Professor Young’s experiments with prairie voles revealed what poets never could: how the brain processes that fluttering feeling in the heart.Prairie voles are stocky rodents and Olympian tunnellers that surface in grassy areas to feast on grass, roots and seeds with their chisel-shaped teeth, sprouting migraines in farmers and gardeners.But to Larry Young, they were the secret to understanding romance and love.Professor Young, a neuroscientist at Emory University in Atlanta, used prairie voles in a series of experiments that revealed the chemical process for the pirouette of heart-fluttering emotions that poets have tried to put into words for centuries.He died on March 21 in Tsukuba, Japan, where he was helping to organize a scientific conference. He was 56. The cause was a heart attack, his wife, Anne Murphy, said.With their beady eyes, thick tails and sharp claws, prairie voles are not exactly cuddly. But among rodents, they are uniquely domestic: They are monogamous, and the males and females form a family unit to raise their offspring together.“Prairie voles, if you take away their partner, they show behavior similar to depression,” Professor Young told The Atlanta-Journal Constitution in 2009. “It’s almost as if there’s withdrawal from their partner.”That made them ideal for laboratory studies examining the chemistry of love.Males and female prairie voles are known to form a family unit to raise their offspring together.Todd Ahern/Emory University, via Associated PressIn a study published in 1999, Professor Young and his colleagues exploited the gene in prairie voles associated with the signaling of vasopressin, a hormone that modulates social behavior. They boosted vasopressin signaling in meadow voles, which are highly promiscuous.“With their vasopressin receptor levels boosted in this brain region,” Scientific American reported, “these normally solitary and promiscuous voles gained a new propensity to cuddle with a mate.”Headline writers were amused. “Gene Swap Turns Lecherous Mice Into Devoted Mates,” The Ottawa Citizen declared. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram: “Genetic Science Makes Mice More Romantic.” The Independent in London: “‘Perfect Husband’ Gene Discovered.”Professor Young followed up with other prairie vole studies that focused on oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates contractions during childbirth and is involved in the bonding between mothers and newborns.“Because we knew that oxytocin was involved in mother-infant bonding, we explored whether oxytocin might be involved in this partner bonding,” he said in an interview with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2019.It was.“If you take two prairie voles, a male and a female, put them together, and this time you don’t let them mate and you just give them a little bit of oxytocin, they will bond,” Professor Young said. “So that was our first set of experiments to show that oxytocin was involved in things other than maternal bonding.”He also injected female prairie voles with a drug that blocks oxytocin, which made them temporarily polygamous.“Love doesn’t really fly in and out,” Professor Young wrote in “The Chemistry Between Us: Love, Sex and the Science of Attraction” (2012, with Brian Alexander). “The complex behaviors surrounding these emotions are driven by a few molecules in our brains. It’s these molecules, acting on defined neural circuits, that so powerfully influence some of the biggest, most life-changing decisions we’ll ever make.”Professor Young always cautioned that prairie voles weren’t humans (obviously). But in the same way that mouse studies have led to medical breakthroughs, he thought his research with prairie voles had intriguing implications.“Perhaps genetic tests for the suitability of potential partners will one day become available, the results of which could accompany, and even override, our gut instincts in selecting the perfect partner,” Professor Young wrote in Nature. He added, “Drugs that manipulate brain systems at whim to enhance or diminish our love for another may not be far away.”In recent years, Professor Young was exploring whether increasing oxytocin in certain conditions would help children with autism who struggle in social interactions.Professor Young in 2021. He became interested in genetics after dissecting a fruit fly in a biochemistry class.Center for Translational Social NeuroscienceLarry James Young was born on June 16, 1967, in Sylvester, a rural town in southwest Georgia. His father, James Young, and his mother, Margaret (Giddens) Young, were peanut farmers.As a child, he had a cow named Bessie.“It was a really rural lifestyle,” Ms. Murphy said. “His aspiration was to go work at the gas station down the street and become a manager.”He attended the University of Georgia on a Pell Grant with plans to become a veterinarian. One day, in biochemistry class, he dissected a fruit fly.“And that’s when he fell in love with genetics and just wanted to figure out the genetic basis of behavior,” Ms. Murphy said. “That’s what drove him the rest of his life.”After graduating in 1989 with a degree in biochemistry, he received a Ph.D. in zoology from the University of Texas at Austin in 1994, and then took a postdoctoral position at Emory. He never left the university, eventually becoming division chief of behavioral neuroscience and psychiatric disorders at the Emory National Primate Research Center.Professor Young married Michelle Willingham in 1985; they later divorced. He married Ms. Murphy in 2002. She is a neuroscientist at Georgia State University in Atlanta.In addition to his wife, he is survived by three daughters from his first marriage, Leigh Anna, Olivia and Savannah Young; two stepsons, Jack and Sam Murphy; a brother, Terry Young; and two sisters, Marcia Young-Whitacre and Robyn Hicks.Professor Young in 2010. He predicted that one day there might be a drug that would increase the urge to fall in love.Emory UniversityAround Emory’s campus, Professor Young was also known as the Love Doctor. He was popular on Valentine’s Day — not just with Ms. Murphy. Reporters around the world would ask him to explain the chemistry of romance.One day, he said, there might even be a drug that would increase the urge to fall in love.“It would be completely unethical to give the drug to someone else,” he told The New York Times, “but if you’re in a marriage and want to maintain that relationship, you might take a little booster shot yourself every now and then.”

