The Fight Over Abortion History

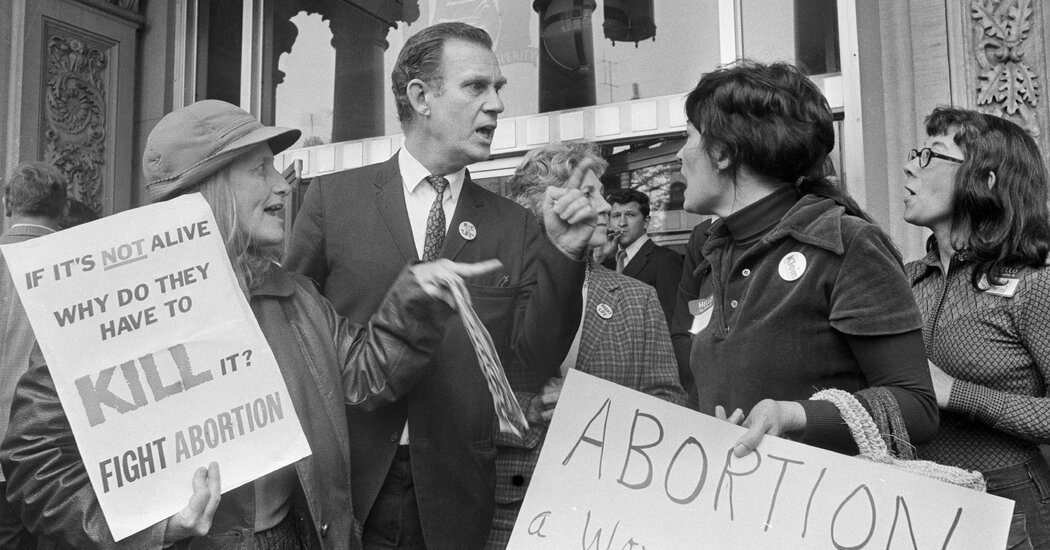

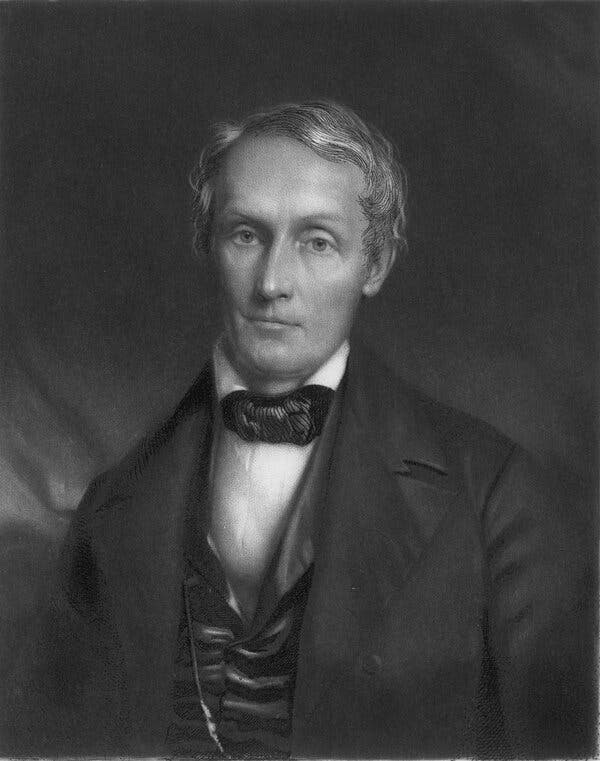

The leaked draft opinion that would overturn Roe v. Wade also takes aim at its version of history, challenging decades of scholarship that argues abortion was not always a crime.History, and arguments about history, have long been central to abortion jurisprudence.In its 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court found a constitutional right to abortion, grounded in what it described as a “right to privacy” provided in the Fourteenth Amendment. And that legal argument was bolstered by a historical narrative.State laws prohibiting abortion at all stages of pregnancy, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote in the opinion, were not of ancient or even common-law origin, but dated mostly to the late 19th century. Before that, he wrote, citing various scholars, abortion early in pregnancy was legal in most states.The leaked draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which would overturn Roe, offers a very different history. The 98-page draft, written by Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., asserts that “an unbroken tradition of prohibiting abortion on pain of criminal punishment persisted from the earliest days of the common law until 1973.”Roe, Justice Alito writes, “either ignored or misstated this history.” And “it is therefore important,” he continues, “to set the record straight.”The claim of an “unbroken tradition” of criminalizing abortion set off strong criticism from many historians, including some whose work was cited in an amicus brief submitted by the American Historical Association and the Organization of American Historians, the two main organizations of professional historians in the United States.Here are some of the historical claims in question.Justice Alito on the History of Abortion RestrictionsJustice Alito begins his historical argument by saying that the right to abortion is a recent invention. “Until the latter part of the 20th century,” he writes, “there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. Zero. None.”By contrast, he claims, “abortion had long been a crime in every single state.” Until the 19th century, he maintains, American law followed common law, which criminalized abortion “in at least some stages of pregnancy.” And the records of prosecutions, however scant, “corroborate that abortion was a crime.”In the 1800s, he writes, states began passing laws that “expanded criminal liability.” By the time the 14th Amendment was adopted, three-quarters of the states outlawed abortion at all stages of pregnancy, with the rest to follow within a few decades.How Historians See the StoryThe Constitution includes no references to abortion. And it wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century, Justice Alito writes, that people began claiming the idea of a basic right to abortion.Mary Ziegler, the author of several books on the history of abortion (and a critic of the draft decision), said that part was correct. But the opinion, she and others argue, underplays the fact that for most of the first 100 years of American history, early abortions — before fetal “quickening” (generally defined as the moment when the fetus’s movements can be detected) — were not illegal.This is the argument made in the historians’ brief, which outlines the history of abortion regulation up to 1866. For decades after the founding of the United States, common law did not regulate abortion, or even recognize that abortion was happening at that early stage. “That is because common law did not even acknowledge a fetus as existing separately from a pregnant woman” before quickening, the historians argue.The central historical claims in Roe “were accurate,” the brief says, “and remain so today.”Leslie J. Reagan, the author of “When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine and Law in the United States, 1867 to 1973,” said in an interview that abortion was common in the early 19th century, perhaps even more so than Roe depicted.And regulation relied on women’s own experience, since they were the ones who would know when “quickening” occurred. And before “quickening,” Professor Reagan said, taking medications or other treatments wasn’t even considered abortion, but “trying to get your menses” — menstrual period — “back.”“It was after quickening that it was against the law, and considered immoral,” she said. “After quickening, women themselves would stop trying to get their menses back. It was considered a life.”Justice Alito’s SourcesWhile the draft makes references to the historians’ brief, it relies more heavily on other sources, including “Dispelling the Myths of Abortion History,” a 2006 book by Joseph W. Dellapenna that challenged Justice Blackmun’s historical arguments in Roe.Professor Dellapenna, a law professor at Villanova University, cited (using a phrase Justice Alito echoes in the draft opinion) what he called an “unbroken tradition” of laws protecting unborn life, which stretched from English common law into the 1970s.His book has been hotly debated by historians. But Justice Alito also draws on other sources, including a brief