Learning to Love G.M.O.s

Listen to This ArticleAudio Recording by AudmTo hear more audio stories from publications like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android.On a cold December day in Norwich, England, Cathie Martin met me at a laboratory inside the John Innes Centre, where she works. A plant biologist, Martin has spent almost two decades studying tomatoes, and I had traveled to see her because of a particular one she created: a lustrous, dark purple variety that is unusually high in antioxidants, with twice the amount found in blueberries.At 66, Martin has silver-white hair, a strong chin and sharp eyes that give her a slightly elfin look. Her office, a tiny cubby just off the lab, is so packed with binders and piles of paper that Martin has to stand when typing on her computer keyboard, which sits surrounded by a heap of papers like a rock that has sunk to the bottom of a snowdrift. “It’s an absolute disaster,” Martin said, looking around fondly. “I’m told that the security guards bring people round on the tour.” On the desk, there’s a drinks coaster with a picture of an attractive 1950s housewife that reads, “You say tomato, I say [expletive] you.”Martin has long been interested in how plants produce beneficial nutrients. The purple tomato is the first she designed to have more anthocyanin, a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory compound. “All higher plants have a mechanism for making anthocyanins,” Martin explained when we met. “A tomato plant makes them as well, in the leaves. We just put in a switch that turns on anthocyanin production in the fruit.” Martin noted that while there are other tomato varieties that look purple, they have anthocyanins only in the skin, so the health benefits are slight. “People say, Oh, there are purple tomatoes already,” Martin said. “But they don’t have these kind of levels.”The difference is significant. When cancer-prone mice were given Martin’s purple tomatoes as part of their diet, they lived 30 percent longer than mice fed the same quantity of ordinary tomatoes; they were also less susceptible to inflammatory bowel disease. After the publication of Martin’s first paper showing the anticancer benefit of her tomatoes, in the academic journal Nature Biotechnology in 2008, newspapers and television stations began calling. “The coverage!” she recalled. “Days and days and days and days of it! There was a lot of excitement.” She considered making the tomato available in stores or offering it online as a juice. But because the plant contained a pair of genes from a snapdragon — that’s what spurs the tomatoes to produce more anthocyanin — it would be classified as a genetically modified organism: a G.M.O.That designation brings with it a host of obligations, not just in Britain but in the United States and many other countries. Martin had envisioned making the juice on a small scale, but just to go through the F.D.A. approval process would cost a million dollars. Adding U.S.D.A. approval could push that amount even higher. (Tomato juice is known as a “G.M. product” and is regulated by the F.D.A. Because a tomato has seeds that can germinate, it is regulated by both the F.D.A. and the U.S.D.A.) “I thought, This is ridiculous,” Martin told me.Martin eventually did put together the required documentation, but the process, and subsequent revisions, took almost six years. “Our ‘business model’ is that we have this tiny company which has no employees,” Martin said with a laugh. “Of course, the F.D.A. is used to the bigger organizations” — global agricultural conglomerates like DowDuPont or Syngenta — “so this is where you get a bit of a problem. When they say, ‘Oh, we want a bit more data on this,’ it’s easy for a corporation. For me — it’s me that has to do it! And I can’t just throw money at it.”Martin admitted that, as an academic, she hadn’t been as focused on getting the tomato to market as she might have been. (Her colleague Jonathan Jones, a plant biologist, eventually stepped in to assist.) But the process has also been slow because the purple tomato, if approved, would be one of only a very few G.M.O. fruits or vegetables sold directly to consumers. The others include Rainbow papayas, which were modified to resist ringspot virus; a variety of sweet corn; some russet potatoes; and Arctic Apples, which were developed in Canada and resist browning.It also might be the first genetically modified anything that people actually want. Since their introduction in the mid-1990s, G.M.O.s have remained wildly unpopular with consumers, who see them as dubious tools of Big Ag, with potentially sinister impacts on both people and the environment. Martin is perhaps onto something when she describes those most opposed to G.M.O.s as “the W.W.W.s”: the well, wealthy and worried, the same cohort of upper-middle-class shoppers who have turned organic food into a multibillion-dollar industry. “If you’re a W.W.W., the calculation is, G.M.O.s seem bad, so I’m just going to avoid them,” she said. “I mean, if you think there might be a risk, and there’s no benefit to you, why even consider it?”The purple tomato could perhaps change that calculation. Unlike commercial G.M.O. crops — things like soy and canola — Martin’s tomato wasn’t designed for profit and would be grown in small batches rather than on millions of acres: essentially the opposite of industrial agriculture. The additional genes it contains (from the