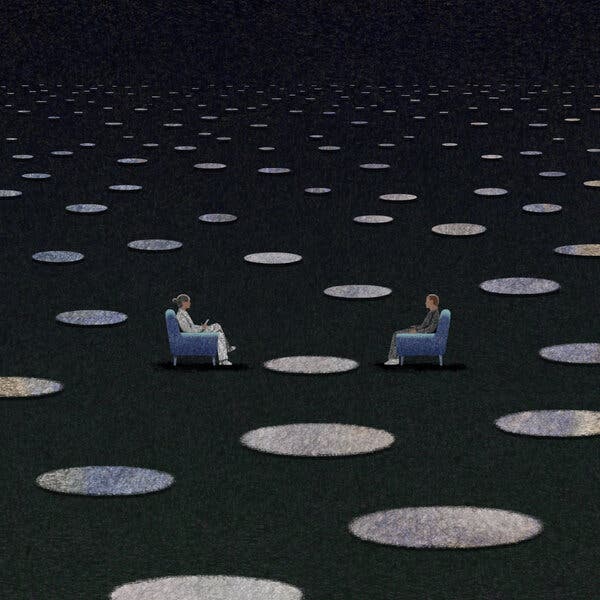

Listen to This ArticleAudio Recording by AudmIn my late 20s, living alone in New York, I found myself in the grip of a dark confusion, unclear of how to proceed — and so I started seeing a therapist. During most visits, I sat in a chair with a box of tissues on the small table beside it, but the office also held a couch, on which I occasionally reclined, staring at the ceiling as I wrestled with what I was doing with my life, and even what I was doing in that office. Back then, therapy was still perceived in some circles as a rarefied recourse for the irredeemably neurotic. I was embarrassed that I seemed to need it, and I could hardly afford the expense. It ate up so much of my pay that I sometimes daydream about the little house in the Catskills that I might now enjoy had I invested the money I spent on those twice-weekly sessions in any reputable mutual fund instead. Were they worth it? I know therapy provided me comfort, and I believe I developed some self-awareness, which has served me well. But during that phase of my life, I also spent more time than I should have, I’m sure, in a patently unhealthful relationship that my therapist and I endlessly discussed, as if it were a specimen to be dissected rather than discarded.Whatever my ambivalence about therapy, I trusted it enough to return to it several times, trying other modes that have become increasingly popular, including two versions of cognitive-behavioral therapy. More recently, I explored a form of therapy that had me locating my feelings in particular parts of my body so that I could — oh, I don’t know what, although I recall that I found it interesting at the time. Over the decades, and especially since the pandemic, the stigma of therapy has faded. It has come to be perceived as a form of important self-care, almost like a gym membership — normalized as a routine, healthful commitment, and clearly worth the many hours and sizable amounts of money invested. In 2021, 42 million adults in the United States sought mental-health care of one form or another, up from 27 million in 2002. Increasingly, Americans have bought into the idea that therapy is one way they can reliably and significantly better their lives. As I recently considered, once again, entering therapy, this time to adjust to some major life transitions, I tried to pinpoint how exactly it had (or had not) helped me in the past. That train of thought led me to wonder what research actually reveals about how effective talk therapy is in improving mental health. Occasionally I tried to raise the question with friends who were in therapy themselves, but they often seemed intent on changing the subject or even responded with a little hostility. I sensed that simply introducing the issue of research findings struck them as either threatening or irrelevant. What did some study matter in the face of the intangibles that enhanced their lives — a flash of insight, a new understanding of an irrational anger, a fresh recognition of another’s point of view? I, too, have no doubt that therapy can change people’s lives, and yet I still wanted to know how reliably it offers actual relief from suffering. Does therapy resolve the symptoms that cause so much pain — the feeling of dread in people who deal with anxiety, or insomnia in people who are depressed? Does the talking cure, in fact, cure? And if it does, how well? Sigmund Freud, the brilliant if dogmatic father of psychoanalysis, was famously uninterested in submitting his innovation to formal research, which he seemed to consider mere bean-counting in the face of his cerebral excavations of the unconscious. Presented with encouraging research that did emerge, Freud responded that he did not “put much value on these confirmations because the wealth of reliable observations on which these assertions rest make them independent of experimental verification.” A certain skepticism of the scientific method could be found in psychoanalytic circles well into the late 20th century, says Andrew Gerber, the president and medical director of a psychiatric treatment center in New Canaan, Conn., who pursued the use of neuroimaging to research the efficacy of therapy. “At my graduation from psychoanalytic training, a supervising analyst said to me, ‘Your analysis will cure you of the need to do research.’”Over time, formal psychoanalysis has largely given way to less-libido-focused talk therapies, including psychodynamic therapy, a shorter-term practice that also focuses on habits and defenses developed earlier in life, and cognitive-behavioral therapy, which helps people learn to replace negative thought patterns with more positive