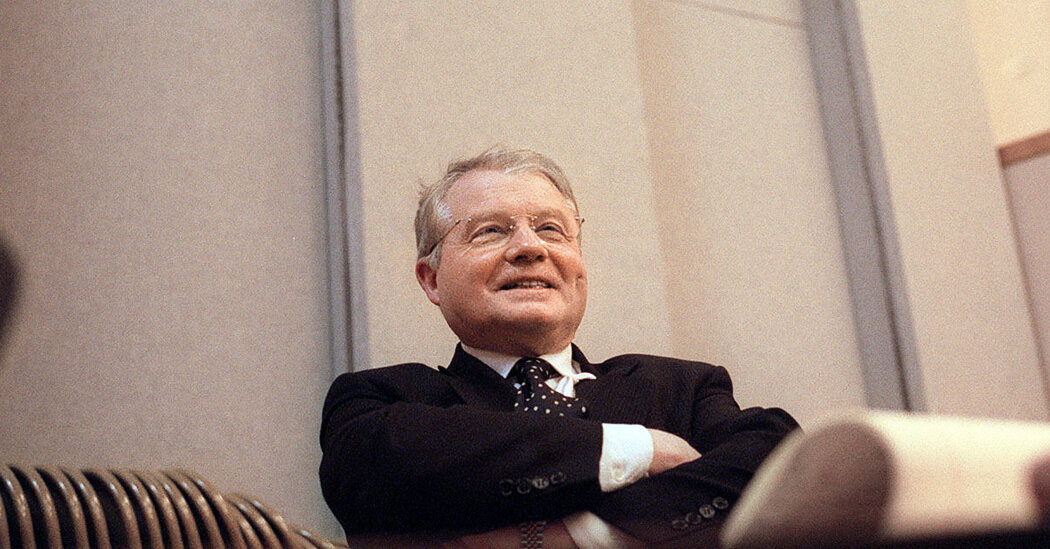

He found the virus that causes AIDS, fell into a feud over it and later turned controversial, taking an anti-vaccine stance during the Covid-19 crisis.Luc Montagnier, a French virologist who shared a Nobel Prize for discovering the virus that causes AIDS, died on Tuesday in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine. He was 89.The town hall in Neuilly confirmed that a death certificate for Dr. Montagnier had been filed there.For all the glory Dr. Montagnier earned in discovering the virus, today known as H.I.V., in later years he distanced himself from colleagues by dabbling in maverick experiments that challenged the basic tenets of science. Most recently he was an outspoken opponent of coronavirus vaccines.The discovery of H.I.V. began in Paris on Jan. 3, 1983. That was the day that Dr. Montagnier (pronounced mon-tan-YAY), who directed the Viral Oncology Unit at the Pasteur Institute, received a piece of lymph node that had been removed from a 33-year-old man with AIDS.Dr. Willy Rozenbaum, the patient’s doctor, wanted the specimen to be examined by Dr. Montagnier, an expert in retroviruses. At that point, AIDS had no known cause, no diagnostic tests and no effective treatments. Many doctors, though, suspected that the disease was triggered by a retrovirus, a kind of germ that slips into the host cell’s DNA and takes control, in a reversal of the way viruses typically work; hence the name retro.From this sample Dr. Montagnier’s team spotted the culprit, a retrovirus that had never been seen before. They named it L.A.V., for lymphadenopathy associated virus.The Pasteur scientists reported their landmark finding in the May 20, 1983, issue of the journal Science, concluding that further studies were necessary to prove L.A.V. caused AIDS.The following year, the laboratory run by the American researcher Dr. Robert Gallo, at the National Institutes of Health, published four articles in one issue of Science confirming the link between a retrovirus and AIDS (for acquired immune deficiency syndrome). Dr. Gallo called his virus H.T.L.V.-III. There was some initial confusion as to whether the Montagnier team and the Gallo team had found the same virus or two different ones.When the two samples were found to have come from the same patient, scientists questioned whether Dr. Gallo had accidentally or deliberately got the virus from the Pasteur Institute.And what had once been camaraderie between those two leading scientists exploded into a global public feud, spilling out of scientific circles into the mainstream press. Arguments over the true discoverer and patent rights stunned a public that, for the most part, had been shielded from the fierce rivalries, petty jealousies and colossal egos in the research community that can disrupt scientific progress.Dr. Montagnier sued Dr. Gallo for using his discovery for a U.S. patent. The suit was settled out of court, mediated by Jonas Salk, who had years earlier been involved in a similar battle with Albert Sabin over the polio vaccine.Dr. Montagnier in 1984 holding images of the virus found to cause AIDS. The top one was discovered by an American team led by Dr. Robert Gallo; the bottom one was detected by Dr. Montagnier’s team in Paris. The samples were later found to have come from the same patient.Associated PressBoth Dr. Montagnier and Dr. Gallo shared many prestigious awards, among them the 1986 Albert Lasker Medical Research Award, which honored Dr. Montagnier for discovering the virus and Dr. Gallo for linking it to AIDS. That same year, the AIDS virus, known by Americans as H.T.L.V.-III and the French as L.A.V., was officially given one name, H.I.V., for human immunodeficiency virus.The following year, with the dispute between the doctors still raging, President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Jacques Chirac of France stepped into the fray and signed an agreement to share patent royalties, proclaiming both scientists co-discoverers of the virus.In 2002, the two scientists appeared to have resolved their rivalry, at least temporarily, when they announced that they would work together to develop an AIDS vaccine. Then came the announcement of the 2008 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology.Dr. Gallo had long been credited with linking H.I.V. to AIDS, but the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine singled out its discoverers, awarding half the prize jointly to Dr. Montagnier and Dr. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, who had worked with him at the Pasteur Institute on the virus discovery. (The other half was awarded to Dr. Harald zur Hausen of Germany “for his discovery of human papilloma viruses causing cervical cancer.”)The Nobel committee said it had no doubt “as to who had made the fundamental discoveries” concerning H.I.V. Introducing the winners at the award ceremony in Sweden, Professor Björn Bennström, a committee member, said, “Never before had science advanced so quickly from finding the disease-causing agent to anti-viral agents.”In his acceptance speech, contrary to the views of other AIDS experts, Dr. Montagnier said he believed that H.I.V. relied on other factors to spark full-blown disease. “H.I.V. ,” he said, “is the main cause, but could also be helped by accomplices.” He was referring to other infections, perhaps from bacteria, and a weakened immune system.After his work with H.I.V., Dr. Montagnier veered into nontraditional experiments, shocking and infuriating colleagues. One experiment, published in 2009 in a journal he founded, claimed that DNA emitted electromagnetic radiation. He suggested that some bacterial DNA continue to emit signals long after an infection is cleared.The Coronavirus Pandemic: Key Things to KnowCard 1 of 3Some mask mandates ending.

Read more →