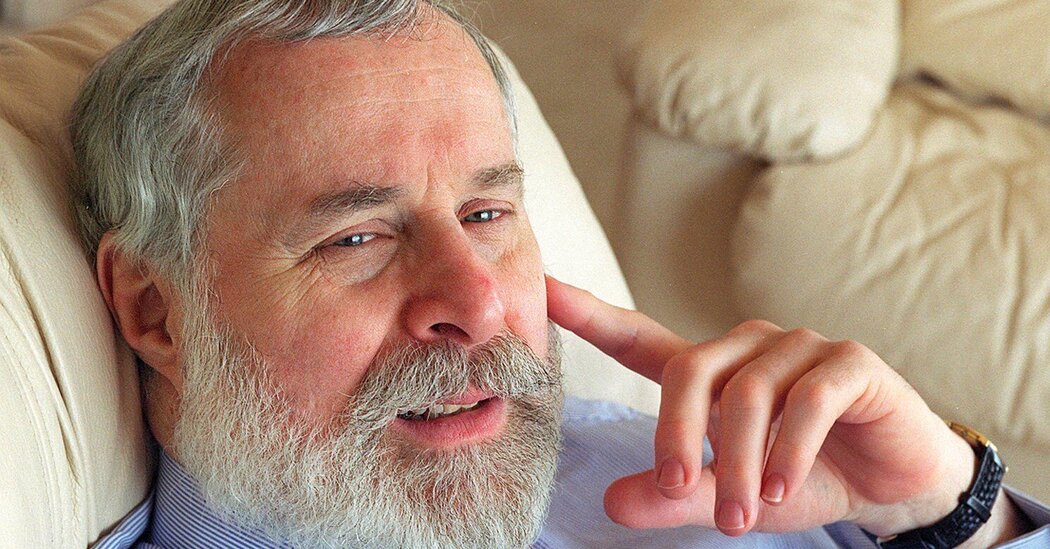

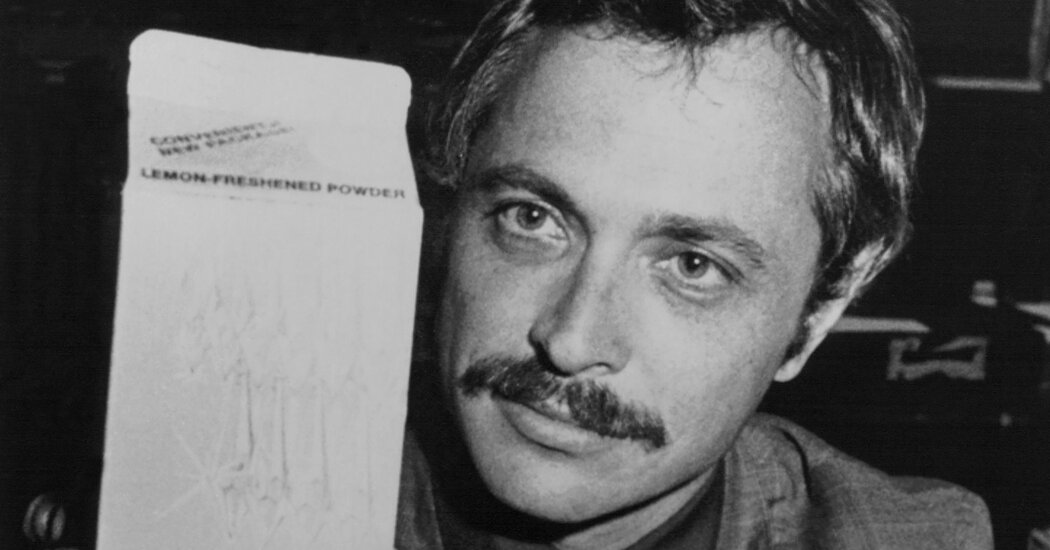

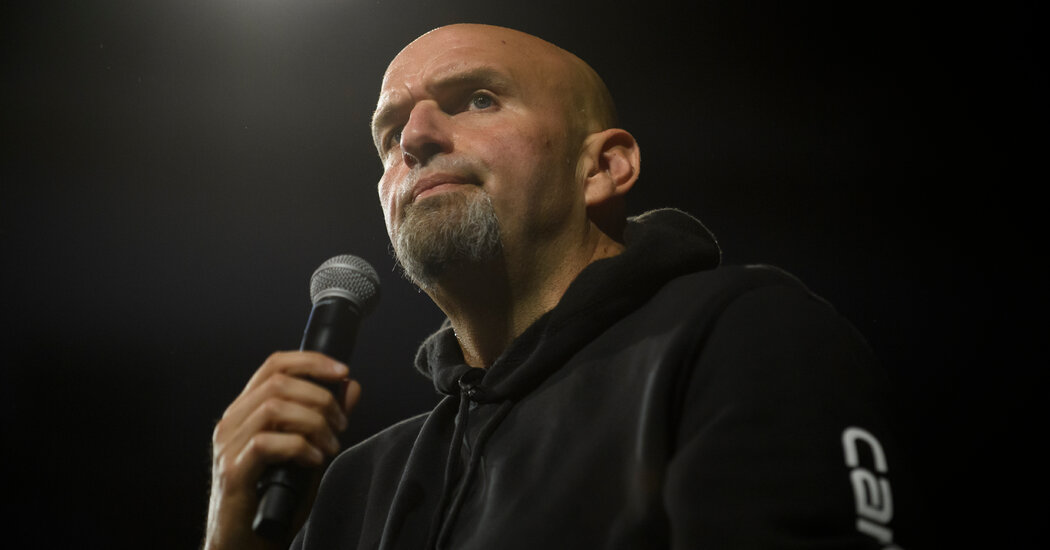

The celebrity physician, a candidate in Pennsylvania’s Republican primary for Senate, has a long history of dispensing dubious medical advice on his daytime show and on Fox News.A wealth of evidence now shows that the malaria drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine were not effective at treating Covid-19 and carried potential risks.But in the early months of the pandemic, Dr. Mehmet Oz, the celebrity physician with a daytime TV show, positioned himself as one of the chief promoters of the drugs on Fox News. In the same be-the-best-you tone that he used to promote miracle weight-loss cures on “The Dr. Oz Show,” he elevated limited studies that he said showed wondrous promise.His “jaw dropped,” he said, while reviewing one tiny study from France, calling it “a game changer.” In all, Dr. Oz promoted chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in more than 25 appearances on Fox in March and April 2020.When a Veterans Affairs study showed that Covid-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine were more likely to die than untreated patients, that advocacy came to an abrupt halt.“We are better off waiting for the randomized trials” that Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, had been asking for, Dr. Oz told Fox viewers.As Dr. Oz jumped last month into the Republican primary for Senate in Pennsylvania, where his celebrity gives him an important advantage in a crucial race, he tied his candidacy to the politics of the pandemic. He appealed to conservatives’ anger at mandates and shutdowns, and at the “people in charge” who, he said, “took away our freedom.”But the entry into the race of the Cleveland-born heart surgeon, a son of Turkish immigrants who has been the host of “The Dr. Oz Show” since 2009, also brought renewed scrutiny to the blemishes on his record as one of America’s most famous doctors: his long history of dispensing dubious medical advice.In ebullient language, he has often made sweeping claims based on thin evidence, which in multiple cases, like that of hydroxychloroquine, unraveled when studies he relied on were shown to be flawed.Over the years, Dr. Oz, 61, has faced a bipartisan scolding before a Senate committee over claims he made about weight-loss pills, as well as the opposition of some of his physician peers, including a group of 10 doctors who sought his firing from Columbia University’s medical faculty in 2015, arguing that he had “repeatedly shown disdain for science and for evidence-based medicine.” Dr. Oz questioned his critics’ motives and Columbia took no action, saying it did not regulate faculty members’ participation in public discourse.He has warned parents that apple juice contained unsafe levels of arsenic, advice that the Food and Drug Administration called “irresponsible and misleading.” In 2013, he warned women that carrying cellphones in their bras could cause breast cancer, a claim