ones. Hundreds of clinical trials have now been conducted on various forms of talk therapy, and on the whole, the vast body of research is quite clear: Talk therapy works, which is to say that people who undergo therapy have a higher chance of improving their mental health than those who do not. That conviction gained momentum in 1977, when the psychologists Mary Lee Smith and Gene V. Glass published the most statistically sophisticated analysis on the subject until that point. They looked at some 400 studies in a paper known as a meta-analysis — a term Glass coined — and found that among the “neurotics” and “psychotics” who had undergone various kinds of talk therapy, the typical patient fared better than 75 percent of those with similar diagnoses who went untreated. The finding that therapy has real benefits was replicated numerous times in subsequent years, in analyses applied to patients with anxiety, depression and other prevalent disorders.“I think the evidence is fairly clear that psychotherapy is remarkably effective,” says Bruce Wampold, a prominent researcher in the field who is an emeritus professor of counseling psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. To him, the power of such a low-tech treatment is nothing short of miraculous, especially given that studies typically follow patients for 20 sessions or fewer: “The fact that you can just go talk to another human being — I mean, it’s more than just talking — and get effect sizes that are measurable, and remarkably large?” Wampold is best known for research suggesting that all types of evidence-based talk therapies work equally well, a controversial phenomenon known as the Dodo Bird effect. (The effect takes its name from the Dodo in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” who, when asked to judge a race, decrees, “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes!”) Hash out your childhood with a psychodynamic therapist, write down probabilities of feared outcomes with a cognitive-behavioral therapist, work on your boundaries with an interpersonal therapist — they will all yield equally positive results, found Wampold and others who have replicated his work. But there are reasons to think that this picture of therapy overpromises. As is true of much research, studies with less positive or striking results often go unpublished, so the body of scholarly work on therapy may show inflated effects. And researchers who look at different studies or choose different methods of data analysis have generated more conservative findings. Pim Cuijpers, a professor of clinical psychology at Vrije University in Amsterdam, co-wrote a 2021 meta-analysis confirming that therapy was effective in treating depression compared with controls, but he also found that more than half of the patients receiving therapy had little or no benefit and that only a third entered “remission” (meaning their symptoms lessened enough that they no longer met the study’s criteria for depression). Given that the patients were assessed just one to three months after treatment started, Cuijpers said he considered those results “a good success rate,” but he also noted that “more effective treatments are clearly needed” because so many patients did not meaningfully benefit. A blunter assessment of short-term therapies appears in a 2022 paper published by Falk Leichsenring and Christiane Steinert, psychotherapists and researchers affiliated with universities in Germany, who surveyed studies comprising some 650,000 patients suffering from a broad range of mental illnesses. “After more than half a century of research” and “millions of invested funds,” they wrote, the impact that therapy (and medication, for that matter) had on patients’ symptoms was “limited.”Such different interpretations of the data persist in part because of some of the field’s particular research challenges, starting with what constitutes a suitable control group. Many researchers put half the people who sign up to participate in a trial on a waiting list, in order to use that cohort as a control group. But critics of that method argue that languishing on a waiting list puts patients in an uncomfortable state of limbo, or makes them less likely to seek help from other sources, thus inflating the difference between their well-being and the well-being of those who received care. Other researchers try to provide a control group by offering a neutral nontherapy therapy, but even those are thought to have some placebo effect, which could make the effect of therapy look smaller than it really is. (One researcher, in trying to devise a neutral form of therapy to serve as a control, even managed to stumble