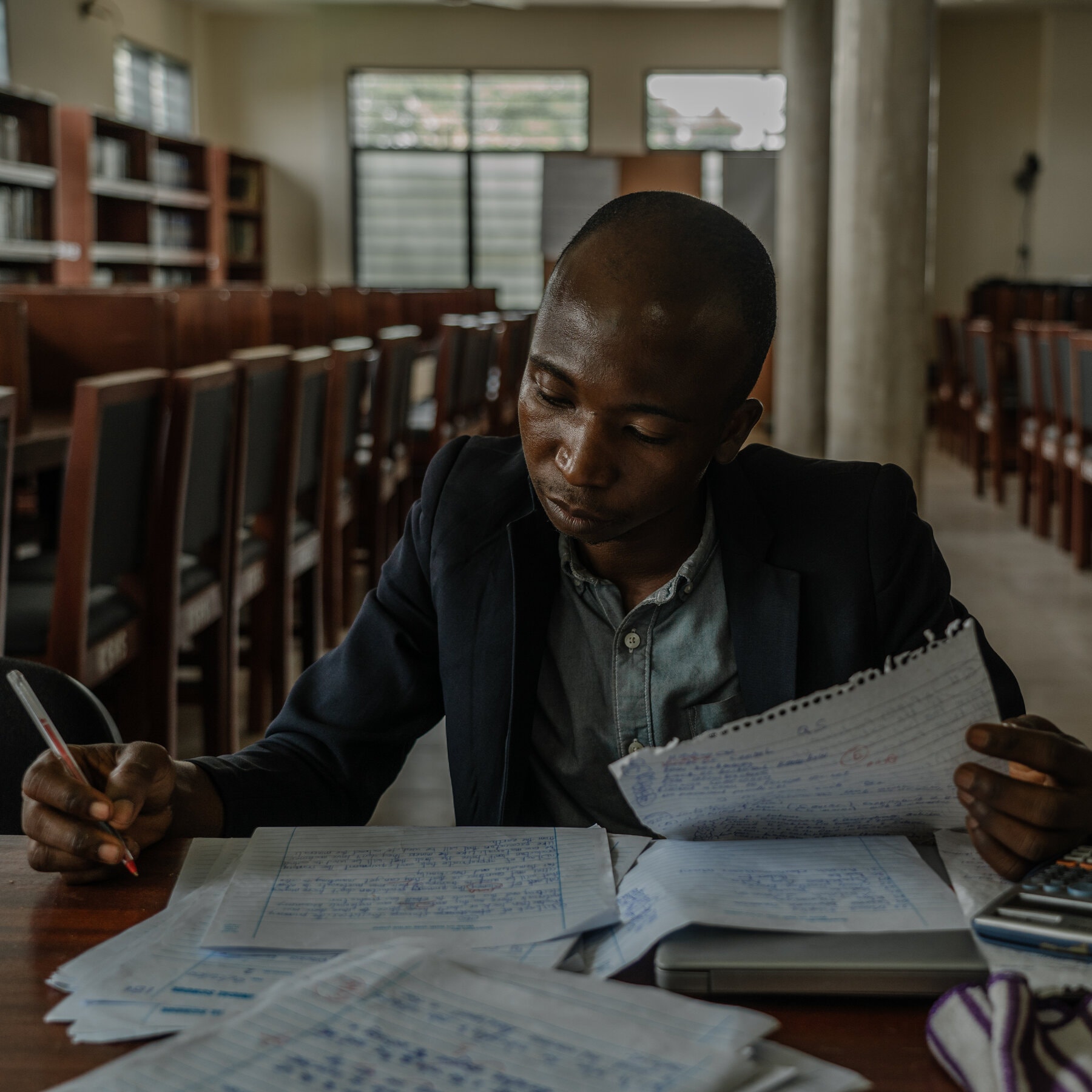

At Kaneshie Polyclinic, a health center in a hardscrabble neighborhood of Accra, the capital of Ghana, there is a rule. Every patient who walks through the door — a woman in labor, a construction worker with an injury, a child with malaria — is screened for tuberculosis.This policy, a national one, is meant to address a tragic problem; two-thirds of the people in this country with tuberculosis don’t know they have it.Tuberculosis, which is preventable and curable, has reclaimed the title of the world’s leading infectious disease killer, after being supplanted from its long reign by Covid-19. But worldwide, 40 percent of people who are living with TB are untreated and undiagnosed, according to the World Health Organization. The disease killed 1.6 million people in 2021.The numbers are all the more troubling because this is a moment of great hope in the fight against TB: Significant innovations in diagnosing and treating it have started to reach developing countries, and clinical trial results show promise for a new vaccine. Infectious disease experts who have battled TB for decades express a new conviction that, with enough money and a commitment to bring those tools to neglected communities, TB could be nearly vanquished.“This is the best news we’ve seen in tuberculosis in decades,” said Puneet Dewan, an epidemiologist with the TB program at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “But there’s a gap between having an exciting pipeline and actually reaching people with those tools.”A recent visit to the Kaneshie clinic revealed both the progress and the remaining barriers. Despite the clinic’s policy of screening everyone for TB, which most often attacks the lungs, by asking a few questions about coughs and other symptoms, patients streamed into the single-story, cement-block building and were sent for care without any such queries. A member of the TB team, it turned out, was on holiday, another was on maternity leave and a third was out sick. That left just two, who were busy processing tests and doling out drugs.So no one was screened, not that day or any other day in the previous week.“It is a good policy, it works well when we can do it, but personnel is a problem,” said Haphsheitu Yahaya, the tuberculosis coordinator at the clinic.Richard Wonu, a radiographer, examined scans at the Kaneshie Polyclinic.A laboratory at the clinic.When the screening policy is working, new medications — the first to come to market since the 1970s — can be taken as just a couple of pills each day, rather than as handfuls of tablets and painful injections, the way TB treatments have been delivered in the past.Those diagnosed with drug-resistant TB receive medication to take for six months — a far shorter time than previously required. For decades, the standard treatment for drug-resistant TB was to take drugs daily for a year and a half, sometimes two years. Inevitably, many patients stopped taking the medicines before they were cured and ended up with more severe disease. The new drugs have far fewer onerous side effects than older medications, which could cause permanent deafness and psychiatric disorders. Such improvements help more people to continue taking the drugs, which is good for patients, and eases the strain on a fragile health system.In Ghana and most other countries with a high prevalence of TB, the drugs are paid for by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, an international partnership that raises money to help countries fight the diseases. But contributions to the agency have been getting smaller with each funding round. Countries fighting TB are concerned about what may happen if that funding ends. Currently, the treatment for adults recommended by the W.H.O. costs at least $150 per patient in low- and middle-income countries.