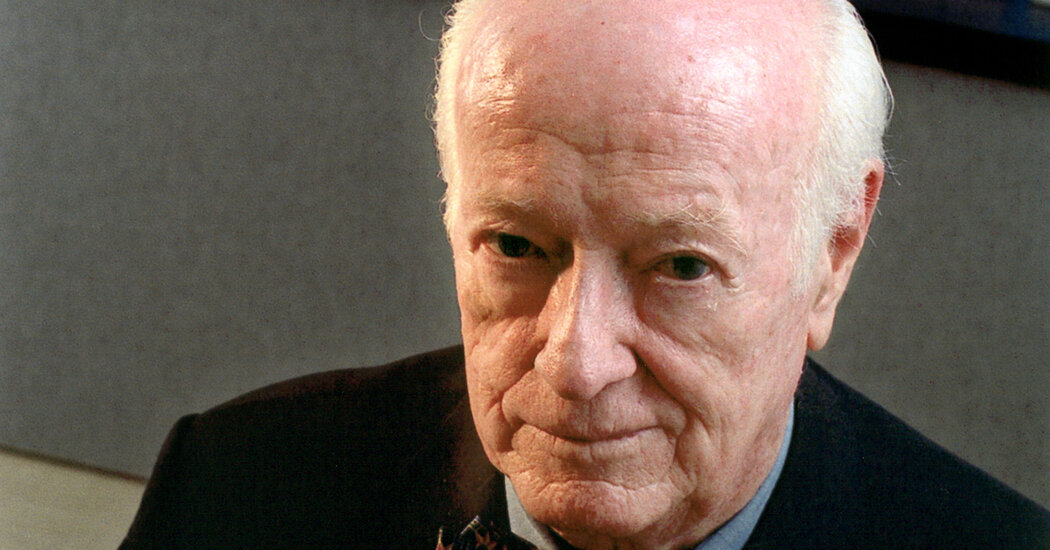

William P. Murphy Jr., an Inventor of the Modern Blood Bag, Dies at 100

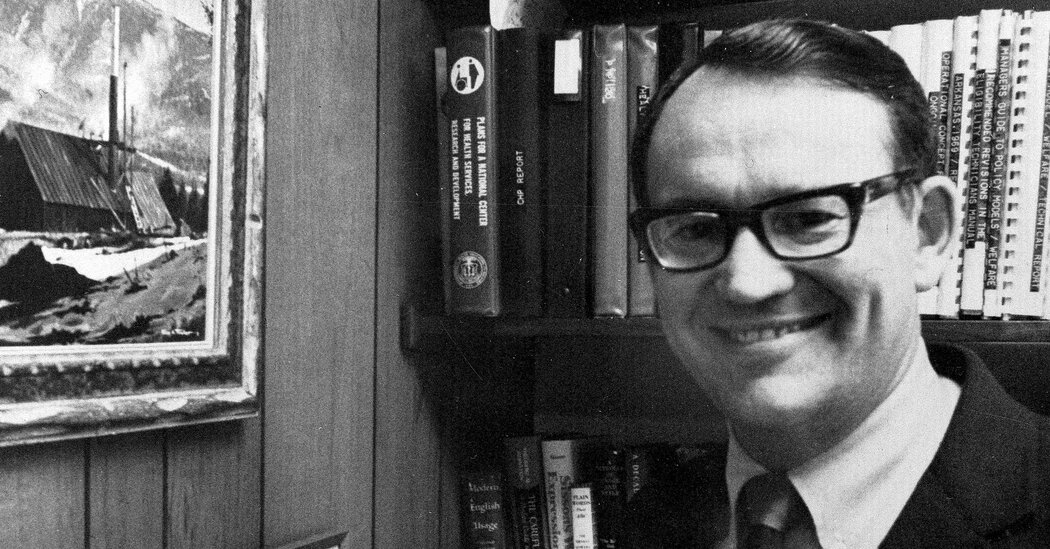

Dr. Murphy’s safe, reliable container replaced breakable glass bottles used in transfusions in the Korean War. He also helped improve pacemakers and artificial kidneys.Dr. William P. Murphy Jr., a biomedical engineer who was an inventor of the vinyl blood bag that replaced breakable bottles in the Korean War and made transfusions safe and reliable on battlefields, in hospitals and at scenes of natural disasters and accidents, died on Thursday at his home in Coral Gables, Fla. He was 100.His death was confirmed on Monday by Mike Tomás, the president and chief executive of U.S. Stem Cell, a Florida company for which Dr. Murphy had long served as chairman. He became chairman emeritus last year.Dr. Murphy, the son of a Nobel Prize-winning Boston physician, was also widely credited with early advances in the development of pacemakers to stabilize erratic heart rhythms, of artificial kidneys to cleanse the blood of impurities, and of many sterile devices, including trays, scalpel blades, syringes, catheters and other surgical and patient-care items that are used once and thrown away.But Dr. Murphy was perhaps best known for his work on the modern blood bag: the sealed, flexible, durable and inexpensive container, made of polyvinyl chloride, that did away with fragile glass bottles and changed almost everything about the storage, portability and ease of delivering and transfusing blood supplies worldwide.Developed with a colleague, Dr. Carl W. Walter, in 1949-50, the bags are light, wrinkle-resistant and tear proof. They are easy to handle, preserve red blood cells and proteins, and ensure that the blood is not exposed to the air for at least six weeks. Blood banks, hospitals and other medical storage facilities depend on their longevity. Drones drop them safely into remote areas.In 1952, Dr. Murphy joined the United States Public Health Service as a consultant and, at the behest of the Army, went to Korea during the war there to demonstrate, with teams of medics, the use of the blood bags in transfusing wounded soldiers at aid stations near the front lines.“It was the first major test of the bags under battlefield conditions, and it was an unqualified success,” Dr. Murphy said in a telephone interview from his home for this obituary in 2019. In time, he noted, the bags became a mainstay of the blood-collection and storage networks of the American Red Cross and similar organizations abroad.The vinyl blood bag developed with a colleague by Dr. Murphy, for use in transfusions. It ensures that blood is not exposed to the air for at least six weeks. Blood banks, hospitals and other medical storage facilities depend on blood’s longevity. Andreas Feininger/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Shutterstock(For years, researchers have said an ingredient in polyvinyl chlorides, diethylhexyl phthalate, or DEHP — used in making building materials, clothing and many health care products — poses a cancer risk to humans. Since 2008, Congress has banned DEHP in children’s products in the U.S.; the European Union has required labels; and alternative chemicals have replaced DEHP in blood bags.)In Korea, Dr. Murphy recalled, he saw Army medics reusing needles to transfuse patients, and medical instruments were often inadequately sterilized. Alarmed at the dangers of infection, he designed a series of relatively inexpensive medical trays