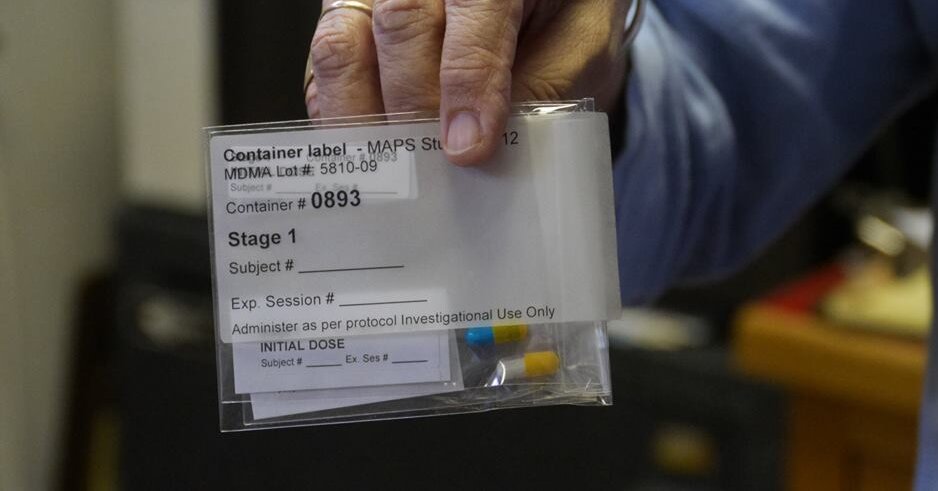

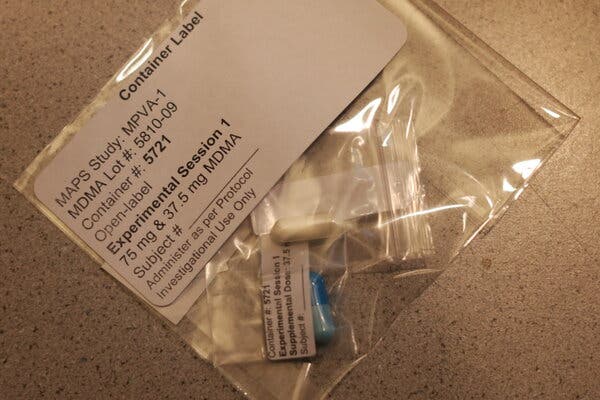

Nigel McCourry removed his shoes and settled back on the daybed in the office of Dr. Michael Mithoefer, a psychiatrist in Charleston, S.C.“I hadn’t been really anxious about this at all, but I think this morning it started to make me a little bit anxious,” Mr. McCourry said as Annie Mithoefer, a registered nurse and Dr. Mithoefer’s colleague and spouse, wrapped a blood pressure cuff around his arm. “Just kind of wondering what I’m getting into.”Mr. McCourry, a former U.S. Marine, had been crippled by post-traumatic stress disorder ever since returning from Iraq in 2004. He could not sleep, pushed away friends and family and developed a drinking problem. The numbness he felt was broken only by bouts of rage and paranoia. He was contemplating suicide when his sister heard about a novel clinical trial using the psychedelic drug MDMA, paired with therapy, to treat PTSD. Desperate, he enrolled in 2012. “I was willing to do anything,” he recalled recently.PTSD is a major public health problem worldwide and is particularly associated with war. In the United States, an estimated 13 percent of combat veterans and up to 20 to 25 percent of those deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan are diagnosed with PTSD at some point in their lives, compared with seven percent of the general population.Although PTSD became an official diagnosis in 1980, doctors still have not found a surefire cure. “Some treatments are not helpful to some veterans and soldiers at all,” said Dr. Stephen Xenakis, a psychiatrist and retired U.S. Army brigadier general. As many as half of veterans who seek help do not experience a meaningful decline in symptoms, and two-thirds retain their diagnosis after treatment.But there is growing evidence that MDMA — the illegal drug known as Ecstasy or Molly — can significantly lessen or even eliminate symptoms of PTSD when the treatment is paired with talk therapy.Last year, scientists reported in Nature Medicine the most encouraging results to date, from the first of two Phase 3 clinical trials. The 90 participants in the study had all suffered from severe PTSD for more than 14 years on average. Each received three therapy sessions with either MDMA or a placebo, spaced one month apart and overseen by a two-person therapist team. Two months after treatment, 67 percent of those who received MDMA no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis, compared with 32 percent who received the placebo. As in previous trials, MDMA caused no serious side effects.Mr. McCourry was among the 107 participants in earlier, Phase 2 trials of MDMA-assisted therapy; these were conducted between 2004 and 2017 and sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, a research group that has led such studies in the United States and abroad. Fifty-six percent of Phase 2 participants no longer met the criteria for PTSD after undergoing several therapeutic sessions with MDMA. At least one year after participation, that figure increased to 67 percent.A decade later, Mr. McCourry still counts himself among the successes. He had his first MDMA session in 2012 under the guidance of the Mithoefers, who have worked with MAPS to develop the treatment since 2000. He shared the video of that session with The New York Times. “I was suffering so badly and had so little hope, it was inconceivable to me that doing MDMA with therapists could actually turn all of this around,” he said.The second Phase 3 trial should be completed by October; FDA approval could follow in the second half of 2023.“We currently deal with PTSD as something that needs to be managed in an ongoing way, but this approach represents real hope for long-term healing,” said Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.“What makes this moment different from 20 years ago is the widespread recognition that we should leave no stone unturned in identifying new treatments for PTSD,” said Dr. John Krystal, the chair of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, who was not involved in the research. Although data from the second Phase 3 trial are needed, he says, the results so far are “very encouraging.”A need for new treatmentsDr. Michael Mithoefer and Annie Mithoefer have used MDMA doses in their therapy sessions. Though PSTD is a common diagnosis among veterans, there is no catch-all cure or treatment.Travis Dove for The New York TimesMr. McCourry, 40, lives in Portland, Ore., and comes from a military family. He joined the Marines in 2003 because he wanted to make a positive difference, he said: “When I went over to Iraq, I felt like we were there because it was for the