Former Heads of State Call on U.S. to Commit $5 Billion for Global Covid Aid

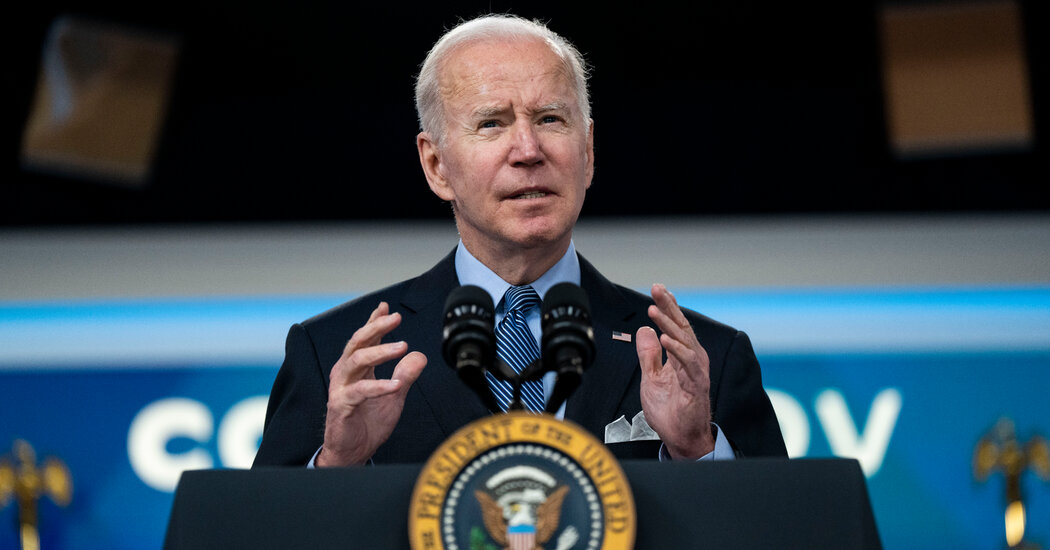

A group of former heads of state and Nobel laureates are calling on the United States to immediately commit $5 billion to combat the global coronavirus pandemic, and activists are pressing President Biden to take a more forceful leadership role in the response as he convenes world leaders for a Covid-19 summit on Thursday.“I want America to recognize that the disease is not over anywhere until it’s over everywhere,” Gordon Brown, the former British prime minister, who is leading the push for funding, said in an interview Monday, adding, “We must not sleepwalk into the next variant.”But Mr. Biden conceded Monday afternoon that “much needed funding” for the Covid-19 response is not coming anytime soon. In a statement issued by the White House, the president said he had been informed by congressional leaders in both parties that including the funding in a new aid package for Ukraine would “slow down action on the urgently needed Ukrainian aid,” and that he was resigned to having the two packages move separately.“However let me be clear: As vital as it is to help Ukraine combat Russian aggression, it is equally vital to help Americans combat Covid,” Mr. Biden wrote, adding that both the domestic and the global response would suffer if the funding is not approved.Mr. Biden has asked Congress to authorize $22.5 billion in emergency coronavirus aid, including $5 billion for the global pandemic, but the request has stalled on Capitol Hill. A compromise proposal for $10 billion in emergency aid includes no money for the global response, meaning Mr. Biden will almost certainly arrive at his own summit empty-handed. Mr. Brown said in the interview that his appeal is intended to place pressure on Congress to release the funds.The White House said Monday that Mr. Biden will address the summit, and that Vice President Kamala Harris and Dr. Ashish K. Jha, the coronavirus response coordinator will also participate. Both Dr. Jha and Mr. Biden have been working behind the scenes to press lawmakers to authorize the funding, officials said.The summit, a virtual gathering that will be co-hosted by Belize, Germany, Indonesia and Senegal, is aimed at reinvigorating the global response. The need is urgent: The drive to vaccinate the world is losing steam; testing has plummeted around the globe and efforts to bring tests and Covid antiviral pills to low- and middle- income nations are stalled, running into obstacles that recall battles fought 20 years ago around H.I.V.Mr. Brown, now the World Health Organization’s ambassador for global health financing, said he is also encouraging leaders of other wealthy nations to make funding commitments. He is the lead author on a letter to the president whose signatories also include Mary Robinson, a former president of Ireland; Helen Clark, a former prime minister of New Zealand; and Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize-winning economist.“Mr. President — your leadership can revive the global Covid-19 response,” they wrote, adding that “our wholehearted hope is that your administration will step up to provide leadership on financing the global response, encouraging other countries to follow you, as is both urgent and necessary to help save lives across the world.”Global health officials are increasingly concerned about what many are calling “Covid fatigue,” as world leaders deal with crises like the war in Ukraine, or turn to other pressing health concerns.“Donors are predominantly saying, ‘Oh, we want to get back to, you know, whatever it was that they prefer funding like maternal child health, H.I.V., T.B., whatever it is, and they’re saying that there’s a reduced appetite for Covid,” said Dr. Fifa A. Rahman, an adviser to ACT-Accelerator, the consortium backed by the W.H.O. that is leading the global response.The summit is a follow-up to one Mr. Biden convened in September; he will use the gathering to ask wealthy nations to step up their financial contributions for vaccines, tests and treatments. Specifically, he will call on developed nations to donate $2 billion to purchase Covid treatments and $1 billion to purchase oxygen supplies for low- and middle-income countries, according to a senior administration official involved with the planning.The United States, working with international organizations, has donated more vaccine doses than any other nation to the global vaccination effort. Mr. Biden has pledged 1.2 billion doses to other nations; as of Monday, more than 539 million had been shipped, according to the State Department. But countries receiving the doses have had difficulty getting those shots into arms.Activists and advocacy groups are increasingly impatient. Organizations including Public Citizen, the consumer health and safety nonprofit; Prep4All, an AIDS advocacy group; and HealthGAP, a global health advocacy group that operates in Uganda, are circulating a petition that blasts the United States government — though not Mr. Biden personally — for a “lack of leadership” that “is alarming and shortsighted.”The petition urges the president to “act with reinvigorated urgency” and lays out specific demands, including working with international institutions and donor countries to “mobilize $48 billion this year to get the global response on track” and pressing drugmakers to share their intellectual property and technological know-how, not only for vaccines but also for Covid antivirals, which are plentiful in the United States, but not widely available in low- and middle-income countries.“The administration is not spending political capital to demand that Congress act,” Asia Russell, the executive director of Health GAP, said in an interview, adding, “What we know from the global AIDS response is that decades were wasted dithering. Those wasted years translated into human lives lost. President Biden and his Covid chiefs, they have the power to change history.”The administration wants international intellectual property rules to be waived to facilitate the generic manufacture of vaccines. But the waiver request is stalled at the World Trade Organization and does not extend to treatments, drawing objections from a coalition of 170 groups led by Trade Justice Education Fund, a nonprofit that works to advance equitable trade policy.“Americans and people around the world continue to suffer not only preventable deaths and long-term health consequences, but also disruptions to economic activity and global supply chains,” the groups wrote in a letter addressed to Mr. Biden’s trade representative, Katherine Tai, adding “We need every possible tool to overcome barriers and improve equitable access to Covid-19 medical products.”

Read more →