equipped with drugs and sterilized surgical tools that could be discarded after a single use, greatly reducing the risks of cross-contaminating patients.In 1957, he founded the Medical Development Corporation, a Miami company that two years later became Cordis Corporation, a developer and maker of devices for diagnosing and treating heart and vascular diseases. With Dr. Murphy as chief engineer, president, chief executive and chairman, Cordis produced what he called the first synchronous cardiac pacemaker.As the use of implanted pacemakers became more common in the 1960s and ’70s, Dr. Murphy said, he saw that the devices might be improved upon to respond not only to irregular heart rhythms — usually an abnormally slow beat — but also to signs of bleeding, tissue damage, blood-clot formation or problems with the pacemaker’s electrode leads into the heart muscle.These complications led him and his team to develop a new generation of pacemakers that could be programmed externally. Out of this effort came the first “dual demand” pacemaker of the 1980s, with probes into two of the heart’s chambers for a fuller picture of the organ’s activity and creeping flaws.The advanced Cordis pacemaker contained a tiny computer that could detect heart problems and, in effect, have two-way electronic conversations with a cardiologist. The cardiologist could, in turn, devise noninvasive solutions and program the computer to carry them out.In addition, Dr. Murphy said, his team devised better ways to virtually “see” inside the vascular system. His motorized-pressure device injected, with precision, a small dose of liquid, containing iodine for color, into a selected vessel. There, the liquid showed up on an X-ray image, called an angiogram, providing a window into nooks and crannies where blockages might be lurking.To remove blockages, Dr. Murphy and a colleague, Robert Stevens, devised sterile vascular catheters, or probes, that allowed access to obstructions in vessels. (Today’s angiographic injectors have a space-age robotic look, with tiny cameras and lights in the probes and a television screen outside to guide the doctor’s way through the tunnels.)Under Dr. Murphy, Cordis also ventured into artificial kidneys, which cleanse the blood of waste products that accumulate normally in the body. Vital to sustaining life, the cleansing occurs when blood flows on one side of a membrane while a bath of chemicals flows on the other side. Impurities in the blood pass through tiny pores in the membrane into the bath, and are carried away.Dr. Willem J. Kolff, a Dutch physician, made the first artificial kidney during World War II. It was a Rube Goldberg contraption: sausage casings wrapped around a wood drum rotating in a salt solution. Dr. Murphy’s device used densely packed hollow fibers of synthetic resins as filters. Despite its inefficiencies, it was widely used in wearable or implanted artificial kidneys.Later advancements in artificial kidneys and dialysis have given thousands of patients with failing kidneys access to treatment and prolonged lives. But the devices still do not measure up to the efficient human kidney; bioengineered kidneys are still a hope of the future.Dr. Murphy retired from Cordis in 1985 to pursue other commercial medical interests. By then, he held 17 patents, had written some 30 articles for professional journals and had received the Distinguished Service Award of the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. He received the Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003 