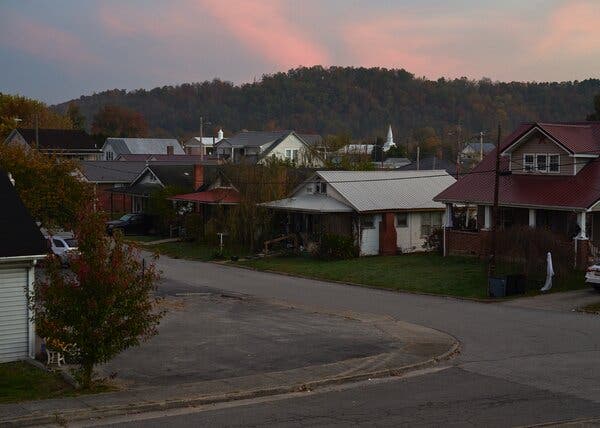

Walk down two flights of stairs, accessed through the back entrance of the James Hunt Funeral Home in Asbury Park, N.J., and you reach a white-walled, linoleum-floored, fluorescently-lit room, a liminal space that provides the beginning of an answer to one of the oldest and most confounding questions of the human experience: What happens to us when we die?On a recent Tuesday evening, Shawn’te Harvell walked down the steps and into the room, where two bodies, covered in white cloth, lay on gurneys. Mr. Harvell was wearing crisp gray scrubs and two-tone leather shoes. This was a departure from his usual attire, noted Vivian Velazquez, the funeral home manager. “Usually he’s here in his three-piece suit, his $500 shoes, and he doesn’t even wear that,” she said, pointing to the thin plastic apron that Mr. Harvell had tied around his waist.Mr. Harvell smiled and shook his head. His job, by most metrics, is a messy one. He was in the room to embalm the bodies — to drain the blood vessels and cavities filled with fluid, refill them with preservatives, scrub the skin, suture any cuts, clean the teeth, sew the mouths closed. He was there to massage the illusion of life back into cold, dead cells. But Mr. Harvell has been studying embalming and practicing as an embalmer for nearly a quarter of a century, beginning when he was 16. So, no apron necessary.Shawn’te Harvell is a professor of mortuary science, the manager of the James Hunt Funeral Home and a trade embalmer in New Jersey.James Estrin/The New York TimesNow in his 40s, Mr. Harvell is a professor of mortuary science at a local college, the manager of his own funeral home in Elizabeth and a trade embalmer who does nearly 50 embalmings a week; he is familiar with the often fraught area between life and death. “My ultimate goal is to give them their loved one back,” he said of the people who would view the bodies at the upcoming funerals. “I’ve had families come up to me and tell me, ‘Wow, they look so nice I couldn’t even cry.’”But the world he belongs to, the world of embalming, is increasingly losing its sway over the American way of death.Data gathered by the National Funeral Directors Association shows that nearly 60 percent of Americans were cremated in 2021, an increase from around 25 percent in 1999. More than 60 percent of people surveyed were interested in having so-called green burials, which are cheaper than traditional funerals and limit the chemicals allowed into the body for preservation. Embalmers are becoming more difficult to find; most funeral homes rely on contractors like Mr. Harvell, who may be the sole embalmers for a dozen funeral-home clients.According to people in the industry, things have been trending away from embalming for decades. “Absolutely there’s a shift going on,” said Tim Collison, the chief operating officer of The Dodge Company, the largest embalming fluid manufacturer in the country. “There’s less demand — it’s not an expanding market.” Dr. Basil Eldadah, a physician with the National Institute on Aging, said, “We’re just in this place in our society where we’re questioning the way that things have always been done.”The end beginsAll human life is funneled through the narrow channel of death. The heart stops beating, neurons stop firing, muscles tense and begin to decay, cells decompose. From then on, the possibilities only expand.You can be embalmed with formaldehyde and placed in a coffin underground; cremated in a furnace; left out in the open air; liquefied in an alkaline solution; composted under a pile of mulch; frozen in a cryogenic container; mummified; planted at the roots of a sapling. Ed Bixby, who owns 13 cemeteries around the country, said a new technique of treating dead bodies comes into fashion every year or so. Would you rather not have your ashes compressed into a diamond? Then how about freeze-drying your body and vibrating it into dust?But, Mr. Bixby added, nothing has managed to outlive cremation and embalming and burial: “Everyone just goes with the norm because that’s what’s normal.”The James Hunt Funeral Home. “My ultimate goal is to give them their loved one back,” Mr. Harvell said of mourners.James Estrin/The New York TimesMethods of body preservation go back thousands of years, to the 7,000-year-old Chinchorro mummies found in the Atacama Desert in Chile. But the most famous examples are from ancient Egypt. Deceased pharoahs and members of wealthy families underwent a monthslong mummification process that involved removing their internal organs, drying their bodies out with natron salt and rubbing oil on their skin. Behind this ritual was the idea that a part of the person’s spirit lived in the body, and that it would be lost if the body was destroyed. The process was so effective that some mummies could be dug up by archaeologists, with the skin and facial structure more or less intact, 4,000 years later.Egyptian mummification, aimed at eternity, bears little resemblance to modern American embalming, which began during the Civil War, when bodies of soldiers had to be transported on hot, unventilated trains. The objective was temporary preservation, maintaining an illusion of life just long enough for people to say goodbye. Abraham Lincoln was embalmed and paraded around the country after his assassination in 1865, the embalming treatment continually applied as his death tour went on for weeks. As embalming gained popularity and legitimacy through the 20th century, the viewing of the body often served as the centerpiece of the funeral ritual.Methods and intent vary widely, shaped by cultural and circumstantial forces. But the belief underlying these ancient and modern practices seems to be somewhat universal — that the body contains some part of the person, some essence, some meaning.