snapdragon, itself a relative of the tomato plant) act only to boost production of anthocyanin, a nutrient that tomatoes already make. More important, the fruit’s anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties, which seem considerable, are things that many of us actively want.Nonetheless, the future of the purple tomato is far from certain. “There’s just so much baggage around anything genetically modified,” Martin said. “I’m not trying to make money. I’m worried about people’s health! But in people’s minds it’s all Dr. Frankenstein and trying to rule the world.”Bobby Doherty for The New York TimesIn the three decades since G.M.O. crops were introduced, only a tiny number have been developed and approved for sale, almost all of them products made by large agrochemical companies like Monsanto. Within those categories, though, G.M.O.s have taken over much of the market. Roughly 94 percent of soybeans grown in the United States are genetically modified, as is more than 90 percent of all corn, canola and sugar beets, together covering roughly 170 million acres of cropland.At the same time, resistance to G.M.O. foods has only become more entrenched. The market for products certified to be non-G.M.O. has increased more than 70-fold since 2010, from roughly $350 million that year to $26 billion by 2018. There are now more than 55,000 products carrying the “Non-G.M.O. Project Verified” label on their packaging. Nearly half of all U.S. shoppers say that they try not to buy G.M.O. foods, while a study by Jennifer Kuzma, a biochemist who is a director of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center at North Carolina State University, found that consumers will pay up to 20 percent more to avoid them.For many of us, the rejection of G.M.O.s is instinctive. “For people who are uncomfortable with this, the objection is that it isn’t something that would ever happen in nature,” says Alan Levinovitz, a professor of religion and science at James Madison University. “With genetic engineering, there’s a feeling that we’re mucking about with the essential building blocks of reality. We may feel OK about rearranging genes, the way nature does, but we’re not comfortable mixing them up between creatures.”Our distrust might also stem from the way G.M.O.s were introduced. When the agribusiness giant Monsanto released its first G.M.O. crop in 1996 — an herbicide-resistant soybean — the company was in need of cash. By adding a gene from a bacterium, it hoped to create crops that were resistant to glyphosate, the active ingredient in its trademark herbicide, RoundUp, enabling farmers to spray weeds liberally without also killing the soy plant itself — something that wasn’t possible with traditional herbicides. Commercially, the idea succeeded. By 2003, RoundUp Ready corn and soy seeds dominated the market, and Monsanto had become the largest producer of genetically engineered seeds, responsible for more than 90 percent of G.M.O. crops planted globally.But the company’s rollout also alarmed and antagonized farmers, who were required to sign restrictive contracts to use the patented seeds, and whom Monsanto aggressively prosecuted. At one point, the company had a 75-person team dedicated solely to investigating farmers suspected of saving seed — a traditional practice in which seeds from one year’s crop are saved for planting the following year — and prosecuting them on charges of intellectual-property infringement. Environmental groups were also concerned, because of the skyrocketing use of RoundUp and the abrupt decline in agricultural diversity.“It was kind of a perfect storm,” says Mark Lynas, an environmental writer and activist who protested against G.M.O.s for over a decade. “You had this company that had made Agent Orange and PCBs” — an environmental toxin that the E.P.A. banned in 1979 — “that was now using G.M.O.s to intensify the worst forms of monoculture farming. I just remember feeling like we had to stop this thing.”That resistance was compounded because early G.M.O.s — which focused largely on pest- and herbicide-resistance — offered little direct benefit to the consumer. And once public sentiment was set, it proved hard to shift, even when more beneficial products began to emerge. One of these, Golden Rice, was made in 1999 by a pair of university researchers hoping to combat vitamin A deficiency, a simple but devastating ailment that causes blindness in millions of people in Africa and Asia annually, and that can also be fatal. But the project foundered after protests by anti-G.M.O. activists in the United States and Europe, which in turn alarmed governments and populations in developing countries.