and was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2008.A wounded American soldier receiving a transfusion during the Korean War. Dr. Murphy’s vinyl blood bag was tested under battlefield conditions. Bettmann/Getty ImagesWilliam Parry Murphy Jr. was born on Nov. 11, 1923, in Boston. His father, a hematologist, shared the 1934 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for a study that showed that a diet of raw liver could ameliorate the effects of pernicious anemia. His mother, Harriett (Adams) Murphy, was the first woman to become a licensed dentist in Massachusetts.William Jr. and his older sister, Priscilla, grew up in Brookline, the Boston suburb. As a teenager Priscilla became the youngest qualified female pilot in the country but died shortly afterward in the crash of a small plane in a snowstorm near Syracuse, N.Y., on a nighttime medical-mercy flight from Boston.Fascinated as a boy with mechanics, William devised a gasoline-powered snow blower, whose design he sold to a company.After graduating from Milton Academy in Massachusetts, he studied pre-medicine at Harvard, where his father taught, and graduated in 1946. He earned his medical degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1947. While studying mechanical engineering for a year at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he developed a film projector to display enlarged X-ray images to medical audiences.Dr. Murphy interned at St. Francis Hospital in Honolulu, then practiced medicine briefly at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (now Brigham and Women’s Hospital) in Boston before taking up his career in biomedical engineering.In 1943, he married Barbara Eastham, an American linguist who had been born in China. They divorced in the early 1970s. In 1973, Dr. Murphy married Beverly Patterson. She survives him, along with three daughters from his first marriage, Wendy Sorakowski and Christine and Kathleen Murphy; two grandchildren; and one great-grandson.Dr. Murphy delivered the keynote address in 2016 at a conference held by the Academy of Regenerative Practices in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Regenerative therapy using stem cells became a particular interest in his later years. via U.S. Stem CellAfter retiring from Cordis, Dr. Murphy and a colleague, John Sterner, in 1986 bought Hyperion Inc., which designed, manufactured and marketed medical laboratory and diagnostic devices. In 2003, he joined the board of Bioheart, which developed stem cell therapies. He became chairman of Bioheart in 2010 and later chairman of U.S. Stem Cell, a successor company. In 2019, a federal court empowered the Food and Drug Administration to stop U.S. Stem Cell from injecting patients with an extract made from their own belly fat. The action came after three patients suffered severe, permanent eye damage resulting from fat extracts injected into their eyes to treat macular degeneration. The company had maintained that the extract contained stem cells with healing and regenerative powers, but medical experts disputed that claim.Dr. Murphy had by then become enthusiastic about the promise of stem cell research. In 2014, he spoke to a Miami conference about the rapidly growing and controversial field of using stem cells derived from bone marrow and umbilical cord blood to treat neurodegenerative conditions, diabetes and heart disease. “That’s a whole new world of regenerative therapy that’s going to be critical to our future,” he said.Alex Traub

Read more →