“It’s quite profound,” said Dr. Raya Kheirbek, the chief of the Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. “Even after death claims the body, we’re going to beautify it in some way — like, death cannot win.”‘You’ve got to die from something’Downstairs in the James Hunt Funeral Home, Mr. Harvell moved swiftly and deftly. The two bodies he was embalming were opposites: one small and bony, almost to the point of emaciation, the other large, the legs and feet swelling with edemas.Every embalmer has a signature, Mr. Harvell said, as he pulled 16-ounce bottles of embalming fluid from the shelves of a tall wooden closet in the corner of the room. A bottle of orange fluid from The Dodge Company, 20 percent formaldehyde gas, dissolved in water — “20-index” — and mixed with plasticizers to keep the body from stiffening. A bottle of blue, 36-index fluid from Bondol Labs; designed for “frozen, refrigerated and cold bodies,” it contained salts with large ions to draw fluid out of the skin and keep it in the capillaries. A bottle of violet-red 18-index fluid from the Embalmers Supply Company for color and firmness. “We all have a certain thing we do,” Mr. Harvell said, dumping the liquid into a plastic tub atop a pressurized machine to create a frothy, turquoise mixture.Embalming fluids.James Estrin/The New York TimesShawn’te Harvell, left, does nearly 50 embalmings a week. He has been studying or doing embalming for more than 25 years.James Estrin/The New York TimesFormaldehyde sits at the heart of the embalming process. The gas fixes onto tissue proteins, stiffening them and inhibiting decomposition for roughly 24 hours. It is a vast improvement over the earliest embalming techniques, which sometimes entailed soaking a body in alcohol. But exposure to formaldehyde has been linked to cancer, and the door to Mr. Harvell’s room was plastered with biological hazard signs. He seemed unconcerned. “You’ve got to die from something,” he said with a shrug.The trick is to distribute the fluid throughout the body, starting with a two-inch cut above the clavicle, through which arterial fluid is pumped into the carotid artery. The stomach is emptied, the contents replaced with high-index cavity fluid that dries and firms up the insides. The skin is scrubbed and washed, the cut sutured shut, the lips sewed together, makeup applied.But to say that this is the extent of embalming, to embalmers, is like saying to a painter that painting consists only of long and short brushstrokes, or saying to a writer that writing consists only of subjects and clauses. Mr. Harvell, looking up from his work, said, “I can teach the fundamentals of embalming, but to do it proficiently, to do it with that …” — he twisted his fist forward and back for emphasis — “you got to have it in you.”There are products that dry out tissue, preventing liquid from leaking out of the pores of bloated bodies; powders to seal particularly large cuts; fluids with hues that counter the yellowing of jaundice. Dodge’s best-selling chemical is Introfiant, a high-index arterial fluid that some embalmers call Purple Jesus. “That’s because if they had to say a prayer to get the embalming done, they would grab the Introfiant,” Mr. Collison said.But merely knowing the embalming basics and having the right tool kit is insufficient, said Krystal Osborne, an embalmer based in Las Vegas: “You’re given a picture, and you’re creating that person all over again.”The casket showroom at Mr. Harvell’s funeral home. Nearly 60 percent of Americans were cremated in 2021, an increase from around 25 percent in 1999. James Estrin/The New York TimesTo embalm or not to embalmA few years ago, Dr. Kheirbek was invited to the funeral of one of her patients. It had been a week since the man had died, and Dr. Kheirbek and her team stood over the embalmed body, which lay in an open casket in the funeral home.“For a moment, we thought we’d gone to the wrong visitation,” she later wrote in a journal article. “He looked better than he ever looked during the months we cared for him. His face was pink and smooth, his hair nicely groomed, and he sported a quiet smile. The Mr. Thompson we knew was a skeleton, with tight-drawn skin, long curly hair, and a shaggy beard.”This incongruity triggered something in Dr. Kheirbek. It almost felt wrong to her, she wrote, like a willful blinding. The man was dead; why did he look like he was alive?Jessica Mitford, in her 1963 book about the funeral industry, “The American Way of Death,” noted pointedly that many funeral homes took financial advantage of their customers by preying on “the disorientation caused by bereavement” and “the need to make an on-the-spot decision.” Today, the average embalming