“Probably the angriest I’ve ever felt was when anti-G.M.O. groups destroyed fields of Golden Rice growing in the Philippines,” says Lynas, who publicly disavowed his opposition to G.M.O.s in 2013. “To see a crop that had such obvious lifesaving potential ruined — it would be like anti-vaxxer groups invading a laboratory and destroying a million vials of Covid vaccine.”In recent years, many environmental groups have also quietly walked back their opposition as evidence has mounted that existing G.M.O.s are both safe to eat and not inherently bad for the environment. The introduction of Bt corn, which contains a gene from Bacillus thuringiensis, a naturally insect-resistant bacterium that organic farmers routinely spray on crops, dropped the crop’s insecticide use by 35 percent. A pest-resistant Bt eggplant has become similarly popular in Bangladesh, where farmers have also embraced flood-tolerant “scuba rice,” a variety engineered to survive being submerged for up to 14 days rather than just three. Each year, Bangladesh and India lose roughly four million tons of rice to flooding — enough to feed 30 million people — and waste a corresponding volume of pesticides and herbicides, which then enter the groundwater.In North America, though, such benefits can seem remote compared with what we think of as “eating naturally.” That’s especially true because, for many of us, G.M.O.s and the harms of industrial agriculture (monocultures, overuse of pesticides and herbicides) remain inextricably linked. “Because of the way that G.M.O.s were introduced to the public — as a corporate product, focused on profit — the whole technology got tarred,” Lynas says. “In people’s minds it’s ‘Genetic engineering equals monoculture equals the broken food system.’ But it doesn’t have to be that way.”Bobby Doherty for The New York TimesThe greenhouse where Martin grows her tomatoes is surprisingly modest: a small and somewhat grubby building filled with leggy plants in plastic pots. Martin often has multiple projects going at one time, and as she walked me down the row, she pointed out a (non-G.M.O.) tomato bred to be rich in vitamin D; another with high levels of resveratrol, the antioxidant compound in red wine; and one that a postdoc, Eugenio Butelli, is trying to modify to produce serotonin, a neurotransmitter used in antidepressant drugs. When I asked whether antidepressant tomatoes were next, Martin shrugged. “He’s playing,” she said. “A lot of what we do is play.”Even if the serotonin-producing tomatoes proved possible, she added, they wouldn’t be sold in grocery stores but would simply be added to the growing list of “biologics”: plants or bacteria that have been genetically engineered to produce the active ingredient in medications, including ones for diabetes, breast cancer and arthritis. Martin herself recently created a tomato that produces levodopa, the primary drug for treating Parkinson’s disease, in hopes of making the drug both more affordable and more tolerable. (The synthetic version of levodopa can cause nausea and other side effects, and it also costs about $2 a day — more than some patients, especially those in developing countries, can afford.)Farther down the row was the next-generation purple tomato: a dark blue-black variety called Indigo that Martin has created by crossing the high-anthocyanin purple tomato with a yellow one high in flavonols, an anti-inflammatory compound found in things like kale and green tea, making it even richer in antioxidants. The Indigo, which is also a G.M.O., is too new to have been evaluated for health benefits, but Martin is hopeful that it will have even more robust health effects than the purple tomato.One pot over, Martin stopped at a purple-tomato plant hung with a single luscious cluster of fruit. “There’s a lovely one,” Martin said, picking it gently and brushing off a few white flecks. “Interestingly, the high-anthocyanin tomatoes also have an extended shelf life. We’re not sure why, but they seem to be more resistant to fungal infection, which is what causes tomatoes to rot.”Such unanticipated genetic changes can cut both ways, of course. In 1996, researchers determined that soybeans containing a gene from a Brazil nut could trigger a reaction in someone who is allergic. (The soybeans were experimental and never intended for the market.) Likewise, instead of lasting longer, Martin’s tomato could have turned mealy or become more bitter. Theoretically, it could even have become dangerous. Had Martin added genes that increased production of solanine — a toxic chemical produced by plants in the nightshade family, including tomatoes and potatoes — the resulting fruit could have been lethal.For anyone wondering, I sampled Martin’s purple and Indigo tomatoes, and eating them has so far not had any alarming effects, at least that I can detect. But of course, I can’t say for sure. What if genetically modified produce turns out to have delayed or unpredictable consequences for our health? Something we can’t easily observe or test for, or perhaps even detect until it’s too late?The fear of such unforeseen effects — what Kuzma calls “unknowingness” — is perhaps consumers’ biggest concern when it comes to G.M.O.s. Genetic interactions, after all, are famously complex. Adding a new gene — or simply changing how a gene is regulated (i.e., how active it is) — rarely affects just a single thing. Moreover, our understanding of these interactions, and their effects, is constantly evolving. Megan Westgate, executive director of the Non-G.M.O. Project, echoed this point. “Anyone who knows about genetics knows that there’s a lot we don’t understand,” Westgate says. “We’re always discovering new things or finding out that things we believed aren’t actually right.” Charles Benbrook, executive director of the Heartland Health Research Alliance, also notes that any potential health impacts from G.M.O.s would be stronger in whole foods — produce we consume raw, unprocessed and in large amounts — than in ingredients like corn syrup.