Supporters of Aid in Dying Sue N.J. Over Residency Requirement

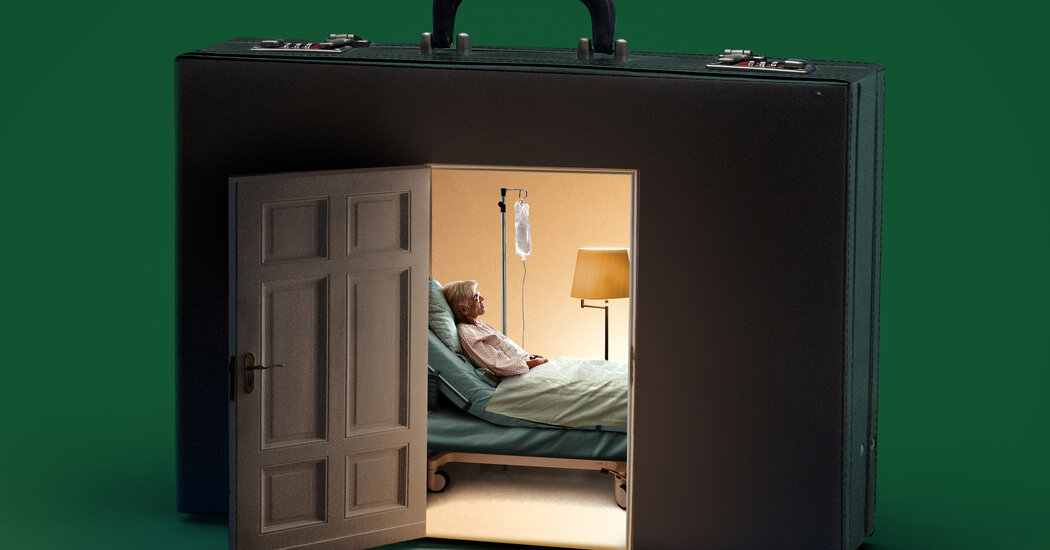

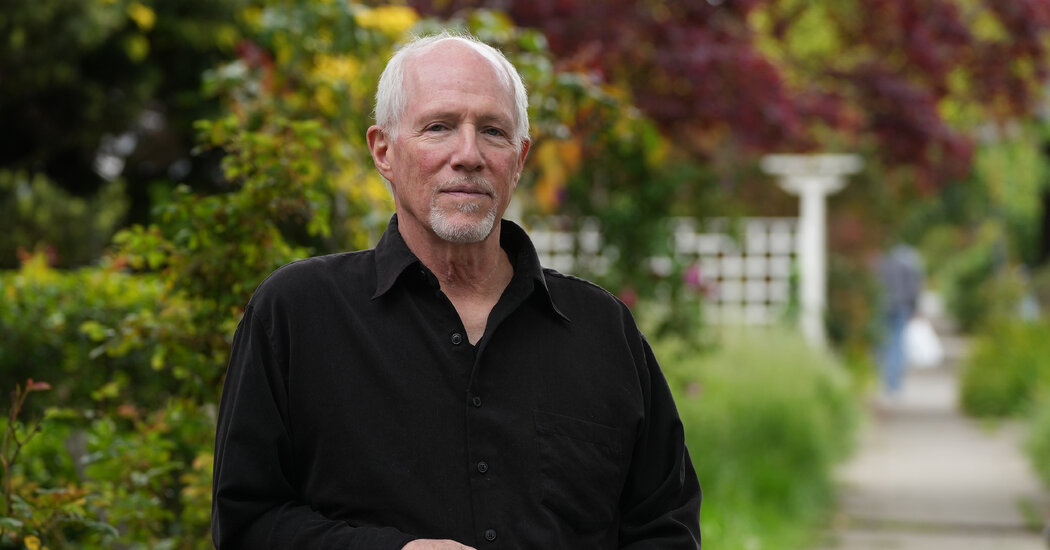

If the state were to change its course, aid in dying would become more accessible to millions of Americans.Judy Govatos has heard that magical phrase “you’re in remission” twice, in 2015 and again in 2019. She had beaten back Stage 4 lymphoma with such aggressive chemotherapy and other treatments that at one point she grew too weak to stand, and relied on a wheelchair. She endured several hospitalizations, suffered infections and lost nearly 20 pounds. But she prevailed.Ms. Govatos, 79, a retired executive at nonprofit organizations who lives in Wilmington, Del., has been grateful for the extra years. “I feel incredibly fortunate,” she said. She has been able to take and teach lifelong learning courses, to work in her garden, to visit London and Cape Cod with friends. She spends time with her two grandchildren, “an elixir.”But she knows that the cancer may well return, and she doesn’t want to endure the pain and disability of further attempts to vanquish it.“I’m not looking to be treated to death. I want quality of life,” she told her oncologist. “If that means less time alive, that’s OK.” When her months dwindle, she wants medical aid in dying. After a series of requests and consultations, a doctor would prescribe a lethal dose of a medication that she would take on her own.Aid in dying remains illegal in Delaware, despite repeated legislative attempts to pass a bill permitting it. Since 2019, however, it has been legal in neighboring New Jersey, a half-hour drive from Ms. Govatos’s home.But New Jersey restricts aid in dying to terminally ill residents of its own state. Ms. Govatos was more than willing, therefore, to become one of four plaintiffs — two patients, two doctors — taking New Jersey officials to federal court.The lawsuit, filed last month, argues that New Jersey’s residency requirement violates the Constitution’s privileges and immunities clause and its equal protection clause.“The statute prohibits New Jersey physicians from providing equal care to their non-New Jersey resident patients,” said David Bassett, a lawyer with the New York firm Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr, which brought the suit with the advocacy group Compassion & Choices.“There’s no justification that anyone has articulated” for such discrimination, he added. The suit also contends that forbidding New Jersey doctors to offer aid-in-dying care to out-of-state patients restricts interstate commerce, the province of Congress.The New Jersey Attorney General’s office declined to comment.“I’d like not to die in horrible pain and horrible fear, and I’ve experienced both,” Ms. Govatos said. Even if she enrolls in hospice, many of the pain medications used cause her to pass out, hallucinate and vomit.To be able to legally end her life when she decides to “is a question of mercy and kindness,” she said.It’s the third time that Compassion & Choices has pursued this route in its efforts to broaden access to aid in dying. It filed similar suits in Oregon in 2021 and in Vermont last year. Both states agreed to settle, and their legislatures passed revised statutes repealing residency requirements, Oregon in July and Vermont in May.The plaintiffs hope New Jersey, another blue state, will follow suit. “We hope we never have to go before a judge. Our preference is to negotiate an equitable resolution,” Mr. Bassett said. “That’s what’s important for our patient plaintiffs. They don’t have time for full-fledged litigation.”