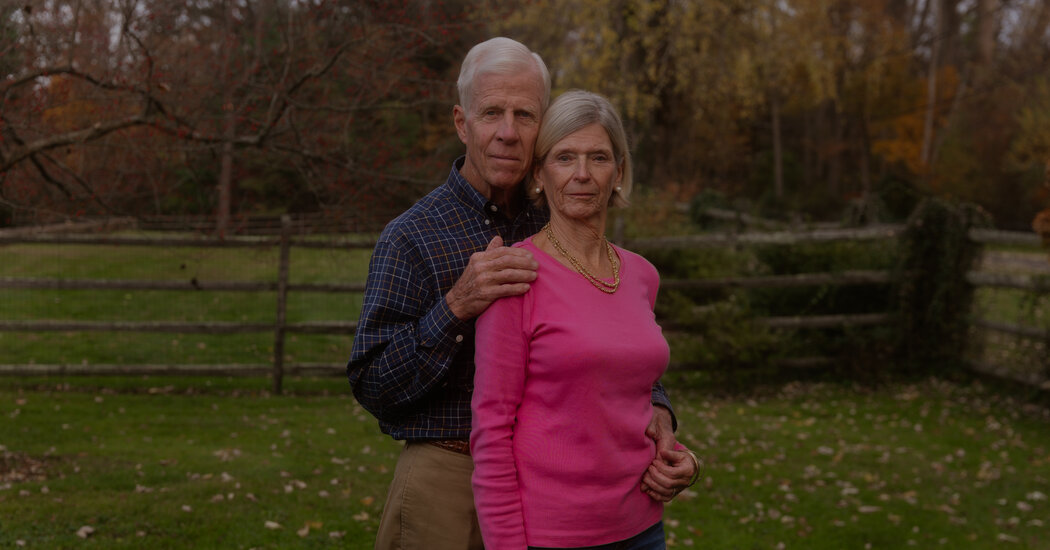

Some seniors prefer age-restricted communities, while others want intergenerational living. There is little research to show which option is healthier.Kathy Fitts loved her roomy house in suburban Atlanta. But after her children moved out, and the pandemic exacerbated the isolation she often felt as a divorced woman, she left for Latitude Margaritaville, a Jimmy Buffett-themed housing development in Daytona Beach, Fla., for those “55 and better.”Visiting a friend who had relocated there, “I thought, wow, these people are having a good time,” Ms. Fitts, 68, said. She bought a two-bedroom villa and settled in almost two years ago.“I’m loving it,” she said. “There are so many things to do.” Traveling around in her golf cart, she plays bocce and bunco, takes birding walks and goes to tribute band concerts. You probably couldn’t pry her out with a crowbar.Do older people benefit from living exclusively with other older people? That’s the standard model for senior housing of many configurations: independent and assisted living, continuing care retirement communities (also called life plan communities), 55-plus developments, subsidized affordable complexes.But the prospect of life in an age-restricted development makes Robyn Ringler shudder. She and her husband, both retired in upstate New York, downsized from a big house on 30 rural acres to a rented one near an elementary school in suburban Albany.“I love my friends who are the same age as me, but I adore meeting and knowing people of all ages,” said Ms. Ringler, who is 66. She meets people while biking through her neighborhood or walking her goldendoodle; she knows trick-or-treaters by name.“It keeps me more engaged with the world,” she said. “It makes me feel part of a real community, a larger family.” As for the couple’s actual family, their adult daughter, who is about to start a new job, has moved in with them temporarily — something 55-plus communities typically ban.Though surveys repeatedly show that most older people prefer to remain in their own homes as they age, about 800,000 were in assisted living last year, according to LeadingAge, which represents nonprofit aging services providers. An additional 745,000 lived in continuing care communities and three million in federally supported affordable senior housing.The National Investment Center for Seniors Housing and Care estimates that 540 active adult communities with 82,000 units offer market-rate rental properties for seniors. In other 55-plus developments, residents purchase houses and condos.Age-restricted housing often requires a middle- or upper-middle-class income. Homes at the Margaritaville community in Daytona Beach, for example, start at about $300,000.At Riderwood, a continuing care community in Silver Spring, Md., that Lynn Cave moved into in 2021, the entrance fee for her one bedroom-plus-den apartment was $270,000 (90 percent is refundable after a resident moves out or dies). Her $3,300 monthly fee includes utilities; cable, phone and internet; use of the pool and fitness center; and 30 meals a month.Often, as in Ms. Cave’s case, the sale of a house covers the costs. Low-income seniors have far fewer options.The Jimmy Buffett-themed housing development, Latitude Margaritaville, has drawn many “55 and better” residents.Dustin Miller for The New York Times“There are so many things to do,” Ms. Fitts said of her new home.Dustin Miller for The New York TimesYet research on whether age-segregated housing leads to improved health or quality of life is scant and dated; it’s not a subject that lends itself to controlled studies. “It’s still an open question,” said Jennifer Molinsky, director of the Housing an Aging Society program at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies.The motives for relocating vary, of course. Ms. Cave, 67, moved to Riderwood because “I was the daughter who had to take care of parents from afar, and I swore I’d never do that to my kids,” she said.At first, Ms. Cave recalled, “I looked around and saw the walkers and the scooters and thought, ‘My God, what have I done?’” Now, though, she appreciates the community college courses offered on campus, the square dancing and the pickleball, the shared meals. “The people are so interesting,” she