‘For the majority of people, the anxiety around G.M.O.s is almost entirely untethered to an understanding of what’s happening at a scientific level.’Despite that, plant geneticists tend not to be overly concerned about the risks of G.M.O.s, as long as the modifications are made with some care. As a 2016 report by the National Academy of Sciences found, G.M.O.s were generally safe, though it allowed that minor impacts were theoretically possible. Fred Gould, a professor of agriculture who was chairman of the committee that prepared the 600-page report, noted that genetic changes that alter a metabolic pathway — the cellular process that transforms biochemical elements into a particular nutrient or compound, like the anthocyanins in Martin’s tomato — were especially important to study because they could cause cascading effects.Gould likened these pathways to the plumbing in a house. If a genetic edit shuts off one pipe — say one that generates a bitter compound — the building blocks for that compound will start flowing elsewhere, the way a blocked pipe will force water into neighboring channels. The results of this redirection, Gould told me, are poorly understood. “Do the extra precursor chemicals end up producing more of something else?” Gould asked. “Or do they just stay as precursors? For some pathways, plant biologists know the answer. But in other cases we don’t.”But he also noted that this problem wasn’t unique to G.M.O.s. Years ago, for instance, farmers crossbred cucumbers to reduce the amount of cucurbitacin (a bitter compound that repels spider mites) in the peel. But because those cucumbers were made with conventional breeding, growers weren’t required to sequence the genome of the new variety, or even to look at its nutritional and toxicity profile, as they would with something genetically engineered. “We’ve never really asked a conventional breeder: ‘Hey, when you turn off the production of cucurbitacin by crossbreeding, does something else get produced?’” Gould added. “Or do the levels of other important compounds go up or down?”Gould emphasized that many genetic modifications to food are trivial and extremely unlikely to have any measurable effect on people. And even the effects of precursor changes would mostly be slight. “I mean, we’ve been changing all these things already with conventional breeding, and so far we’re doing all right,” he added. “Making the same change with genetic engineering — there’s really no difference.”Bobby Doherty for The New York TimesIf we don’t find these sorts of distinctions very reassuring, it’s in part because our extravagant concern about G.M.O.s reflects something more fundamental: the fact that most of us don’t really understand how genes work. As several scientists I spoke with pointed out, a gene is just a narrow set of biological instructions, many of which appear across a wide range of species. The snapdragon gene in Martin’s tomato, for instance, is known as a transcription factor: essentially, a kind of volume knob that regulates how much of something a particular gene will produce. That something could be anthocyanin, or it could be a dangerous toxin, but the knob itself isn’t the problem, nor is the process by which it was added. “For the majority of people, the anxiety around G.M.O.s is almost entirely untethered to an understanding of what’s happening at a scientific level,” Levinovitz says. “But that actually makes the anxiety harder to address, rather than easier.”This is particularly true around food. Whether or not people actually understand where their fruits and vegetables come from, Levinovitz says, we think that we do — and are disturbed when that changes. The philosophical term for this is epistemic opacity. “When you imagine you know how something works, or where it comes from, that’s comforting,” he added. “So when you hear that an apple was genetically modified, it’s like, What does that mean? It’s alienating.”For many consumers, Levinovitz notes, the word “natural” has become a heuristic: a mental shortcut for deciding if something is good or safe. “We hear it all the time, and it is often true. Why do we have chronic pain? Because we weren’t meant to sit at a desk for hours. Why is the sea turtle not reproducing? Because of the artificial light we introduced on beaches. It’s not a very consistent view” — there are all kinds of unnatural things that nobody worries about, like Netflix and indoor plumbing — “but it’s become a kind of shorthand for this world we feel like we’ve lost.”In practice, of course, almost everything we grow and eat today has had its DNA altered extensively. For millenniums, farmers, discovering that one version of a plant — usually a random genetic mutant — was hardier, or sweeter, or had smaller seeds, would cross it with another that, say, produced more fruit, in hopes of getting both benefits. But the process was slow. Simply changing the color of a tomato from red to yellow while preserving its other traits could take years of crossbreeding. And tomatoes are one of the easiest cases. Introducing even a minor change to a cherry through crossbreeding, I was told, could take up to 150 years.To those who worry about G.M.O.s, that slowness is reassuring. “There’s a sense that, yes, these things have been altered,” Levinovitz noted. “But they’ve been altered over a very long time, in the same way that nature alters things.”Yet the way nature alters things is also profoundly haphazard. Sometimes a plant will acquire one trait at the expense of another. Sometimes it actually becomes worse. The same is true for agricultural crossbreeding. Not only is there no way to control which