“If our patients had to pay, we would not have one single person taking treatment,” Ms. Yahaya said.Still, there has been progress in recent months in making the medicines more affordable, and prices may soon drop further. After prolonged pressure from patient advocacy groups, the United Nations and even the novelist John Green, who devoted his widely followed TikTok account to the issue, Johnson & Johnson has lowered the price of a key TB drug in developing countries. The company also agreed last month not to enforce a patent, which means generic drug companies in India and elsewhere will be able to make a significantly cheaper version of the medication.Richard Boadi, center, a nurse at the clinic, took notes on a possible tuberculosis case.A patient’s sputum sample was prepared for analysis.And for the first time in more than a hundred years, there is real hope for an effective vaccine: A promising candidate called M72, developed by the pharmaceutical company GSK with financial backing from the Gates Foundation and other philanthropies, is now in the last stage of clinical trials.(However, as ProPublica recently reported, it’s not clear who will have the rights to sell the vaccine, where it will be available and how much it will cost. Taxpayer and philanthropic money has paid for much of the vaccine’s development, but GSK retains control of critical components.)M72 is one of 17 vaccine candidates that are currently being tested in trials, providing a wellspring of possibilities. The only TB vaccine in use today was first given to people in 1921; it is helpful primarily for babies and does little to protect adolescents and adults, who account for more than 90 percent of TB transmission globally.Better technology to diagnose TB is slowly reaching clinics in developing countries. Clinics across South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, including the one in Ghana, now have machinery to use rapid molecular diagnostic tests — equipment that was donated as part of the Covid response. That means that many health centers have finally stopped using an unreliable diagnostic method, developed in the 1800s, of viewing sputum smears under microscopes.Still, in 2021 only 38 percent of people diagnosed with TB were first given a molecular test; the rest were diagnosed with a microscope, or, in many cases, by their clinical symptoms.The molecular diagnosis can also spot drug-resistant TB right away. (The old method involved starting a person on a course of the most common drugs and waiting to see whether the treatment worked; if patients had the drug-resistant form of the disease, they just got sicker.)Joshua Dodoo, a driver, came to Kaneshie clinic in March with a lingering cough. He had been shedding pounds and couldn’t sleep. When he saw a doctor for what he thought was malaria, he was sent for a TB test. The one PCR machine in the clinic’s lab was in heavy use, so it was a few days before he learned from a nurse that he had TB.