added.Such graduated communities allow residents to transfer to assisted living, nursing care or memory care units as their health declines. It’s a benefit that Carol Holmes Alpern, 81, learned to value after she and her husband, Bowen Alpern, moved into Foulkeways, a nonprofit Quaker-affiliated continuing care community in Gwynedd, Pa.A healthy 68-year-old when he arrived in 2021, Mr. Alpern was diagnosed with a brain tumor the following year. When his wife could no longer care for him by herself, he entered hospice care in the Foulkeways nursing center, a short walk from the couple’s apartment. Having the option of 24-hour aides and unlimited visiting hours “probably saved my life,” Ms. Alpern said.Her husband died last month, and now, “I can’t imagine leaving,” she said. Other residents “not only supported both of us, they cherished us.”No such safety net awaits residents of so-called active adult communities, age-restricted developments that can offer rentals or homeownership. But “I see why they’re popular,” Dr. Molinsky said.“They’re lower maintenance than a single-family home,” she said. “They’re more likely to have accessibility features. If the design is thoughtful, with proximity, you have opportunities to socialize. And municipalities are more apt to approve projects that don’t increase school budgets.But Toni Keyes, 65, moved into an apartment in a small 62-plus community in Clearlake, Calif., last year after the single-family homes she had been renting were sold, twice. A retired library worker living on Social Security disability, she found the apartment rent affordable with her federal Section 8 voucher, but the environment unwelcoming and unpleasant.“It’s like a ghost town, always quiet,” said Ms. Keyes, who also remains very conscious of being the only Black tenant. “It feels like a nursing home.“Being surrounded by all seniors is very limiting,” she added. “There should be a mix of age groups.”That’s difficult to find, but “I definitely see growing interest in creating models of intergenerational housing,” Dr. Molinsky said. Some developers and operators have introduced mixed-age programs within senior housing or have built complexes that place senior buildings next to all-age apartments.In Long Island City, N.Y., for instance, the Gotham Organization last year opened an 11-story senior independent living building, part of 1,132 units of housing at rents that range from low to upper income.Though older residents, whose units provide grab bars and other safety features, and younger tenants don’t live side by side, they share a rooftop farm and other amenities and programs that encourage interaction. “They’re in the same ecosystem,” said Bryan Kelly, president of development.Another Gotham development on the Lower East Side of Manhattan will incorporate a Jewish cultural center at the base of the senior building and a large community center in the adjacent all-ages building. “The days of the suburban model, the circular drive-up, are over,” Mr. Kelly said. He expects “more integrated, walkable, active, mixed use” senior housing.Creating intergenerational housing will require federal and local policy changes, said Robyn Stone, senior vice president for research at LeadingAge. “We don’t have the regulatory environment that allows some of these things to happen, or the incentives to encourage and support them,” she said.A few experiments in intergenerational living serve as proof of concept. In Oregon, Bridge Meadows has developed three communities, with more to come, for older adults and for families adopting or fostering children from the foster care system.Treehouse Communities has built a similar combination in Easthampton, Mass. Olmsted Village in Mattapan, a Boston neighborhood, will offer homeownership to middle-income families along with apartments to fostering and adopting families — and to seniors who will mentor them. Some Cohousing communities are seniors-only, but others draw residents of all ages.For now, though, when older people want or need to leave their homes, they usually acquire neighbors who are also, exclusively, older.“I don’t know, if you asked people, if that’s what they want,” said Susan Popkin, a fellow and housing researcher at the Urban Institute. “But we haven’t asked.”

Read more →