submitted by the legal scholars Robert P. George and John M. Finnis, who challenged the historical scholarship supporting Roe.By the late 1860s, they argue, the legal distinction of “quickening” had been abandoned, “because science had shown that a distinct human being begins at conception.” When the Fourteenth Amendment was passed in 1868, they argue, fetuses were understood as “persons” deserving protection.In a post on Tuesday in Mirror of Justice, a Catholic legal blog, Professor George wrote that the term “person” in the Fourteenth Amendment “was publicly understood at the time of the framing and ratification of the amendment as including the child in the womb.”He added on Twitter that “bizarrely, some critics of the leaked Alito opinion in Dobbs are trying to cast doubt on his historiography by reviving discredited claims” about abortion history included in Roe, claims he said he and Finnis had “refuted.”In a telephone interview, he declined to comment further on the substance of the draft opinion, calling the leak a highly damaging breach of trust. But he said that history had always been crucial to the abortion debate, since analysis of history was “at the core of Roe.”By focusing on history, Professor George said, Blackmun was able to claim — falsely, he said — “that the Court wasn’t inventing a new right, but restoring an old common-law right.”How Abortion Restrictions Changed Over TimeIn 1827, Illinois became the first state to criminalize abortions pre-quickening. In 1829, New York elevated the offense from a misdemeanor to a felony.These laws were driven by various motivations. According to the historians’ brief, the stricter statutes enacted through the 1840s and 1850s “were often in response to alarming newspaper stories about women’s deaths from abortions. Yet despite these new laws on the books,” the brief says, “abortion convictions remained rare.”This echoes Professor Reagan’s book, which argues (citing the historian James C. Mohr) that the earliest laws regulating abortion were poison-control measures meant to protect women from dangerous abortifacient drugs, rather than to restrict abortion itself.But in 1857, Professor Reagan writes, the newly founded American Medical Association “initiated a crusade to make abortion at every stage of pregnancy illegal.” The organization was driven not only by concern for fetal life but also by the desire to take control from midwives. And some members expressed concern that middle-class “Anglo-Saxon” women were not having as many children as Catholic immigrants and people of color.Dr. Horatio R. Storer, a leader of the medical campaign against abortion, asked who would settle the nation as it spread westward. Would the frontier “be filled by our own children or by those of aliens?” he asked. “This is a question that our own women must answer; upon their loins depends the future destiny of the nation.”Debating the Connections Between Abortion and RaceIn the draft opinion, Justice Alito notes the argument that the restrictive abortion laws adopted starting in the mid-19th century were meant to bolster the white, Protestant birthrate. But he dismisses the claim, saying it is based on only a handful of supporters of abortion bans. “It’s quite a leap to attribute these motives to all the legislators whose votes were responsible” for the new laws, he writes.Instead, he writes, “there is ample evidence” that anti-abortion laws were “spurred by a sincere belief that abortion kills a human being.”Instead, Justice Alito notes arguments that proponents of abortion rights were the ones with racist motives. In a footnote, he refers to an amicus brief submitted in an unrelated 2019 abortion case, which argued that early 20th-century proponents of “liberal access to abortion” were motivated by a desire to reduce the Black population.“It is beyond dispute that Roe has had that demographic effect,” Justice Alito writes, citing government data showing that “a highly disproportionate percentage of aborted fetuses are Black.”He also cites Justice Clarence Thomas’s much-noted fiery concurrence in that 2019 abortion case, in which he assailed early birth control advocates like Margaret Sanger as racist eugenicists who wanted to suppress the births of “undesirable” individuals and populations.While Sanger herself did not support abortion, Justice Thomas wrote, other family planning advocates did so “for eugenic reasons.” And today, he warned, abortion retains the potential “to become a tool of eugenic manipulation.”The historical relationship between the early family planning movement and eugenicist beliefs (which were widely held across American society in the early 20th century) is complex and intensely disputed.But Professor Ziegler questioned how Justice Alito could dismiss the notion that abortion restrictionists in the 1850s were motivated even in part by bigotry, while citing claims that it was a motivation of some 20th-century supporters of abortion.People on both sides of the issue, she said, were driven by a mix of motives. “The idea the Court thinks it can weed out the nativist impulses” on one side, while emphasizing those impulses on the other, she said, “is historically implausible.”

Read more →