genes are kept and which are lost; the process also tends to introduce unwanted changes. The technical term for this is “linkage drag”: all the unintended, and unknown, genes that get pulled along during cross-pollination, like fish in a net. Commercial berry growers spent decades trying to create a domesticated version of the black raspberry through crossbreeding but never succeeded: the thornless berries either tasted worse or produced almost no fruit, or they developed other problems. It’s also why meeting the needs of modern agriculture — growing produce that can be shipped long distances and hold up in the store and at home for more than a few days — can result in tomatoes that taste like cardboard or strawberries that aren’t as sweet as they used to be. “With conventional breeding, you’re basically just shuffling the genetic deck,” the agricultural executive Tom Adams told me. “You’re never going to carry over only the gene you want.”In recent years genetic-engineering tools like CRISPR have offered a way around this imprecision, making it possible to identify which genes control which traits — things like color, hardiness, sweetness — and to change only those. “It’s far more precise,” says Andrew Allan, a plant biologist at the University of Auckland. “Instead of rolling the dice, you’re changing only the thing you want to change. And you can do it in one generation instead of 10 or 20.”Last year, the U.S.D.A. ruled that plants that had undergone simple cisgenic edits — changes to the plant’s own DNA, of the kind that could theoretically be created by years of traditional crossbreeding — would not be subject to the same regulation as other G.M.O.s. And some people are arguing that it’s time to reconsider how G.M.O.s are regulated as well, especially when it comes to small growers like Martin. From a regulatory perspective, Allan pointed out, all G.M.O.s are treated the same, regardless of the modification and regardless of the scale. “Whether you’re a corporation that wants to plant millions of acres of pest-resistant corn or someone who’s made a lovely little tomato that could save lives, it’s all the same process,” he said. Allan noted that his current project, the red flesh apple, contains a single gene taken from a crab apple which increases its antioxidants. “It’s an extremely low-risk change,” he said. “We’re literally just taking a gene from one kind of apple and putting it into another. But it is still, demonstrably, a G.M.O.”The policy is partly a holdover from the early days of genetic engineering, when less was known about the process and its effects. But it has persisted, in part because of powerful anti-G.M.O. campaigning. Eric Ward, co-chief executive of the agricultural technology company AgBiome, described the situation as “stuck in a closed loop.” He went on: “People think, Well, if you’ve got this really strict regulatory system, then it must be really dangerous. So it becomes self-reinforcing.”For Martin, this has created a strange catch-22. Grocery stores are afraid to carry something like a genetically modified tomato because they worry that consumers will reject it. Growers and businesses are afraid of investing in one for the same reason. Genetic engineering, Ward notes, has become far more accessible since the first G.M.O. crops were introduced in the 1990s. “But it’s turned into this thing that only half a dozen companies in the world can afford to do, because they’ve got to go through all this regulatory stuff.” He paused. “It’s ironic. The activists that first objected to G.M.O.s did it because they didn’t trust big agribusiness. But the result now is that only big companies can afford to do it.”Bobby Doherty for The New York TimesA few days before traveling to Norwich, I joined Martin at the Royal Society in London for the Future Food conference, a series of talks on genetic engineering in agriculture. There I met Haven Baker, a founder of a company called Pairwise, which was started to create fruits and vegetables that are genetically edited but not G.M.O.“I don’t think we can change people’s minds about G.M.O.s,” Baker said. “But gene editing is a clean slate. And maybe then G.M.O.s will be able to follow.”In his talk, Baker noted that there are hundreds of kinds of berries in the world. But among those we commonly call berries, we eat just four: strawberries, raspberries, blueberries and blackberries. There’s a reason the other varieties rarely reach us. Sometimes the fruit rots within days after picking (salmonberries), or the plant puts out fruit for only a few weeks in summer (cloudberries). Sometimes the plant doesn’t produce much fruit at all or is too thorny or sprawling for the fruit to be picked without a vast amount of labor. As Joel Reiner, a horticulturalist at Pairwise, would later put it, “Berries always have some tragic flaw.”Black raspberries, one fruit that Pairwise hopes to bring to market, used to be widely grown in North America, until a virus decimated them. (The red raspberries we eat now originally came from Turkey.) The revived version, which will be in field trials in 2024, has been engineered to be thornless and seedless, while retaining the fruit’s signature jammy flavor.More recently, the company began a similar project with vegetables. Baker says that we underestimate the mediocrity of most grocery-store produce, which tends to be tasteless and also offers little in the way of novelty. On top of that, most