Telemedicine for Seniors Gets a Last-Minute Reprieve

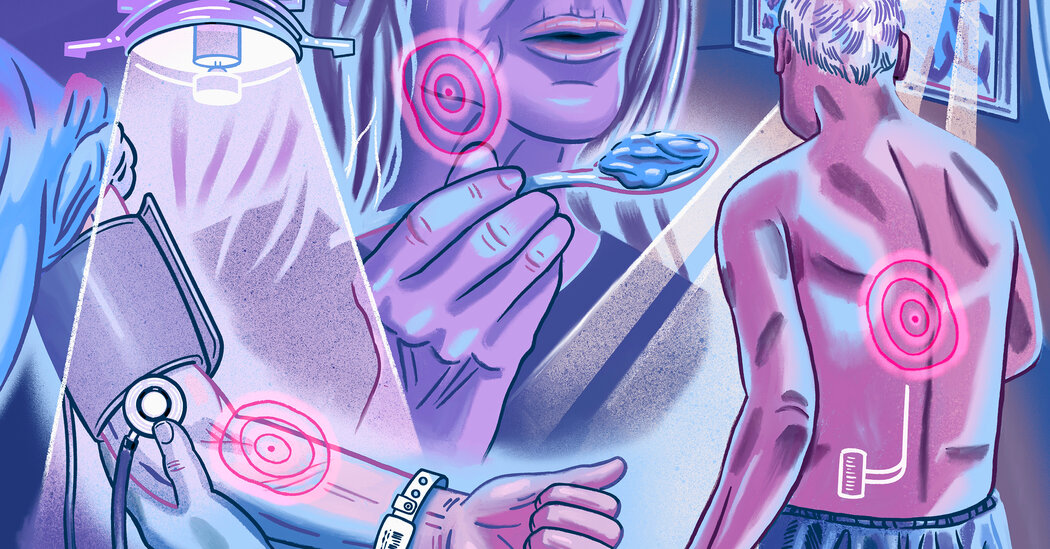

Some older Americans have come to depend on virtual consultations with doctors, covered by Medicare. To keep that option in the future, Congress will have to act quickly. Since his cancer diagnosis last year, Kent Manuel has regularly seen an oncologist near his home in Indianapolis. It’s been a tough time: After spinal surgery for paralysis caused by his cancer, he is regaining the use of his legs with physical therapy but still uses a wheelchair.Now, Mr. Manuel said, “I’m dealing with pain.” His oncologist recommended palliative care, a medical specialty that helps people with serious illnesses cope with discomfort and distress and maintain quality of life.So in November, Mr. Manuel, 72, a semiretired accountant, started seeing Dr. Julia Frydman, a palliative care doctor. “We talk through what works and what doesn’t,” he said. “She listens to what I have to say. She’s very flexible.”The first two medications she prescribed to reduce pain had troublesome side effects. On the third try, though, “I think we’ve landed on something that’s working,” he said. His pain hasn’t fully abated, but it has diminished.Dr. Frydman, the senior medical director at a cancer care technology company called Thyme Care, works hundreds of miles away in a Manhattan office. She and Mr. Manuel used a video telemedicine link — an option that barely existed in traditional Medicare before the Covid pandemic, thanks to restrictive federal policies.Medicare expanded its telemedicine coverage substantially in 2020, and the expansion has regularly been renewed. That could all have ended on Dec. 31.We are having trouble retrieving the article content.Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.Thank you for your patience while we verify access.Already a subscriber? Log in.Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Read more →