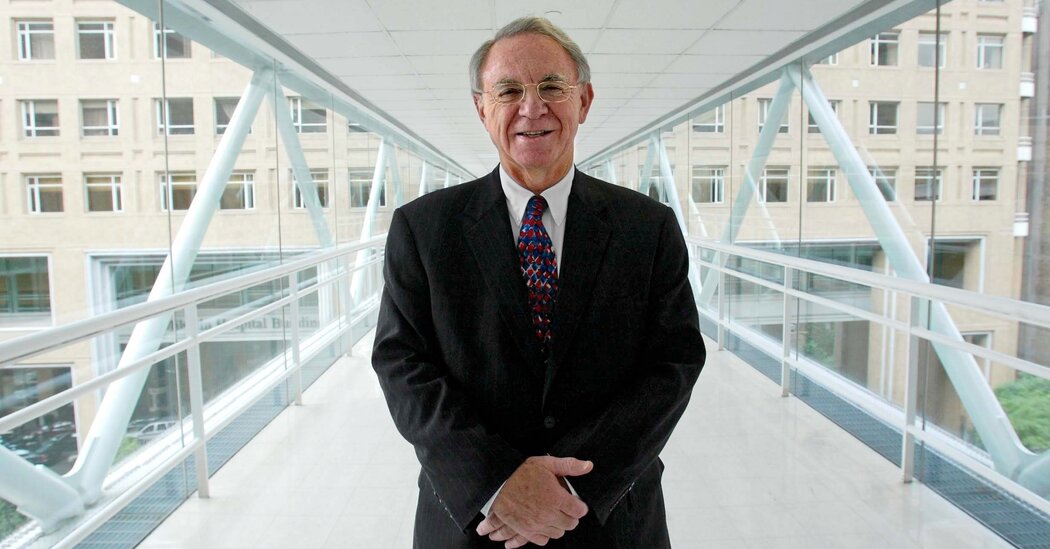

Through psychotherapy, recounted in a memoir, he learned that he had 11 personalities, or fractured parts of his identity. One of them told of childhood abuse.Robert B. Oxnam, an eminent China scholar who learned through psychotherapy that his years of erratic behavior could be explained by the torment of having multiple personalities, died on April 18 at his home in Greenport, N.Y., on the North Fork of Long Island. He was 81.His wife, Vishakha Desai, said the cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease.In the 1ate 1980s, Dr. Oxnam was president of the Asia Society, a television commentator and an accomplished sailor. But his psyche was exceedingly frail. He had myriad problems, including intermittent rages, bulimia, memory blackouts and depression, but it was for excessive drinking that he first sought treatment, from Dr. Jeffery Smith, a psychiatrist.The first personality to emerge in that therapy was Tommy, an angry boy, followed by others, like Bobby, an impish teenager, and Baby, who revealed what appeared to have been abuse when Dr. Oxnam was very young.In his 2005 book, “A Fractured Mind: My Life With Multiple Personality Disorder,” Dr. Oxnam recalled the session when Tommy first spoke to Dr. Smith. All that Dr. Oxnam could remember from the 50-minute session, he wrote, was telling the psychiatrist that he didn’t think the therapy was working for him. But Dr. Smith told him that he had been speaking to Tommy all that time.“He’s full of anger,” Dr. Smith told him. “And he’s inside you.”“You’re kidding?” Dr. Oxnam replied.His 11 personalities took up residence inside Dr. Oxnam’s brain and acted out in real life, and nearly all appeared during therapy with Dr. Smith. Wanda had a Buddhist-like presence who was once submerged in the cruel personality known as the Witch. Bobby, who loved Rollerblading with bottles balanced on his head, had an affair with a young woman, a revelation that startled Dr. Oxnam and his wife.In his 2005 memoir, Dr. Oxnam recounted therapy sessions in which his psychiatrist would find himself speaking to one or another of Dr. Oxnam’s multiple personalities. Hachette Books“It can get really noisy in there, a din,” Dr. Oxnam told The New York Times in a profile about him in 2005.Dr. Smith said in an interview, “There was a lot going on in his head, like if one personality was about to do something destructive, another was liable to say, ‘That’s not OK.’”In the book, Dr. Oxnam described how the personalities inhabited a vivid internal world — a castle with rooms, dungeons, walkways and a library behind iron-locked doors. Tommy described the castle to Dr. Smith, telling him it was “Middle Ages-style, standing on a large hill,” and was made of “gray stones and topped with long walkways and towers at the corners.”Dr. Oxnam did not reveal in the book who had abused him. But through Dr. Smith’s conversations with Baby, he wrote, Baby was “crystal clear” that the severe traumas that Robert had experienced as a boy were not inflicted by his parents.“Our vow to hide the abusers’ identity was easier said than done,” Dr. Oxnam wrote. “To be honest, when rage reigns in the Castle, it has been hard to keep quiet. But over time, I have found that withholding the abusers’ names, and refusing to stay in an angry state, actually helps the healing process.”Therapy eventually helped merge the 11 personalities into a more manageable three, he said.Dr. Oxnam with Dr. Jeffery Smith, a psychiatrist who helped identify his multiple personalities, in 2005.Hiroko Masuike/The New York TimesMultiple personality disorder — now called dissociative identity disorder — affects about one percent of the population and usually emerges after severe trauma early in life, said Dr. David Spiegel, a professor of psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine. He coined the name change, which appeared in the fifth edition of “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (2013).Dr. Spiegel said that the personalities that Dr. Oxnam experienced are better known as fragmentations of his identity.