and funeral costs nearly $10,000. Burial plots and headstones cost even more. Much of this can ease the grieving process for people, Dr. Kheirbek said. But, she added, why pump the body with chemicals and restore it to reflect some past self?In Japan, Nepal, Korea and Taiwan, nearly every body is cremated, while in most other countries, bodies are buried without being preserved artificially. Religion often plays an important role in these practices, but it can’t explain everything. The collection of trendy alternatives to embalming, burial and cremation that spring up each year often claim to be not just another option of body disposition, but a challenge to the social norms that shape how we treat and view the dead body.Among the more prominent movements is that of the green burial. Some experts estimate that cremation in the United States releases half a million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year. Others note that burials introduce four million tons of embalming fluid into the ground, and 1.6 million tons of concrete.Ed Bixby owns 13 cemeteries and promotes natural burials using biodegradable coffins.James Estrin/The New York TimesMr. Bixby is the president of the Green Burial Council, a nonprofit that promotes natural burials, which consist of placing bodies in biodegradable coffins to reduce environmentally harmful waste. Dr. Eldadah, who is working to open a green-burial cemetery in Maryland, said that natural burials offered a potent philosophical alternative to what the philosopher Thomas Nagel called “the expectation of nothingness.”“It’s not this fatalistic understanding of death as unavoidable, but it is a part of the cycle of life,” Dr. Eldadah said. “We need death in order to live happy lives, making space in order for more life to emerge.”Dr. Kheirbek, who is friends with Dr. Eldadah, added: “And that’s the utmost love, I think. To just be able to let go.”Mr. Collison’s company has developed a formaldehyde-free embalming fluid as a way to cater to the growing green burial demand, but he noted that of the nearly 50 billion pounds of formaldehyde that are produced every year, only a few million pounds end up in embalmed bodies. “When you look at the funeral service from a worldview, it doesn’t make a lot of sense,” he said of embalming. “But I think there’s a basic human need to say goodbye.”A chapel built by Mr. Bixby; it is a replica of his family chapel, which was constructed in 1910.James Estrin/The New York TimesLife and everything afterAs Mr. Harvell embalmed the two bodies, massaging stiffness out of the joints and pushing the arterial fluid through the blood vessels, Ms. Velazquez and Xenia Ware, the owner of the funeral home, stood nearby and chatted about clients. One family, they said, had insisted on holding a funeral service in northern New Jersey, then leading a procession an hour south on the Garden State Parkway to the burial.Mr. Harvell seemed to register what was being said, while fragmenting his attention toward his work and the Airpod Pro that was squeezed into his right ear, through which he was carrying on a conversation with a friend. “That’s fine,” he whispered, and it was hard to tell whether he was speaking to the living or the dead.The air in the basement room was slowly filling with formaldehyde, which carried with it a cloying odor. The fluid had been emptied out of the machine, the blood drained into buckets hanging off the end of the gurneys; Mr. Harvell washed the bodies again, massaging them as he went. He put dots of oil gel on their faces to moisturize the skin, then recalled aloud how a man had once called him to arrange his own funeral.“He said, ‘I’ll be gone in about two weeks,’” Mr. Harvell said. “And I said, ‘Nah, you’ll be OK.’” The man seemed strong to Mr. Harvell; he knew him from the community, and it seemed preposterous that he could die on such a tidy schedule. Two weeks later, though, he was gone. “And that really did something to me,” Mr. Harvell said. “A person was just here, and laughing and joking, and, next thing you know, they’re not around any more.”Mr. Harvell mentioned that his own brother had died, suddenly, in 2013. Then his grandmother in 2016. Then another brother in 2018. He embalmed them all. “A lot of times, I think this is what happens to us,” he said. “The people who go on and pass away, they’ve accepted it. It’s who they leave behind, we’re not letting go.”Ms. Velazquez, in the doorway, recalled how difficult it had been when her husband died unexpectedly. People tried to talk to her, to console her. “To me, it’s just, like, just let me be,” she said. “Don’t try for nothing. It’ll go away by itself.”The room was quiet. Formaldehyde can make your eyes water and your nose run, and I was sitting in the room, burning tears on my cheeks as Mr. Harvell continued to work on the body in front of him, which had belonged to a small, slight woman. I rubbed my eyes, and Ms. Velazquez looked at me, smiling, her eyes red, too.“Aw, he’s crying for you!” she said to the body, addressing it by the woman’s name.Mr. Harvell looked up, his concentration broken for a second, and laughed. “He’s crying and he didn’t even know the lady!” he said. “See?” And he pointed to his face. “My eyes are dry.”

Read more →