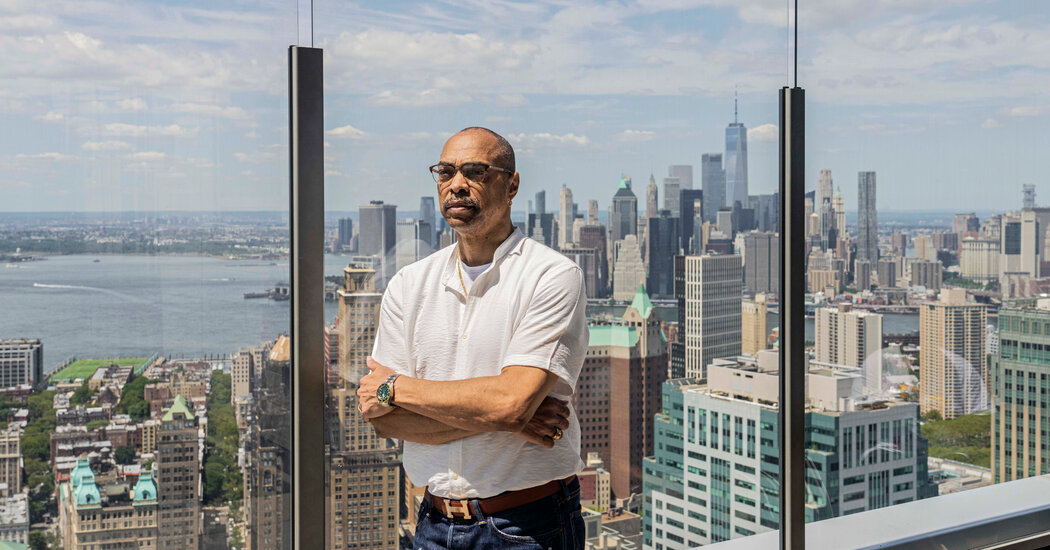

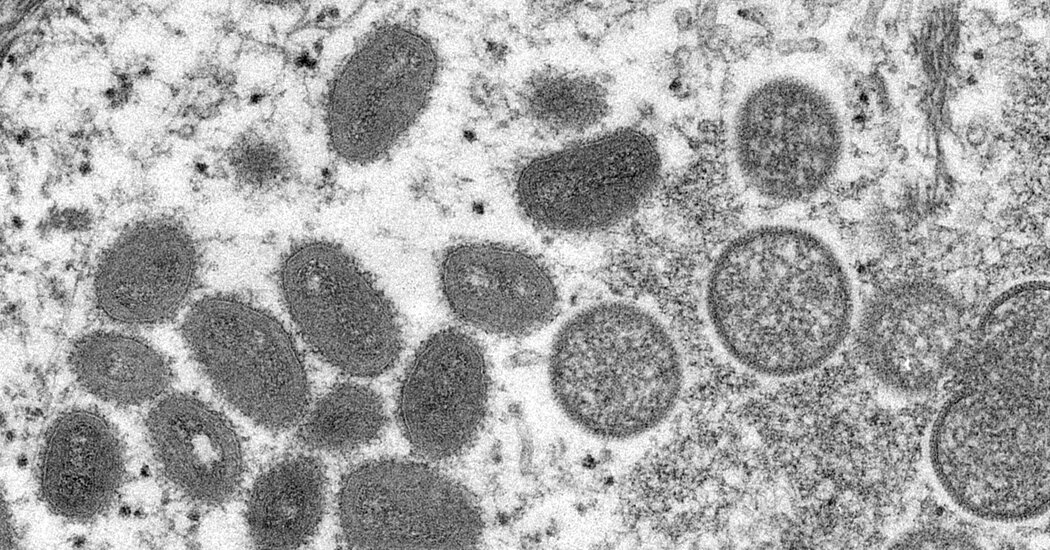

Patients will be asked if their genetic sequence can be added to a database — shared with a pharmaceutical company — in a quest to cure a multitude of diseases.The Mount Sinai Health System began an effort this week to build a vast database of patient genetic information that can be studied by researchers — and by a large pharmaceutical company.The goal is to search for treatments for illnesses ranging from schizophrenia to kidney disease, but the effort to gather genetic information for many patients, collected during routine blood draws, could also raise privacy concerns.The data will be rendered anonymous, and Mount Sinai said it had no intention of sharing it with anyone other than researchers. But consumer or genealogical databases full of genetic information, such as Ancestry.com and GEDmatch, have been used by detectives searching for genetic clues that might help them solve old crimes.Vast sets of genetic sequences can unlock new insights into many diseases and also pave the way for new treatments, researchers at Mount Sinai say. But the only way to compile those research databases is to first convince huge numbers of people to agree to have their genomes sequenced.Beyond chasing the next breakthrough drug, researchers hope the database, when paired with patient medical records, will provide new insights into how the interplay between genetic and socio-economic factors — such as poverty or exposure to air pollution — can affect people’s health.“This is really transformative,” said Alexander Charney, a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who is overseeing the project.The health system hopes to eventually amass a database of genetic sequences for 1 million patients, which would mean the inclusion of roughly one out of every 10 New York City residents. The effort began this week, a hospital spokeswoman, Karin Eskenazi, said.This is not Mount Sinai’s first attempt to build a genetics database. For some 15 years, Mount Sinai has been slowly building a bank of biological samples, or biobank, called BioMe, with about 50,000 DNA sequences so far. However, researchers have been frustrated at the slow pace, which they attribute to the cumbersome process they use to gain consent and enroll patients: multiple surveys, and a lengthy one-on-one discussion with a Mount Sinai employee that sometimes runs 20 minutes, according to Dr. Girish Nadkarni of Mount Sinai, who is leading the project along with Dr. Charney.Most of that consent process is going by the wayside. Mount Sinai has jettisoned the health surveys and boiled down the procedure to watching a short video and providing a signature. This week it began trying to enroll most patients who were receiving blood tests as part of their routine care.A number of large biobank programs already exist across the country. But the one that Mount Sinai Health System is seeking to build would be the first large-scale one to draw participants primarily from New York City. The program could well mark a shift in how many New Yorkers think about their genetic information, from something private or unknown to something they’ve donated to research.The project will involve sequencing a huge number of DNA samples, an undertaking that could cost tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. To avoid that cost, Mount Sinai has partnered with Regeneron, a large pharmaceutical company, that will do the actual sequencing work. In return, the company will gain access to the genetic sequences and partial medical records of each participant, according to Mount Sinai doctors leading the program. Mount Sinai also intends to share data with other researchers as well.Though Mount Sinai researchers have access to anonymized electronic health records of each patient who participates, the data shared with Regeneron will be more limited, according to Mount Sinai. The company may access diagnoses, lab reports and vital signs.When paired with health records, large genetic datasets can help researchers search out rare mutations that either have a strong association with a certain disease, or may protect against it.It remains to be seen if Mount Sinai, among the city’s largest hospital systems, can reach its target of enrolling a million patients in the program, which the hospital is calling the “‘Mount Sinai Million Health Discoveries Program.” If it does, the resulting database will be among the largest in the country, alongside one run by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs as well as a project run by the National Institutes of Health that has the goal of eventually enrolling 1 million Americans, though it is currently far short.