vegetables just aren’t very appealing, especially compared with processed foods. Vegetables take work to prepare, vary in quality and can be bitter or woody. They’re also perishable, often going bad before we get around to cooking them. “Especially if you’re on a budget, you hate the idea of wasting food,” Megan Thomas, one of Baker’s colleagues, noted. “You buy processed food, you can put it in the freezer or in the pantry for eight months and not worry about it.”These drawbacks have affected our diet. Only 10 percent of Americans eat the U.S. recommended daily allowance of fruit and vegetables, and teenagers eat even less. And that isn’t because the standard is particularly high: In an entire year, the average American consumes just a few heads of broccoli. “So how do we change that?” Baker asked. “People already know that they’re supposed to be eating vegetables. They just aren’t doing it. But if we can use gene editing to make broccoli slightly less bitter, maybe people — and especially kids — will eat more of it, and therefore be getting more fiber and more vitamins. Which might make a difference in their long-term health.”Not long after the conference, I flew to North Carolina to meet with Baker and his co-founder, Tom Adams. Before starting Pairwise, Baker and Adams each worked at large companies that invested in G.M.O. crops: Adams at Monsanto and Baker at Simplot, where he oversaw the development of a potato that produces less acrylamide, a carcinogen, when fried. (Monsanto, which is now owned by Bayer, provided some of the initial funding for Pairwise and retains the option to commercialize any innovation in row crops, though not in consumer produce.)Pairwise’s office is in an airy former textile mill that also houses a yoga studio, a tattoo parlor and several artist studios. When I showed up in February 2020, the area was just recovering from a winter storm that brought snow and black ice. Inside the greenhouses, though, it was warm and humid. “It’s a great place to work in the winter,” said Reiner, who tends to Pairwise’s plants. “In the summer it can get rough.”In anticipation of my visit, Reiner had set up samples from the company’s “superfood greens project,” which he described as creating “something that’s essentially lettuce but healthier.” Baker noted that Americans trying to eat well often order salads, but around half of those are made with iceberg or romaine lettuce, which have few nutrients and very little fiber. “If those empty leaves could be swapped for a healthy green, it would be a big nutrition boost,” he said. The problem is that nobody really likes the taste of healthy greens. “Do you want to guess what percent of the leafy green market is kale?” Baker asked at one point. “From what we can gather, it’s about 6 and a half percent. And the thing is, kale is known to be extremely good for you. It’s very rich in fiber and micronutrients: vitamins and minerals. But people don’t like to eat it.”In theory, gene editing could change that. Pairwise’s initial lettuce alternative, mustard greens, are in the same family as kale, Reiner explained, and have better nutritional value. But they’re extremely pungent, a trait the company hopes to minimize. For the tasting, Reiner laid out two varieties of genetically altered mustard greens. The first was beautiful: a dark green leaf veined with red, like a miniature chard. The edited version tasted extremely mild — perfect for salad — but when Reiner talked with consumer researchers, they complained that the leaves were too red. (“It’s OK to have a little bit of red, like some leaf lettuces,” Reiner explained. “But people expect most of what they see in the bag to be green.”)The second variety was more recognizable: a big, frilly, light green leaf that resembled the mustard greens I often buy — and then fail to eat — from the farmers’ market. That version was also extremely, almost inedibly, strong. Just nibbling the edge of a leaf cleared my sinuses like eating wasabi. “The compound that you’re tasting is called allyl isothiocyanate,” Reiner said as I dabbed at my watering eyes. “It’s not made until you chew it. The plant contains both the enzyme and the compound that converts it — but it holds them separate. When you chew, they combine to make something that tastes like horseradish. That’s why you have that little delay when you first bite into it, before it hits you.”By comparison, the genetically edited version was delightful, if almost unrecognizable: mild to the point of sweetness, with a pleasant, springy texture. It also has the advantage of looking more like romaine lettuce, and with its larger size and greater frilliness, it does a better job, as Reiner puts it, of “filling up the plate.” It seemed like something that I would happily eat, and in the months after the tasting, as I slogged through my usual salads, I found myself looking forward to the day when I could buy Pairwise’s mustard greens. I liked the idea of getting all that extra nutrition — the vitamins, the fiber — without the punishing pungency. But I also found myself worrying. If I got used to eating greens that were genetically edited to be milder, would I lose my tolerance for funkier ones, like bitter rapini or peppery radishes? At what point would I not want to eat even the local greens from the farmers’ market?After Baker’s talk at the Future Food conference, a member of the audience voiced the same concern: He was terrified, he said, by