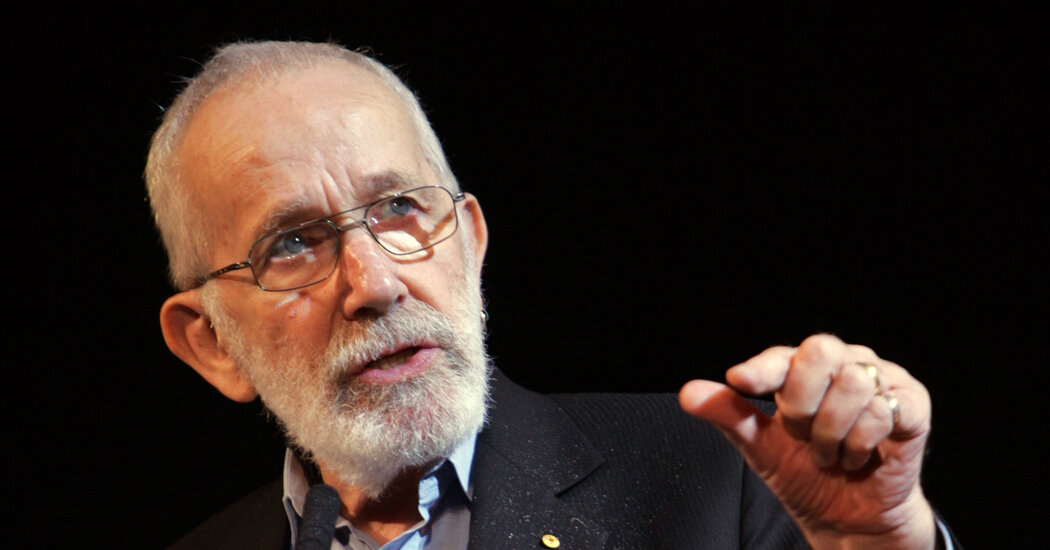

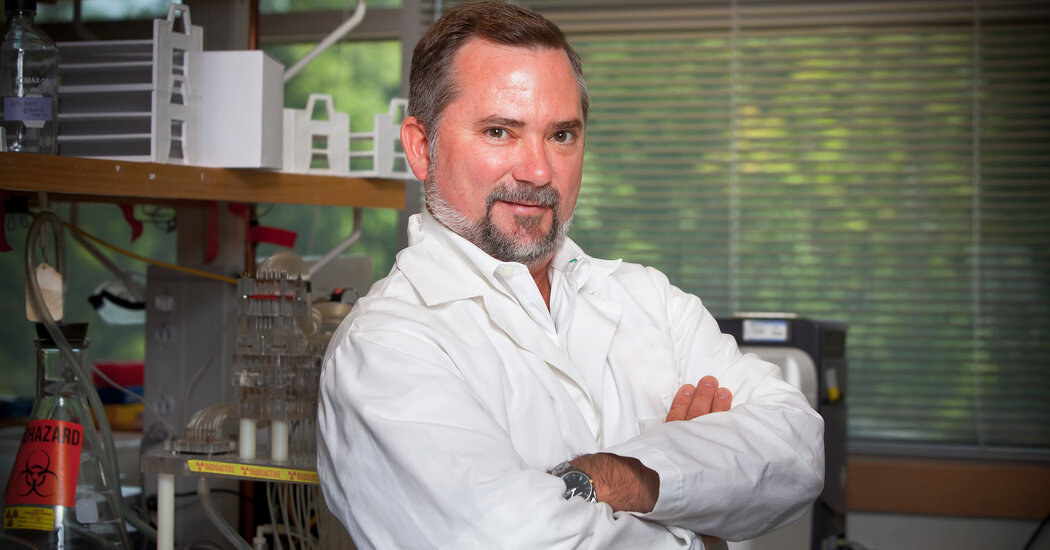

Read more →