without scientific merit. In 2014, the British Medical Journal analyzed 80 recommendations on Dr. Oz’s show, and concluded that fewer than half were supported by evidence.Two researchers who worked on “The Dr. Oz Show” for a year during a break from medical school in the 2010s said in interviews that the show’s producers had originated most of its topics, often getting their ideas from the internet. But the researchers, whose job was to vet medical claims on the show, said that they had little power to push back, and that they regularly questioned the show’s ethics to one another and discussed quitting in protest.“Our jobs seemed to be endless fighting with producers and being overruled,” said one of the former researchers, both of whom are now physicians and insisted on anonymity because they said they feared that publicly criticizing him could jeopardize their careers.According to the former researchers, the show’s producers conjured an imaginary, typical viewer named “Shirley,” a woman whose children were grown and who had time to focus on herself. The standard advice for many ailments covered on the show — obesity, sluggishness, back pain — was exercise, the researchers said. But there was a quota on how often exercise could be mentioned.Shirley watched daytime TV and didn’t want to exercise, the researchers said they were told.Dr. Oz’s on-air medical advice on both his show and Fox News has taken on greater significance as he enters the political realm. His promotion of hydroxychloroquine grabbed President Donald J. Trump’s attention and contributed to early misinformation about the virus on the right.“Information can harm — that’s the key thing we need to appreciate here,” said Harald Schmidt, an assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. “His track record is pretty concerning. What we’ve seen so far does not instill confidence that this will help reasonable politics.”Dr. Oz, kneeling, rose to fame as a medical expert on Oprah Winfrey’s show.Jemal Countess/ Getty ImagesDr. Oz declined to to be interviewed for this article. His campaign manager, Casey Contres, said in a statement that the doctor had always put patients first and fought the “established grain” in medicine.“Dr. Oz believes it was truly unfortunate that Covid-19 became political and an excuse for the government and many in the corporate media to control the means of communication to suspend debate,” Mr. Contres added. “From the start, therapeutics meant to help with Covid-19 were regularly discounted by the medical establishment, and many great ideas were squashed and discredited.”Over the years, when pressed about offering unproven medical advice, Dr. Oz said his goal was to “empower” Americans to take control of their health. Grilled by senators in 2014 about false claims he made for weight-loss products, he said, “My job on the show, I feel, is to be a cheerleader for the audience.”He also said it was his right to use unscientific language. “When I feel as a host of a show that I can’t use words that are