the prospect of using genetic engineering to “change what is natural just to meet people’s taste.” Rather than bending the natural world to our palates, shouldn’t we be adapting ourselves to the world? I put this question to Heather Hudson, who oversees Pairwise’s vegetable projects. Hudson smiled grimly. Modifying people’s taste, she said, is extremely difficult. An individual might manage it, by training her palate to appreciate, say, the slight bitterness of radicchio, but as a public health strategy it’s essentially hopeless. “I actually started out in nutrition, hoping to change how people ate,” Hudson went on. “But changing people’s behavior is hard.” There’s also a big difference between what we virtuously say we want and what we actually buy, let alone consume.This disconnect is something that Baker has thought about as well. With berries, Baker noted: “People definitely like them better when they’re sweeter. They don’t want sour berries, they want sweet berries!” From a purchasing perspective, he added, berries are in competition with “cheap sugar”: candies and cookies. “So, then you ask, should we even be editing these berries to make them sweeter? Have we then made these healthy berries more like candy?” He shook his head. “But the flip side is I don’t see us making progress on fruits and vegetables if we don’t make them more palatable at some level.”For all of Pairwise’s innovations, there’s a significant limit to how much a plant can be altered without making it a G.M.O. Insect-resistant crops like Bt corn and eggplant, for instance, rely on a gene from a bacterium; neither plant has a gene capable of performing the same function. Even Martin’s purple tomato would have been harder to make without using the transcription factor from snapdragons — although it would theoretically be possible. In general, it’s easy to stop an existing gene from functioning, but much harder to use gene editing to add a new trait or function.If Pairwise’s fruits and vegetables succeed with consumers, they will almost certainly open the door to other produce made through various kinds of genetic engineering. But getting shoppers to trust that these products are safe requires building confidence in how they’re regulated. “For a G.M.O., you’d want to ask: Is there anything in this which is toxic? Are there any novel proteins, or anything else potentially allergenic?” Lynas says. “And you’d do a compositional analysis. It’s basic food-safety stuff, really.” Gould and his co-authors on the National Academy of Sciences report have floated a more meticulous alternative: Researchers would compare the chemical and nutritional profiles of a genetically modified fruit or vegetable against existing varieties we’re already eating. “We have technologies now that allow you to check thousands of traits, to see if anything has changed,” Gould told me. “Why not use them to look at whether, you know, the vitamin C content in the orange you’ve made has gone down or stayed the same?”‘We’ve been changing all these things already with conventional breeding, and so far we’re doing all right. Making the same change with genetic engineering — there’s really no difference.’Should these sorts of comparisons become standard, they could determine, at a molecular level, whether there’s a measurable difference between the tomatoes and apples we’re already eating and the genetically modified version. Paradoxically, these comparisons might also reveal just how much ordinary breeding has already done to create the very changes we fear that G.M.O.s introduce: lowering a vegetable’s nutritional value, say, or increasing an allergen or invisibly altering the biochemical makeup of a plant in ways that could affect our long-term health. Conversely, they may show that G.M.O.s are just as safe, if not safer, than foods that have been altered more conventionally.Providing such safeguards for G.M.O. fruits and vegetables should be reassuring. But just as someone who distrusts vaccines tends to persist in that belief even when presented with abundant evidence of safety and efficacy, those who distrust G.M.O.s are unlikely to change their views until there’s a pressing reason. One possibly persuasive factor is climate change. As Allan notes, the global population is only increasing: By 2050, it will have gone up by two billion, and all those people need to be fed. “So where’s that extra food going to come from?” Allan says. “It can’t come from using more land, because if we use more land, then we’ve got to deforest more, and the temperature goes up even more. So what we really need is more productivity. And that, in all likelihood, will require G.M.O.s.”Others believe that we’ll embrace G.M.O.s only when the alternative is to lose something we value. For years, the Florida citrus industry has been plagued by “citrus greening,” a bacterial disease that is currently being controlled — with limited success — by sprayed antibiotics and pesticides. “If it comes down to buying orange juice that’s G.M.O., or not buying any orange juice, what are you going to choose?” the grower Harry Klee told me. “It’s the same thing that happened with the papaya in Hawaii. At some point, the consumer is going to have to decide what really matters to them.”One of those things might be the very biodiversity that G.M.O.s have helped diminish. As agriculture has industrialized, genetic diversity has shrunk profoundly, with monocultures (or a limited