on a practice that improved patients’ well-being about as well as established therapies.) So the debate continues, not just about the extent of therapy’s effectiveness but about the notion of the Dodo Bird effect. Many proponents of cognitive-behavioral therapy insist on the superiority of their approach for the treatment of depression and anxiety by pointing to competing meta-analyses. David Tolin, director of the Anxiety Disorders Center at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Conn., wrote one such meta-analysis. “Cognitive-behavioral therapy has a small to medium advantage over psychodynamic therapy,” he says. Nonetheless, he finds the measured results of cognitive-behavioral therapy to be unsatisfying, in his own research and in others’. He points to another meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy and anxiety disorders that found that only 50 percent of patients responded to the treatment. “It is not what I would call a home run,” he told me. Tolin has started to wonder if it’s time for research to shift away from talk therapy toward more innovative strategies. Leichsenring, too, has called for a “paradigm shift” in order to make further progress. For depression, there’s some evidence that therapy plus psychiatric medications is more effective than therapy or medication alone. Tolin believes that researchers should be focusing more attention on drugs that work in novel ways, such as one that has been shown to stimulate the same neurons that are active during cognitive-behavioral therapy. “Maybe we have reached the limit of what you can do by talking to somebody,” Tolin says. “Maybe it’s only going to get so good.” Illustration by Dadu ShinEllen Driessen is a psychologist in the Netherlands who believes, to the contrary, that the field has not yet unlocked the full potential of talk therapy. Driessen’s Twitter bio describes her as a “passionate depression treatment researcher,” and she has devoted herself in recent years to finding ways to maximize therapy’s effectiveness. Her goal: to determine which kinds of therapies work best for which kinds of patients, in the hope that those targeted pairings will yield better results. In her own practice, when patients turn to her for guidance about what treatment to choose, she often feels frustrated by uncertainty. The finding that all types of therapy work equally well, Driessen believes, could be hiding the variation that exists from person to person. Given the state of research, it is impossible to know what to recommend for an individual patient. “I don’t know which of these treatments will work best for you,” she resorts to saying. “And that is something that I, as a clinician, find very unsatisfying.”Most studies do not break down the results of various psychotherapies by type of patient — by gender, for example, or comorbidities, or age of onset of illness. The trials are too small to generate statistically meaningful results for those categories. Driessen and colleagues are undertaking the ambitious task of going back to the researchers on at least 100 trials to procure identifying details about patients, so that their samples will be large enough to allow them to determine whether certain kinds of people are more likely to respond to one kind of therapy or another. The project will most likely be underway for a decade before they can tease out matches between practice and patient. Another growing school of research, meanwhile, hopes to move practitioners away from adhering strictly to one school or another, by identifying the most effective components of each — the practice of exposing patients to the sources of their fears, for example, or examining relationship patterns. But Wampold believes that eventually these researchers will simply land, with their collection of techniques, on yet another form of therapy that proves about as effective as all the others. The most significant difference in patient outcomes, Wampold says, almost always lies in the skills of the therapist, rather than the techniques they rely on. Hundreds of studies have shown that the strength of the patient-therapist bond — a patient’s sense of safety and alignment with the therapist on how to reach defined goals — is a powerful predictor of how likely that patient is to experience results from therapy. But what distinguishes the therapists most likely to forge those bonds is not intuitive. Wampold says that some of the attributes that would seem most salient — a therapist’s agreeability, years of training, years of experience — do not correlate at all with effectiveness of care. To demonstrate the skills that do correlate, Timothy Anderson, director of the