overall good.”Understand Post-Traumatic Stress DisorderThe invasive symptoms of PTSD can affect combat veterans and civilians alike. Early intervention is critical for managing the condition.Removing the Stigma: Misconceptions about how PTSD develops and its symptoms, can prevent people from seeking treatment.Psychedelic Drugs: As studies continue to point to the therapeutic value of substances like MDMA, veterans are becoming unlikely advocates for their decriminalization.Seeking Peace: Mission Within is a Mexican retreat that uses hallucinogens to treat PTSD. Some female U.S. veterans and veteran spouses have turned to it to heal from trauma.Virtual Reality: A treatment using new technology to immerse patients in a simulation of a memory could help them overcome trauma.But he soon became disillusioned. Rather than fighting for freedom, he guarded convoys of oil. He regularly saw civilians killed. He survived an explosion that knocked him unconscious, and he suspected it may have caused lasting traumatic brain injury. He never received a diagnosis because the symptoms of traumatic brain injury — problems with thinking, sleeping and mood — overlap with those of PTSD, and the Army lacks tests that can objectively distinguish between the two conditions, Dr. Xenakis said.“I just felt like I put my life in harm’s way really for nothing,” Mr. McCourry said. “I watched friends die really for nothing.”Two months into his deployment, Mr. McCourry was caught in a firefight. Amid a hail of bullets and mortar rounds, he spotted a white truck approaching from the opposite direction. Despite signaling the truck to stop and firing a warning shot, it kept approaching.Mr. McCourry began shooting at it. Later, he learned that the people in the truck were a father and his two daughters. The father survived, but the girls did not. “The death of those girls, it haunted me,” Mr. McCourry said.In 2005, between tours of duty, Mr. McCourry sought help from a battalion medical officer for his sleep and anxiety issues. When the doctor dismissed his concerns, “I kind of lost my mind and started yelling at him,” Mr. McCourry said. Shortly after, he was honorably discharged on the basis of a personality disorder — a diagnosis that was not legitimate grounds for discharge and that Mr. McCourry vehemently disputed.At first, Mr. McCourry felt overjoyed to be home, but he soon noticed that something felt off. He was tense around friends and family. He was easily offended by any hint of perceived disrespect and found it increasingly difficult to control his anger. When he learned that nearly his entire former squad had been killed by a roadside bomb, he felt an unsettling mixture of numbness and guilt. “At that point, things spiraled,” he said.Veterans frequently struggle with the readjustment process after returning from war, but they often do so quietly. “By and large, soldiers don’t like to reveal that they have any problems, so they tend to minimize their symptoms,” said Dr. Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, the chair of psychiatry at MedStar Washington Hospital Center and a specialist in military and veterans’ issues. “Many don’t like to talk about their feelings.”Some veterans, including Mr. McCourry, also experience a phenomenon called moral injury, which frequently occurs alongside PTSD and can complicate treatment. According to Dr. Robert Koffman, a psychiatrist and retired U.S. Navy captain, moral injury develops in service members who feel responsible for perpetrating or for failing to prevent an act that violates their deeply held beliefs. The result is often intense feelings of shame and guilt.For years, vivid nightmares and paranoia prevented Mr. McCourry from sleeping properly, and he began having suicidal thoughts. Eventually, he sought help at a Veterans Affairs clinic. He received a diagnosis of severe PTSD, and the doctors recommended conventional treatments including therapy and medications.These treatments bring relief for some patients with PTSD, but they are not effective for all, said Paula Schnurr, executive director of the V.A.’s National Center for PTSD: “My take on the literature is that there is room for improvement.”Some research indicates that conventional therapy for PTSD tends to be less effective for active duty military and veterans, around 40 percent of whom drop out of treatment. “With PTSD, a pathological avoidance of triggers — which can include psychotherapy — is a core feature of the disorder,” said Dr. Joseph Pierre, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles.Mr. McCourry tried therapy, but it “didn’t help at all,” he said. The medications he was prescribed only complicated his symptoms by causing serious side effects, including disorientation and drowsiness — a common experience.For those who do not find relief through available treatments, PTSD can become chronic, debilitating and even life-threatening. On average, 17 veterans die by suicide every day, Dr. Koffman said.