flowery,” he told the senators, “I feel like I’ve been disenfranchised, like my power’s been taken away.”In using the politics of the pandemic to shape his campaign for an open seat — one pivotal to Senate control in the midterms — Dr. Oz may be in tune with primary voters in Pennsylvania. The race has drawn candidates echoing Mr. Trump’s lie that the 2020 election was stolen, including Jeff Bartos, a developer, and Carla Sands, a former ambassador. David McCormick, a hedge-fund executive married to a former Trump administration official, is expected to join the field soon.The criticism Dr. Oz has received over the years for spreading misinformation has done little to tarnish his celebrity, as measured by his long-running TV program, whose distributor announced that the show would end in January when its host departs.Still, misinformation about the coronavirus emanating from the Trump White House and conservative news sites helped politicize the nation’s response to the pandemic, with deadly consequences in many Republican areas of the country.Although Dr. Oz spoke strongly in favor of masks and vaccines on Fox, his championing of unproven treatments early on sharply contradicted infectious-disease experts like Dr. Fauci who urged caution.In Pennsylvania, as around the country, counties that voted by large margins for Mr. Trump in 2020 have had lower vaccination rates and higher death rates from Covid than counties that voted heavily for President Biden.Yet at one point early in the pandemic, he said that reopening schools was an “appetizing opportunity” that might cause the deaths of “only” 2 to 3 percent of the population. He later walked back the statement.“I can’t believe he took the same oath that I did when we graduated,” said Dr. Val Arkoosh, an anesthesiologist and county official in the Philadelphia suburbs who is running in the Democratic primary for Senate. “That oath is about first doing no harm and always putting your patients first. I just think he’s a quack, to be honest.”In reply to Dr. Arkoosh, Mr. Contres said that Dr. Oz had performed thousands of heart surgeries and had “helped countless patients live a better life.”Dr. Oz testifying before the Senate subcommittee on consumer protection in 2014, when senators pressed him on claims he had made about weight-loss pills.Tom Williams/CQ Roll CallIn Dr. Oz’s 2014 appearance before the Senate subcommittee on consumer protection, Claire McCaskill, then a Democratic senator from Missouri, quoted a bit of his TV sales patter back to him: “You may think magic is make-believe, but this little bean has scientists saying they’ve found the magic weight-loss cure for every body type — it’s green coffee extract.”Dr. Oz admitted to the senators that his claims often “don’t have the scientific muster to present as fact.” A study he had cited about green-coffee bean extract was later retracted and described by federal regulators as “hopelessly flawed.” The supplier of the extract paid $3.5 million to settle charges by the Federal Trade Commission.Dr. David Gorski, a surgery professor at Wayne State University and longtime critic of alternative medicine, said Dr. Oz’s emergence as a Fox News authority on the coronavirus was no surprise him.