“You’re a different guy talking to me than you are at a party, but there’s a smooth continuity between the two,” he said in an interview. “In people with D.I.D., they experience themselves as different components that get filed into different identities.”The disorder was the basis for the best-selling 1973 book “Sybil,” by Flora Rheta Schreiber, about a woman who was said to have had 16 personalities. It was adapted for a 1976 made-for-television movie starring Sally Field and Joanne Woodward.Robert Bromley Oxnam was born on Dec. 14, 1942, in Los Angeles. His father, also named Robert, was president of Drew University in New Jersey and, before that, the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. His mother, Dalys (Houts) Oxnam, ran the household.He graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts in 1964 with a bachelor’s degree in history. His father urged him to consider graduate work in international studies, and Robert surmised that China would be playing a greater role on the world stage. At Yale University, he earned a master’s degree in East Asian studies in 1966 and a Ph.D. in 1969, with a dissertation on China’s 17th-century Oboi Regency.“For two years, I ferreted through court documents, biographies and local histories, all in classical Chinese, trying to find the patches of historical forest in the midst of dense linguistic trees” on the Oboi Regency, he wrote in 2014 in Perspectives on History, the American Historical Association’s newsmagazine.Dr. Oxnam at his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in 2005. The artwork was part of a collection of 18th- and 19th-century Japanese wood block prints. He was president of the Asia Society for 11 years. Hiroko Masuike/The New York TimesIn 1969, Dr. Oxnam began a six-year run as an associate professor of Chinese and Japanese history at Trinity College in Connecticut before being recruited to the Asia Society, a cultural, educational and research organization in Manhattan. He was the founder of its China Council, which issued papers and briefs about China as it began reopening to the West after President Richard M. Nixon’s visit there in 1972.As director of the society’s Washington center from 1979 to 1981, Dr. Oxnam started the organization’s first contemporary affairs department, to focus on government policy. He was named the society’s president in 1981. Over the next 11 years, he expanded its corporate, contemporary affairs and cultural programming to include 30 Asian countries and helped guide the opening of the Asia Society Hong Kong Center in 1990.Marshall Bouton, a former Asia Society executive, said Dr. Oxnam had helped transform the organization “from a gathering spot for Upper East Siders who were interested in Asia to a more professional organization that dealt with Asia’s most pressing challenges.”Mr. Bouton said that he had not been aware of the full extent of Dr. Oxnam’s alcoholism and that he had had inklings about his behavioral problems. He said that it was remarkable that Dr. Oxnam had been able to work through them.But in 1992, Dr. Oxnam told the society’s board that he was going to resign.“The Bob part of me was touched that they pressured me to reconsider,” he wrote in his book. But he left.In addition to his wife, whom he married in 1993 and who was president of the Asia Society from 2004 to 2012, his survivors include his daughter, Deborah Betsch, and his son, Geoff Oxnam, both from his marriage to Barbara Foehl, which ended in divorce in 1993, and four grandchildren.After leaving the Asia Society, Dr. Oxnam hosted and wrote a series about China for “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour” on PBS in 1993; taught a graduate seminar on U.S.-Asia relations at Beijing University from 2003 to 2004 (where his Bobby personality lectured in Chinese), and advised the Bessemer Trust, a wealth management firm.He also wrote “Ming: A Novel of Seventeenth-Century China” (1995) and turned to art, crafting found wood into sculptures inspired by Chinese philosophy and taking photographs of glacial rocks.“In Chinese tradition, the term ‘qi’ has many meanings, but for me, it means an invisible but palpable source of creative energy,” Dr. Oxnam told Hamptons Art Hub, an online publication, in 2018. He added, “I have suffered from dissociation all my life, but somehow the linkage between ‘qi’ and art has given me focus and hope.”

Read more →