number of hardy varieties) replacing what was once a cornucopia of wild varieties. One study found that before G.M.O.s were even introduced, we’d lost 93 percent of the genetic diversity in our fruits and vegetables. In the early 1900s, farmers in Iowa regularly grew pink-fleshed Chelsea watermelons, which were known for being intensely sweet but have now all but disappeared because they’re too delicate for shipping. Blenheim apricots, once widely cultivated in California, have a sublime, honeyed flavor and a delicate blush-mottled skin, but also bruise easily and ripen from the inside out, confusing consumers. As a result, fresh Blenheims are now almost impossible to find, even though, as the food writer Russ Parsons put it, they’re the apricot that “reminds you of what that fruit is supposed to taste like.”Genetic engineering and G.M.O.s could help undo these losses, restoring rare and delicate heirloom varieties that were once abundant but have now all but disappeared. One appealing vision is for small growers and academics to figure out what tiny modification would make Blenheims slightly more durable, while preserving everything else about the texture and flavor. While the apricot will most likely never be hardy or controllable enough for mass production, it might be made sturdy enough to allow small producers to plant an orchard that’s sustainable.It’s not just the most fragile fruits that we’re losing — or may soon lose. Cherries, for instance, are highly sensitive to rain and frost, a problem that makes them especially vulnerable to climate change. They’re also extremely seasonal, ripening all at once over the span of just a few weeks, rather than growing year-round. Faced with labor shortages and shrinking profits, some growers have begun talking about converting their cherry orchards to apples, which keep better and are less risky. To prevent that from happening, Hudson suggested that cherries could be made easier to pick, and perhaps grown year-round, like blueberries (which until recently were also highly seasonal). “Doing that means the farmer gets stability, and the workers get stability,” she added.But we’re unlikely to see these kinds of projects while G.M.O.s remain the exclusive product of global agrochemical companies. While a researcher at an agricultural college might be interested in bringing back the Blenheim — or creating a wonderful new antioxidant tomato — the financial payoff is nonexistent. “Imagine you’re a big company,” says Ward, the AgBiome chief executive. “You can put a dollar into an insect-control trait in soybean and bring in 10 to 15 billion dollars. Or you can put a dollar into a healthier tomato that at peak might be worth a few million dollars. It’s pretty simple financial calculation.”There are some signs that the future of small-scale, bespoke G.M.O. produce may already have begun. In late April, Cathie Martin told me that the U.S.D.A. had recently updated its regulations to allow more G.M.O. plants to be grown outside, without a three-year field trial or in tightly contained greenhouses. (The exceptions are plants or organisms with the potential to be a pest, pathogen or weed.) In the wake of this change, Martin and Jones are planning to make the purple tomato available first to home gardeners, who could grow it from seed as soon as next spring — well before the commercially grown tomato reaches grocery stores. (U.S.D.A. approval is expected by December.) They’re currently testing six different varieties, to find the most flavorful. “When we first developed the purple tomato, it was home gardeners who were most interested in it,” Martin noted. “And with home gardening, it’s an opt-in system. It’s up to you whether you want to grow it.”It was an intriguing idea. Months earlier, while browsing a website called The Garden Professors, I noticed that a home gardener named Janet Chennault had posted a query asking where she could buy G.M.O. seeds. Others had wondered the same thing. “I would love to try some G.M. vegetable seeds in my garden,” a woman named Lorrie Delehanty said.After some searching, I managed to track down Delehanty, who had recently retired and was living in Charlottesville, Va. Over the phone, she described herself as having “a little tiny backyard in the middle of the city” that she and her husband had worked hard to homestead, planting blackberries along the fence line and creating a bird sanctuary around the vegetable plot. She was interested in G.M. seeds, she said, because she did her own canning and freezing, “and I’m always looking to grow something different.”When I asked what kind of thing she was looking for, Delehanty grew animated. “Something with the sweet, smoky flavor of a scorpion pepper without the screaming heat,” she began. “Also potatoes that resist bacterial scab. I’m sick and tired of getting scabby potatoes. The purple tomato — I would try that in a heartbeat.” She paused. “Oh, and bigger blackberries!”Jennifer Kahn is a contributing writer for the magazine and the narrative-program lead at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. Levon Biss is a British photographer known for his extremely magnified images of natural subjects like insects and seeds. Bobby Doherty is a photographer based in Brooklyn who focuses on studio still-life photography. His first book, “Seabird,” is a collection of moments observed from 2014 to 2018.

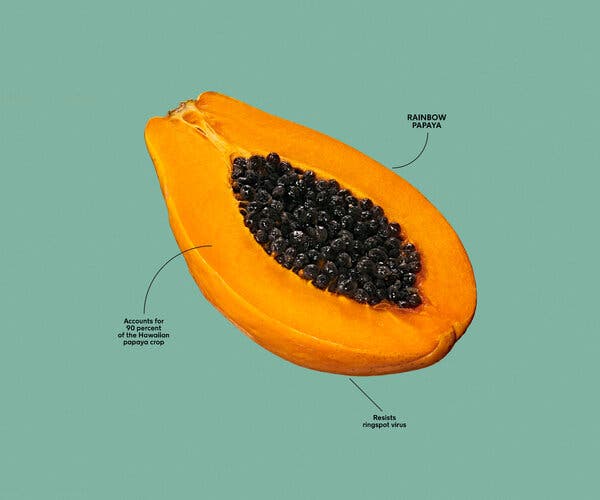

Read more →