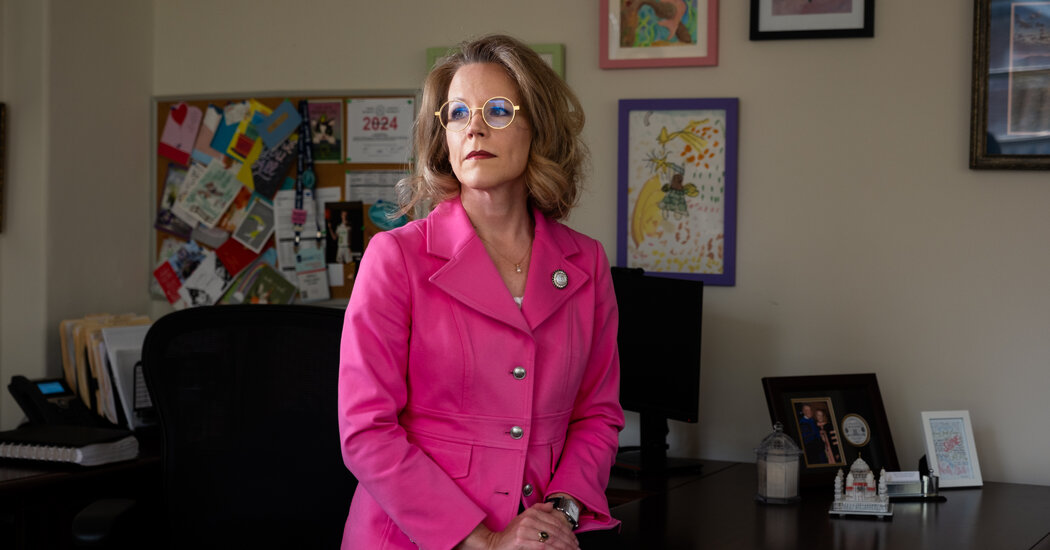

In the large budget bill now in Congress, supporters of the measure see a rare opportunity to advance a popular policy.Tens of millions of older Americans who cannot afford dental care — with severe consequences for their overall health, what they eat and even when they smile — may soon get help as Democrats maneuver to add dental benefits to Medicare for the first time in its history.The proposal, part of the large budget bill moving through Congress, would be among the largest changes to Medicare since its creation in 1965 but would require overcoming resistance from dentists themselves, who are worried that it would pay them too little.The impact could be enormous for people like Natalie Hayes, 69. Ms. Hayes worked in restaurants, raised a son and managed her health as best she could within her limited means. As she lost her teeth — most of them many years ago and her remaining front ones last fall — she simply lived with it.“I had a lot of pneumonia,” she said, at a recent visit to the Northern Counties Dental Center in Hardwick, Vt. “Not a lot of good dental care.”For Ms. Hayes, the top set of dentures she was there to get will mean the difference between smiling and not smiling — and a wider choice of food. But financially, this would never be an option if her two sisters had not pooled funds to help her. Though Medicare, the federal program primarily for people 65 and older, helped pay for her pneumonia hospitalizations and recent shoulder surgery, it does not cover dental care.For reference, she showed Colleen Mercier, a dental assistant, an old photograph.“You have a pretty smile,” Ms. Mercier saidNearly half of Americans 65 and over didn’t visit a dentist in the last year, and nearly one in five have lost all their natural teeth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There’s growing evidence that dental problems can worsen other health conditions that Medicare does cover.Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent who is the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, has played a crucial role in advancing the measure. He recalled living as a young man in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, five miles from the clinic where Ms. Hayes received her care, and learning that many residents lacked access to dentists. “A child who lived nearby, his teeth were literally rotting in his mouth,” he said.Since then, the situation in Vermont has improved. Community health centers serve about a quarter of the state’s population. The state’s Medicaid program pays for preventive care and for up to $1,000 a year in other treatment for children and poor adults. But it does not pay for dentures, which can run into the thousands of dollars. Nationwide, around half of Americans 65 and older lack any source of dental insurance.The patient, Natalie Hayes, brought in an old photo of her smile to help dentists recreate it.Kelly Burgess for The New York TimesWith so many uninsured older patients, dentists like Dr. Adrienne Rulon, who treated Ms. Hayes, practice triage. Certain teeth — like the eye teeth and first molars — are more important to save. Filling a cavity in one tooth is less expensive than a root canal in another. Sometimes, patients will come in for an exam, learn about more expensive problems, then disappear for months while they save money for the procedure. “People are having to pick and choose,” she said. “It’s a huge untreated population.”.css-1xzcza9{list-style-type:disc;padding-inline-start:1em;}.css-3btd0c{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:1rem;line-height:1.375rem;color:#333;margin-bottom:0.78125rem;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-3btd0c{font-size:1.0625rem;line-height:1.5rem;margin-bottom:0.9375rem;}}.css-3btd0c strong{font-weight:600;}.css-3btd0c em{font-style:italic;}.css-w739ur{margin:0 auto 5px;font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.125rem;line-height:1.3125rem;color:#121212;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-family:nyt-cheltenham,georgia,’times new roman’,times,serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.375rem;line-height:1.625rem;}@media (min-width:740px){#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-size:1.6875rem;line-height:1.875rem;}}@media (min-width:740px){.css-w739ur{font-size:1.25rem;line-height:1.4375rem;}}.css-9s9ecg{margin-bottom:15px;}.css-uf1ume{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-box-pack:justify;-webkit-justify-content:space-between;-ms-flex-pack:justify;justify-content:space-between;}.css-wxi1cx{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:column;-ms-flex-direction:column;flex-direction:column;-webkit-align-self:flex-end;-ms-flex-item-align:end;align-self:flex-end;}.css-12vbvwq{background-color:white;border:1px solid #e2e2e2;width:calc(100% – 40px);max-width:600px;margin:1.5rem auto 1.9rem;padding:15px;box-sizing:border-box;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-12vbvwq{padding:20px;width:100%;}}.css-12vbvwq:focus{outline:1px solid #e2e2e2;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-12vbvwq{border:none;padding:10px 0 0;border-top:2px solid #121212;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transform:rotate(0deg);-ms-transform:rotate(0deg);transform:rotate(0deg);}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-eb027h{max-height:300px;overflow:hidden;-webkit-transition:none;transition:none;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-5gimkt:after{content:’See