Psychology & Interpersonal Process Lab at Ohio University, studied groups of therapists who have been rated by patients as highly effective. He put them through a monitored exercise in which they were asked to respond to video clips featuring actors playing out difficult situations that commonly arise in therapy. “The patient might be saying, ‘This isn’t working — you can’t help me,’” Anderson says. He found that the highest-rated therapists tended, in those moments, to avoid responding with hostility or defensiveness, but instead replied with a pairing of language and tone that fostered a positive bond. “That’s displayed by the therapist saying things like, ‘We’re in this together,’” Anderson told me, “even when the patient is saying, ‘You can’t help me no matter what.’” Among the other qualities that these therapists displayed were verbal fluency — the ability to speak clearly in ways the patient could quickly grasp — along with an ability to persuade the patient and to focus on a specific problem. A certain humility in the face of the field’s uncertainties also seems to help; on a different questionnaire, therapists whose care was more successful gave responses that “reflected self-questioning about professional efficacy in treating clients.” For the past four years, Anderson says, he has been running workshops that aim to train therapists in these various skills. “Can we do it in brief workshops?” he says. “I’m not sure that we can.” Empathy, a capacity for alliance building — these might be innate, elusive, alchemic gifts that are challenging to teach. Anderson believes that people who become therapists tend to have more of those qualities than the general population, but he also referred to a study from the 1970s suggesting that laypeople who naturally have those skills performed nearly as well in therapeutic simulations as trained therapists with Ph.D.s. Is the idea, I asked Anderson, that patients should seek out therapists with whom they personally connect? That, just as most happy couples are made up of people who failed in previous relationships, the challenge lies in finding the right chemistry? Or is it more absolute? That perhaps some therapists are universally gifted at forging those bonds and can do so effectively with almost any patient. “They could both be true,” Anderson said. The answer struck me as yet another frustrating unknown in the field. I had perhaps — as a longtime consumer of therapy in search of reassurance — hit my limit with the disputes among the various clinicians and researchers, the caveats and the debates over methodology. “The research seems very … baggy,” I said, not bothering to hide my frustration. “It’s not very satisfying.” I could practically hear a smile on the other end of the phone. “Well, thank you,” Anderson said. “That’s what makes this research so interesting. That there are no simple answers, right?” A handful of well-chosen words — and I felt soothed, even touched by his positivity, which included, with that question mark at the end of his sentence, a hint of inclusiveness. Confronted with my clear annoyance, he had offered me a nondefensive, constructive and positive response. We were in this together. The exchange made me think of the best hours I have spent in therapy, times when I felt the depth of a therapist’s caring, or experienced the reframing of a particular thought that I hadn’t even known could be cast in so different a light. The therapist Stephen Mitchell has described therapy as a “shared effort to understand and make use of the pains and pleasures of life’s experiences.” Therapy, in his language, is not a practice that tries to fix any one thing, but one that aspires to help its participants build the most out of the challenges that face them. Jonathan Shedler, a psychodynamic psychologist and vocal critic of the research on therapy, believes that the field, in its narrow focus on reducing symptoms, fails to capture other ways patients benefit from psychodynamic therapy. “It’s not a fair comparison to look at how they’re doing the day therapy ends,” he says. “We’re aiming to go farther — to change something fundamental, so that people can feel more at peace with themselves and have more meaningful connections with others.”Anderson and I had set aside a half-hour to talk about therapist skills, and as the minutes passed, I felt that familiar sensation of the clock ticking, even as I wished he and I could keep talking — there was so much to discuss. Alas, he gently conveyed, our time was up.Dadu Shin is an illustrator in Brooklyn who has worked for clients like The New York Times and Armani Exchange. His work focuses on emotion and empathy.

Read more →