“It’s not the traditional process of trying to convince a state legislature that this is a good idea,” said Thaddeus Pope, a law professor at Mitchell-Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, Minn., who tracks end-of-life laws and court cases.Dropping residency requirements in New Jersey could have a far greater impact than it will in Oregon or Vermont. The sheer population density along New Jersey’s borders — there are almost 20 million residents in the New York metropolitan area alone — means medical aid in dying would suddenly become available to vastly more people, and much more quickly than it would through legislation.With a major airport and direct flights, “it’s easier to get to Newark than Burlington, Vermont,” Mr. Pope pointed out.Many states where aid in dying is legal have relaxed their statutes because of findings like those in a 2017 study, in which about a third of California patients who asked a doctor about aid in dying either died before they could complete the process or became too ill to continue it.But New Jersey still uses the stricter series of steps that Oregon first codified in 1994. That means two verbal requests to a doctor at least 15 days apart, a written request with two witnesses, and a consultation with a second physician; both must confirm that the patient is eligible. There’s a 48-hour wait after the written request before a prescription can be written.Even without having to establish residency, “it won’t be a walk in the park,” Mr. Pope said. “You can’t just pop over to New Jersey, pick up the drugs and go back.”Finding a doctor willing to prescribe can take time, as does using one of the state’s few compounding pharmacies, which combine the necessary drugs and fill the prescription.Although no official would check to see whether patients travel home with the medication, both Mr. Bassett and Mr. Pope advise that the lethal dose ought to be taken in New Jersey, to avoid the possibility of family members facing prosecution in their home states for assisting in a suicide.Still, preventing dying patients from having to sign leases and obtain government IDs in order to become residents will streamline the process. “Not everyone has the will, the financial means, the physical means” to establish residency, said Dr. Paul Bryman, one of the doctor plaintiffs and hospice medical director in southern New Jersey. “These are often very disabled people.”Bills recently introduced in Minnesota and New York don’t include residency requirements at all, Mr. Pope noted, since they seem likely to be challenged in court.“I think the writing’s on the wall,” he said. “I think all the residency requirements will go, in all the states” where aid in dying is legal. There are 10, plus the District of Columbia (though the legality in Montana depends on a court decision, not legislation).Despite the often heated wrangling over aid-in-dying laws, very few patients actually turn to lethal drugs in the end, state records show. Last year, Oregon reported that 431 people received prescriptions and 278 died by using them, just .6 percent of the state’s deaths in 2022.In New Jersey, only 91 patients used aid in dying last year. Roughly a third of those who receive prescriptions never use them, perhaps sufficiently reassured by the prospect of a swift exit.Fears of “death tourism,” with an onrush of out-of state patients, have not materialized, said John Burzichelli, a former state assemblyman who helped steer New Jersey’s statute through the legislature and now favors allowing eligible nonresidents to participate. “I don’t see lines of people at the tollbooths coming to take advantage of this law,” he said.If her cancer returns and New Jersey has balked at allowing out-of-staters to legally end their lives there, Ms. Govatos contemplates traveling to Vermont. She envisions a goodbye party for a few friends and family members, with poetry reading, music and “very good wine and lovely food.”But driving over the Delaware Memorial Bridge would be so much simpler. “It would be an incredible gift if I could go to New Jersey,” she said.

Read more →