more’;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-6mllg9{opacity:1;}.css-qjk116{margin:0 auto;overflow:hidden;}.css-qjk116 strong{font-weight:700;}.css-qjk116 em{font-style:italic;}.css-qjk116 a{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;text-underline-offset:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-thickness:1px;text-decoration-thickness:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:visited{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}Ms. Hayes was also making such judgments. A top set of dentures would give her a smile back. But she had also lost most of her bottom molars. Without a partial set of bottom dentures, she still will be unable to chew many hard foods.Poor adults in other states have even fewer resources. Medicaid is not required to cover adult dental services, and many states do not pay for any services at all, while others cover only emergency treatments, like tooth extractions. Vermont’s program is among the most generous in the nation.On Capitol Hill, the proposal to add a Medicare dental benefit has near-universal support among Democrats, and many health industry and consumer groups back it, too. The main opposition comes from dentists. With the Democrats’ large policy ambitions but narrow majority, its passage is not assured.The American Dental Association, which fought to keep dental care out of the original Medicare program in 1965, supports a limited government benefit for older Americans. The association, whose leaders say they want Congress to concentrate scarce resources on the patients who struggle the most, wants Medicare dental benefits to be offered only to poorer patients, to be offered by private insurers, and to be included in its own special part of Medicare. “Our focus is on the people who don’t go to the dentist at all,” said Michael Graham, the senior vice president for government and public affairs at the association, adding that many Medicare-eligible patients with higher incomes can already get dental care now.Medicare would most likely pay lower prices than older patients who can now afford to pay for care themselves, a potential hit to dental income. It’s possible some providers would refuse to accept Medicare.Groups that have been pushing for the provision describe this as a rare opportunity to advance a popular policy. In one recent poll, 84 percent of Americans, including more than three-quarters of Republicans, supported adding dental, vision and hearing to Medicare. While Democratic lawmakers have tended for years to embrace the idea of dental benefits, they have not made it a priority. When passing the Affordable Care Act in 2010, they chose to focus federal resources on expanding health coverage.But the $3.5 trillion package now being considered has a big enough budget for a variety of long-stalled priorities. Lawmakers hope to add not just dental benefits to Medicare, but vision and hearing coverage as well. They intend to offer Medicaid to poor adults in states that have not expanded it. They plan to extend subsidies that make Obamacare insurance less expensive for people who buy their own insurance. And they aim to broaden investments in loan repayments for health care providers who choose to practice in underserved areas like rural Vermont.The provision still faces challenges. So far, no Republicans have signed onto the plan, and negotiations are still underway among Democratic lawmakers about its size and contours. Among the various health care priorities, the dental benefit is relatively expensive — the cost estimate for a version passed by the House in 2019 was $238 billion over five years. But Melissa Burroughs, an associate director at the consumer group Families USA, who has been leading a coalition pushing for the measure, says she’s been struck by how every lawmaker she talks to wants dental coverage in the package.“It’s highly unusual,” she said. “We’ve gotten from, ‘Oh this would be good,’ to, ‘Oh this is important, and let’s take action now.’”.css-1xzcza9{list-style-type:disc;padding-inline-start:1em;}.css-3btd0c{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:1rem;line-height:1.375rem;color:#333;margin-bottom:0.78125rem;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-3btd0c{font-size:1.0625rem;line-height:1.5rem;margin-bottom:0.9375rem;}}.css-3btd0c strong{font-weight:600;}.css-3btd0c em{font-style:italic;}.css-w739ur{margin:0 auto 5px;font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.125rem;line-height:1.3125rem;color:#121212;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-family:nyt-cheltenham,georgia,’times new roman’,times,serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.375rem;line-height:1.625rem;}@media (min-width:740px){#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-size:1.6875rem;line-height:1.875rem;}}@media (min-width:740px){.css-w739ur{font-size:1.25rem;line-height:1.4375rem;}}.css-9s9ecg{margin-bottom:15px;}.css-16ed7iq{width:100%;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;justify-content:center;padding:10px 0;background-color:white;}.css-pmm6ed{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}.css-pmm6ed > :not(:first-child){margin-left:5px;}.css-5gimkt{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:0.8125rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-letter-spacing:0.03em;-moz-letter-spacing:0.03em;-ms-letter-spacing:0.03em;letter-spacing:0.03em;text-transform:uppercase;color:#333;}.css-5gimkt:after{content:’Collapse’;}.css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;-webkit-transform:rotate(180deg);-ms-transform:rotate(180deg);transform:rotate(180deg);}.css-eb027h{max-height:5000px;-webkit-transition:max-height 