“He could have gone the route of trying to be more reasonable and careful, vetting information, trying to reassure people where the science was still unsettled,” Dr. Gorski said. “But of course, that wouldn’t be Dr. Oz’s brand.”Early in the pandemic, on March 20, 2020, Dr. Oz appeared on several Fox News shows trumpeting what he called “massive, massive news” — a small study by a divisive French researcher, Dr. Didier Raoult, who claimed a 100 percent cure rate after treating coronavirus patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, or Z-Pak. At the time, with Covid-19 cases and deaths rising rapidly, hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial treatment, was being studied in multiple countries and adopted by hospitals without much evidence. Mr. Trump hyped it repeatedly at White House news conferences as part of his effort to minimize the crisis. Dr. Oz communicated with Trump advisers about speeding the drug’s approval to treat Covid. On March 28, the F.D.A. authorized its emergency use. On Fox, Dr. Oz noted that the Raoult study, with just 36 participants, was not a clinical trial, but his enthusiasm overran his caution. The study was the “most impressive bit of news on this entire pandemic front,” he gushed. On April 1, as Dr. Oz called on Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York to lift restrictions on hydroxychloroquine, a public health expert, Dr. Ashish Jha of Brown University, cautioned Fox viewers that “the facts are just not in” on the drug.There was much confusion in the early days of the crisis about how the virus spread and how to slow it, with some expert views reversed by new information. The Raoult study quickly fell apart. Only six patients had received the two-drug combination, all with mild or early infections. One who was reported “virologically cured” on Day 6 was found to have the virus two days later. Six other patients treated only with hydroxychloroquine were omitted from the final results, including one who died and three others who were transferred to intensive care.On April 3, the board of the research journal that initially published the study said it did not meet the “expected standard.” In June 2020, the F.D.A. revoked emergency authorization of hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19. That November, the National Institutes of Health concluded that the drug held no benefit in treating Covid-19.By then, Dr. Oz’s once-daily appearances on Fox had tapered off. He was rarely seen on the network this year. But he returned to Sean Hannity’s show on Nov. 30 to announce his candidacy, seizing the opportunity to push back at critics of his medical career.“Doctors are about solutions,” he said. “But instead, people with good ideas are shamed, they’re silenced, they’re bullied, they’re canceled.”Susan C. Beachy

Read more →