(Those two government projects involve whole-genome sequencing, which reveal an individual’s complete DNA makeup; the Mount Sinai project will sequence about 1 percent of each individual’s genome, called the exome.)A health system in northeast Pennsylvania, Geisinger Health System, has also built a database of more than 185,000 DNA sequences, through a partnership with Regeneron. That database played a role in the discovery of mutations that can protect against obesity and fatty liver disease.Mt. Sinai Health System, in partnership with a pharmaceutical company, is planning to build a massive database of patient genetic information to be used in research.Spencer Platt/Getty ImagesRegeneron, which in recent years became widely known for its effective monoclonal antibody treatment for Covid-19, has sequenced and studied the DNA of approximately 2 million “patient volunteers,” mainly through collaborations with health systems and a large biobank in Britain, according to the company.But the number of patients Mount Sinai hopes to enroll — coupled with their racial and ethnic diversity, and that of New York City generally — would set it apart from most existing databases.“The scale and the type of discoveries we’ll all be able to make is quite different than what’s possible up until today with smaller studies,” said Dr. Aris Baras, a senior vice president at Regeneron.People of European ancestry are typically overrepresented in genomic datasets, which means, for example, that genetic tests people get for cancer risk are far more attuned to genetic variants that are common among white cancer patients, Dr. Baras said.“If you’re not of European ancestry, there is less information about variants and genes and you’re not going to get as good a genetic test as a result of that,” Dr. Baras said.Mount Sinai Health System, which has seven hospitals in New York City, sees about 1.1 million individual patients a year and handles more than 3 million outpatient visits to doctor’s offices. Dr. Charney estimated that the hospital system was drawing the blood of at least 300,000 patients annually, and he expected many of them to consent to having their blood used for genetic research.The enrollment rate for such data collection is usually high — around 80 percent, he said. “So the math checks out. We should be able to get to a million.”Mark Gerstein, a professor of Biomedical Informatics at Yale University, said there was no question that genomic datasets were driving great medical discoveries. But he said he still would not participate in one himself, and he urged people to consider whether adding their DNA to a database might someday affect their grandchildren.“I tend to be a worrier,” he said.Our collective knowledge of mutations and what illnesses they are associated with — whether Alzheimer’s or schizophrenia — would only increase in the years ahead, he said. “If the datasets leaked some day, the information might be used to discriminate against the children or grandchildren of current participants,” Dr. Gerstein said. They might be teased or denied insurance, he added.He noted that even if the data was anonymous and secure today, that could change. “Securing the information over long periods of time gets much harder,” he said, noting that Regeneron might not even exist in 50 years. “The risk of the data being hacked over such a long period of time becomes magnified,” he said.Other doctors urged participation, noting genetic research offered great hope for developing treatments for a range of maladies. Dr. Charney, who will oversee the effort to amass a million sequences, studies schizophrenia. He has used Mount Sinai’s existing database to search for a particular gene variant associated with psychotic illness.Of the three patients in the existing Mount Sinai BioMe database with that variant, only one had a severe lifelong psychotic illness. “What is it about the genomes of these other two people that somehow protected them, or maybe it’s their environment that protected them?” he asked.His team has begun calling those patients in for additional research. The plan is to take samples of their cells and use gene-editing technology to study the effect of various changes to this particular genetic variant. “Essentially what we’re saying is: ‘what is schizophrenia in a dish?’” Trying to answer that question, Dr. Charney said, “can help you hone in on what is the actual disease process.”Wilbert Gibson, 65, is enrolled in Mount Sinai’s existing genetic database. Healthy until he reached 60, his heart began to fail rapidly, but doctors initially struggled with a diagnosis. At Mount Sinai, he discovered that he suffered from cardiac amyloidosis, in which protein builds up in the heart, reducing its ability to pump blood.He received a heart transplant. When he was asked if he would share his genome to help research, he was happy to oblige. He was included in genetics research that helped identify a gene variant in people of African descent linked to heart disease. Participating in medical research was the easiest decision he faced at the time.“When you’re in the situation I’m in and find your heart is failing, and everything is happening so fast, you go and do it,” he said in an interview in which he credited the doctors at Mount Sinai with saving his life.

Read more →