0.5s ease;transition:max-height 0.5s ease;}.css-6mllg9{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;position:relative;opacity:0;}.css-6mllg9:before{content:”;background-image:linear-gradient(180deg,transparent,#ffffff);background-image:-webkit-linear-gradient(270deg,rgba(255,255,255,0),#ffffff);height:80px;width:100%;position:absolute;bottom:0px;pointer-events:none;}.css-uf1ume{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-box-pack:justify;-webkit-justify-content:space-between;-ms-flex-pack:justify;justify-content:space-between;}.css-wxi1cx{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:column;-ms-flex-direction:column;flex-direction:column;-webkit-align-self:flex-end;-ms-flex-item-align:end;align-self:flex-end;}.css-12vbvwq{background-color:white;border:1px solid #e2e2e2;width:calc(100% – 40px);max-width:600px;margin:1.5rem auto 1.9rem;padding:15px;box-sizing:border-box;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-12vbvwq{padding:20px;width:100%;}}.css-12vbvwq:focus{outline:1px solid #e2e2e2;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-12vbvwq{border:none;padding:10px 0 0;border-top:2px solid #121212;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transform:rotate(0deg);-ms-transform:rotate(0deg);transform:rotate(0deg);}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-eb027h{max-height:300px;overflow:hidden;-webkit-transition:none;transition:none;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-5gimkt:after{content:’See more’;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-6mllg9{opacity:1;}.css-qjk116{margin:0 auto;overflow:hidden;}.css-qjk116 strong{font-weight:700;}.css-qjk116 em{font-style:italic;}.css-qjk116 a{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;text-underline-offset:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-thickness:1px;text-decoration-thickness:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:visited{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}For centuries, care of the mouth has been divided from care of the rest of the body. Dentists train at different schools than doctors, they accept different insurance, and the vast majority practice in private clinics where they must run their own business, not in hospitals or health centers.Northern Counties Dental Center in Hardwick, Vt. Community health centers like Northern Counties Health Care, which runs this clinic, serve about a quarter of the state’s population.Kelly Burgess for The New York TimesBut research increasingly shows how closely dental health is connected to overall health. Dental problems, and their accompanying inflammation and bacteria, can worsen other chronic conditions, like diabetes and heart disease. And missing or sore teeth can make it hard to eat a healthy diet. Dental infections can be painful — they are a major cause of emergency room visits — and, in rare cases, life-threatening.“Dental care is health care, and dental care must be part of any serious health care program in the United States,” Senator Sanders said.Medicare coverage would give older and disabled patients a way to pay for their care, yet there is no guarantee that dentists everywhere would accept it. Nearly every doctor and hospital in the country takes Medicare, but dentists have built their businesses over the last 50 years without relying on the program. Many dentists in private practice refuse to accept Medicaid, saying that payments are too low and the red tape burden too high.“If you provide somebody with a covered benefit and they have no place to go, then that’s feckless,” said Tess Kuenning, the president of Bistate Primary Care Association, a group for community health centers in Vermont and New Hampshire. Ms. Kuenning urged lawmakers to ensure payment rates that would be enticing to dentists, and investments in public health dentists like Dr. Rulon, who would be more inclined than dentists in private practices to treat Medicare patients.But optimists see Medicare dental coverage as something that might do more than just improve affordability for beneficiaries. It could also shift longstanding norms about what health insurance should cover. Historically, health plans have tended to ignore health problems “in your head”: omitting dental coverage, vision benefits, hearing aids and mental health. Congress began requiring mental health coverage about 15 years ago, starting in Medicare, and then expanding to other types of plans. Mental health care access is still uneven, but has become more broadly understood to be a part of health care.“When Medicare moves, everyone else moves,” said Michael Costa, the C.E.O. at Northern Counties Health Care and a former top health policy official for Vermont.In the meantime, Medicare patients treated in Hardwick continue to make tough choices. When Gina Brown, 66, came in recently for a teeth cleaning, Dr. Rulon discovered a cavity near a root — one that could quickly cost her the tooth. She was back in the chair for a filling that afternoon. She had comprehensive health coverage through her job caring for developmentally disabled adults, she said, but her dental benefit was “very limited.” She could afford to fix this ailing front tooth, but not a partial denture to replace the molars she had lost years ago, when money was tight and dental care out of reach.“Maybe if I had some dental insurance, I might think about getting a partial,” she said, as she waited for the Novocain to kick in.

Read more →