“I just remember wanting the suffering to end,” Mr. McCourry said. “I didn’t see any hope, and there didn’t seem like there was any path to improving. I just really wanted to die.”Finding the inner healerDr. Michael Mithoefer, left, and Annie Mithoefer have been working with MAPS since 2000. Dr. Mithoefer likened MDMA-assisted therapy to immunotherapy for cancer: “We’re stimulating the body’s own capacity for defense and healing.”Travis Dove for The New York TimesWhen Mr. McCourry first heard about MDMA-assisted therapy, he doubted it would make a difference. He met with the Mithoefers for three 90-minute preparatory sessions designed to establish trust and provide guidance on how to respond to difficult memories and feelings that might arise during treatment.The experimental sessions would last eight hours. Although Mr. McCourry knew he would be taking MDMA, under the study’s double-blind protocol he and the Mithoefers did not know what dose he would be randomly assigned. Possibilities ranged from a very low 30 milligram dose to a relatively high 125 milligram dose. Mr. McCourry’s fell in the middle, at 75 milligrams.On the day of Mr. McCourry’s appointment in 2012, as he sought to relax, Dr. Mithoefer reassured him. “We talked about not having an agenda about what should happen,” he said. “But some people find it nice to have an overall intention.”Mr. McCourry’s voice wavered. “If I had an overall intention, it’s basically just to have greater depth of understanding of mental processes and why I think the things I do,” he said. “To try to understand myself better.”Then, he swallowed the pill with a swig of water, put on eye shades and lay back. Melodic, chanting music filled the room.After about an hour, a warm sensation began to wash over Mr. McCourry in intermittent waves, and the music sounded more beautiful than before. He felt himself relax, even as he began to worry about where things were going.Soon, though, the tone of the music no longer felt inviting but ominous. Mr. McCourry considered removing the eye shades and asking the Mithoefers to stop the music. “But then I remembered that if anything uncomfortable came up, I was supposed to breathe into it versus run away from it,” he recalled.The sense of inner conflict mounted and tightened into a knot in his chest. He began remembering with embarrassment all the times he had pushed friends away when they had tried to be kind to him, and he wondered why he had behaved that way. He suddenly felt more connected to Dr. and Ms. Mithoefer and was open to exploring those questions with them.He removed the eye shades and described “this new hardness” he had developed since returning from Iraq.“What if you just let people be nice to you?” Ms. Mithoefer gently asked.“I’d have to give up control of my life in some situations,” Mr. McCourry said.“How would that look, giving up control? If someone’s trying to be nice to you?”“It could be a good experience, but I don’t even consider it before I put up these walls between me and people,” Mr. McCourry said.Trauma can result in enduring changes in genes, hormones and the brain, according to Dr. Yehuda of Mount Sinai. People with PTSD often show exaggerated levels of stress hormones, for example, and tend to have heightened activity in the amygdala, the brain region associated with processing threats and danger.That negative experiences can alter the body so significantly, however, leaves room for the possibility that equally powerful positive experiences could do the same. For many people, MDMA-assisted therapy seems to provide such a transformational reset, Dr. Yehuda said.But taking MDMA on its own, like a traditional medication, does not automatically alleviate PTSD. Rather, when paired with therapy, the drug seems to catalyze a patient’s innate capacity for psychological healing.Dr. Mithoefer likened this process to the way immunotherapy helps to fight cancer. “We’re stimulating the body’s own capacity for defense and healing,” he said.Scientists still do not fully understand how MDMA catalyzes healing. Evidence in mice indicates that the drug opens what neuroscientists refer to as a “critical period,” a window that typically occurs during childhood in which the brain is more malleable and better able to learn.