“I was so frightened,” Mr. Dodoo said, adding that he had not realized people still caught the disease.Mr. Boadi, left, gave instructions on how to use a sputum sample cup to Sadia Ribiro, center, and her husband, Joshua Dodoo, so that they could test their youngest child for TB.Mr. Dodoo’s and Ms. Ribiro’s children both developed coughs since their father was diagnosed with TB this year.His wife, Sadia Ribiro, was calmer and able to hear the nurse, Richard Boadi, explain that there is a cure, and that Mr. Dodoo would be given the treatment for free. Ms. Ribiro was tested; people living in close contact with a person who has TB account for a significant percentage of the 10.6 million new infections each year. She was negative, and was put on a course of preventive drugs for three months. These medications are new, too: Until recently, preventive therapy could take a year or more, and few patients finished it.But then, the system broke down. The couple’s two children, who are 3 and 11, were not screened. Mr. Dodoo said they were in school so it was difficult to bring them to the clinic, and they had seemed healthy. Then, even as he started regaining weight and feeling better, the children started coughing and complaining of fatigue.But they didn’t get a test until months later, when Mr. Boadi tracked then down at home. Only 30 percent of TB infections in children are diagnosed.Ms. Yahaya, the clinic director, said that, while preventive therapy worked remarkably well, the experience of Mr. Dodoo’s family was typical. People who are newly diagnosed don’t want anyone to know that they have the disease, which is associated with poverty and suffering, so they don’t volunteer information about other people who may have been infected. And the understaffed health system struggles to track them.Only 169 health centers across Ghana have the capacity to use the new testing method. Usually, samples must be sent away — up to a three-hour drive in some rural areas. By the time results come in, it can be hard to track down those who were tested.“The equation is simple: If we were putting more resources into testing for TB, we would be finding more TB,” said Dr. Yaw Adusi-Poku, who heads Ghana’s national TB control program.Ms. Gyan, a TB patient, picked up her drugs from the clinic. That will require more molecular testing sites, more staff members trained to spot the disease, more people to ask questions at the clinic door, more nurses like the intrepid Mr. Boadi, who turns up at his patients’ doors to encourage them to have their families tested (and who frequently digs into his own pocket to help patients pay for bus fare to pick up their drugs).Molecular diagnosis is considerably more expensive than the old method. Cepheid, the company that makes cartridges for the testing machines, recently agreed to cut the price of each one to $8 from $10. An analysis commissioned by Doctors Without Borders found that the cartridges could be made for under $5. Cepheid continues to charge $15 per test for the diagnosis of extremely drug-resistant TB, the most lethal form of the disease.Funding for TB services in low- and middle-income countries fell to $5.8 billion in 2022 from $6.4 billion in 2018, which is just half of what the W.H.O. says is needed. About $1 billion is available each year for TB research, half the amount that the United Nations says is required.At a special meeting on TB at the United Nations last month, governments committed to spending at least $22 billion a year on TB by 2027. But at a similar meeting in 2018, the same donors promised to spend $13 billion by 2022, less than half of which materialized.“I’m happy that we have these innovations, but the fact that they exist, that the W.H.O. recommends them, doesn’t mean people have access to them,” said Dr. Madhukar Pai, who leads the McGill International TB Centre at McGill University in Montreal. “The costs are still too high, and you need someone to deliver them.”

Read more →