“This critical-period explanation really offers a different way of thinking about it,” said Dr. Gül Dölen, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University and senior author of the findings, which were published in Nature in 2019. “MDMA is allowing you to do a cognitive reappraisal and reformulate all of the personal narrative you’ve written around the trauma.”In the Mithoefers’ office, Mr. McCourry realized that the reason he was shutting people out was because permitting them to get close would require trusting them — and trusting them would mean surrendering control. In Iraq, extreme self-reliance and distrust of others had been protective mechanisms that had helped to keep him alive. Now, those tools had become detractors.“That’s what PTSD is, really,” Dr. Mithoefer said as the three of them talked through these revelations. “You know you’re back, but there’s parts of you that haven’t taken that in yet.”Different paths to healingJohn Reissenweber saw combat in Vietnam but considered PTSD a weakness, until his wife, Stacy Turner, encouraged him to see a psychiatrist.Marissa Leshnov for The New York TimesNot everyone’s experience with MDMA-assisted therapy is as straightforward as Mr. McCourry’s.While serving in Vietnam, John Reissenweber sustained major injuries in a mortar explosion and accidentally killed a 2-year old boy. He came home a different person: always on edge and with “one of the most acid tongues there were,” he recalled recently. Like Mr. McCourry, he felt a constant need for control, and he turned to alcohol for solace.Mr. Reissenweber, now 73, never considered that PTSD might have explained his feelings and behaviors. His previous mind-set held that “to have PTSD, you’re weak.”In 2017, Mr. Reissenweber’s wife convinced him to see a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with PTSD. Despite regular appointments, his mental health did not improve. In 2019, he enrolled in the Phase 3 MDMA-assisted therapy trial.Entering the first of three sessions with MAPS-trained therapists in San Francisco, Mr. Reissenweber worried that the drug would cause him to “really come undone.” But in the weeks after the session, he felt more connected to himself and others, he said. The second session also went well.“I could take a walk outside and feel the air against my skin,” he said. “I could focus on somebody and imagine what they were thinking.”But in the third and final session, Mr. Reissenweber resolved to directly face his trauma, which took the form of a black pit. “You can’t shy away from it anymore,” he told himself, and jumped in. But rather than passing through the pit into the light, as he expected, he became stuck in the darkness and was terrified.Mr. Reissenweber could not sleep for over a week afterward, and he sometimes began shaking inexplicably. Eventually, his therapist helped him realize that the pit had represented his anger and hurt. “I’m still processing from that thing,” he said.Despite the difficulty, Mr. Reissenweber said his experience with MDMA-assisted therapy significantly changed his life for the better. He now finds traditional therapy to be productive and has been able to deeply connect with others, including his spouse, who he calls his guardian angel.“It made me realize there was a reason for my hurt and my fears, and that I could change the outcome,” he said.Clarity and compassionMr. McCourry with his dog, Kiko, at home. He recently became a father and, after a 10-year struggle, had his discharge order changed to combat-related PTSD.Amanda Lucier for The New York TimesMr. McCourry emerged from his first session of MDMA-assisted therapy with what he described as an aerial map of his mind. “It’s just been so tangled up, I didn’t even know where to start,” he told the Mithoefers.He slept soundly that night, and his sleep problems never returned.In one of his later sessions with MDMA, he revisited the memory of the two girls he had accidentally killed and saw that he had been harboring a tremendous amount of self-loathing for the person he had become in Iraq. He was able to replace the contempt he felt toward “Nigel the Marine,” as he put it, with compassion.Mr. McCourry recently became a father and — after a nearly 10-year long bureaucratic struggle — successfully convinced the Navy to correct his reason for discharge to combat-related PTSD, instead of passive-aggressive personality disorder.He still sometimes becomes overwhelmed in stressful situations and “just starts to mentally shut down,” he said. But he is now able to recognize when this is happening and to better manage his feelings.“It’s really important for me that these experiences I’m sharing are used to show people that there is hope,” Mr. McCourry said. “I’ll keep doing what I can to support this therapy until it’s legalized.”

Read more →