It was March 1827 and Ludwig van Beethoven was dying. As he lay in bed, wracked with abdominal pain and jaundiced, grieving friends and acquaintances came to visit. And some asked a favor: Could they clip a lock of his hair for remembrance?The parade of mourners continued after Beethoven’s death at age 56, even after doctors performed a gruesome craniotomy, looking at the folds in Beethoven’s brain and removing his ear bones in a vain attempt to understand why the revered composer lost his hearing.Within three days of Beethoven’s death, not a single strand of hair was left on his head.Ever since, a cottage industry has aimed to understand Beethoven’s illnesses and the cause of his death.Now, an analysis of strands of his hair has upended long held beliefs about his health. The report provides an explanation for his debilitating ailments and even his death, while also raising new questions about his genealogical origins and hinting at a dark family secret.The paper, by an international group of researchers, was published Wednesday in the journal Current Biology.It offers additional surprises: A famous lock of hair — the subject of a book and a documentary — was not Beethoven’s. It was from an Ashkenazi Jewish woman.The study also found that Beethoven did not have lead poisoning, as had been widely believed. Nor was he a Black man, as some had proposed.And a Flemish family in Belgium — who share the last name van Beethoven and had proudly claimed to be related — have no genetic ties to him.Researchers not associated with the study found it convincing.It was “a very serious and well-executed study, “ said Andaine Seguin-Orlando, an expert in ancient DNA at the University Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, in France.The detective work to solve the mysteries of Beethoven’s illness began on Dec. 1, 1994, when a lock of hair said to be Beethoven’s was auctioned by Sotheby’s. Four members of the American Beethoven Society, a private group that collects and preserves material related to the composer, purchased it for $7,300. They proudly displayed it at the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies at San Jose State University in California.But was it really Beethoven’s hair?The Hiller lock, which the study found did not come from Beethoven but a woman, with its inscription by its former owner, Paul Hiller.William Meredith/Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San Jose State UniversityThe story was that it was clipped by Ferdinand Hiller, a 15-year-old composer and ardent acolyte who visited Beethoven four times before he died.On the day Beethoven died, Hiller clipped a lock of his hair. He gave it to his son decades later as a birthday gift. It was kept in a locket.The locket with its strands of hair was the subject of a best-selling book, “Beethoven’s Hair,” by Russell Martin, published in 2000, and made into a documentary film in 2005.An analysis of the hair at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois found lead levels as high as 100 times normal.In 2007, authors of a paper in The Beethoven Journal, a scholarly journal published by San Jose State, speculated that the composer might have been inadvertently poisoned by medicine, wine, or eating and drinking utensils.That was where matters stood until 2014 when Tristan Begg, then a masters student studying archaeology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, realized that science had advanced enough for DNA analysis using locks of Beethoven’s hair.“It seemed worth a shot,” said Mr. Begg, now a Ph.D. student at Cambridge University.William Meredith, a Beethoven scholar, began searching for other locks of Beethoven’s hair, buying them with financial support from the American Beethoven Society, at private sales and auctions. He borrowed two more from a university and a museum. He ended up with eight locks, including the hairs from Ferdinand Hiller.First, the researchers tested the Hiller lock. Because it turned out to be from a woman, it was not — could not be — Beethoven’s. The analysis also showed that the woman had genes found in Ashkenazi Jewish populations.Dr. Meredith speculates that the authentic hair from Beethoven was destroyed and replaced with strands from Sophie Lion, the wife of Ferdinand Hiller’s son Paul. She was Jewish.Lab work on the Moscheles lock at the University of Tübingen in Germany.Susanna SabinAs for the other seven locks, two were inauthentic, four had identical DNA and one could not be tested. The four locks with identical DNA were of different provenances and two had impeccable chains of custody, which gave the researchers confidence that they were hair from Beethoven.Ed Green, an expert in ancient DNA at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved with the study, agreed.“The fact that they have so many independent locks of hair, with different histories, that all match one another is compelling evidence that this is bona fide DNA from Beethoven,” he said.When the group had the DNA sequence from Beethoven’s hair, they tried to answer longstanding questions about his health. For instance, why might he have died from cirrhosis of the liver?He drank, but not to excess, said Theodore Albrecht, a professor emeritus of musicology at Kent State University in Ohio. Based on his study of texts left by the composer, he described what is known of Beethoven’s imbibing habits in an email.“In none of these activities did Beethoven exceed the line of consumption that would make him an ‘alcoholic,’ as we would commonly define it today,” he wrote.Beethoven’s hair provided a clue: He had DNA variants that made him genetically predisposed to liver disease. In addition, his hair contained traces of hepatitis B DNA, indicating an infection with this virus, which can destroy a person’s liver.But how did Beethoven get infected? Hepatitis B is spread through sex and shared needles, and during childbirth.Beethoven did not use intravenous drugs, Dr. Meredith said. He never married, although he was romantically interested in several women. He also wrote a letter — although he never sent it — to his “immortal Beloved,” whose identity has been the subject of much scholarly intrigue. Details of his sex life remain unknown.The Stumpff lock, from which Beethoven’s whole genome was sequenced, with an inscription by its former owner Patrick Stirling.Kevin BrownArthur Kocher, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany and one of the new study’s co-authors, offered another possible explanation for his infection: The composer could have been infected with hepatitis B during childbirth. The virus is commonly spread this way, he said, and infected babies can end up with a chronic infection that lasts a lifetime. In about a quarter of people, the infection will eventually lead to cirrhosis of the liver or liver cancer.“It could ultimately lead someone to die of liver failure,” he said.The study also revealed that Beethoven was not genetically related to others in his family line. His Y chromosome DNA differed from that of a group of five people with the same last name — van Beethoven — living in Belgium today and who, according to archival records, share a 16th-century ancestor with the composer. That indicates there must have been an out-of-wedlock affair in Beethoven’s direct paternal line. But where?Maarten Larmuseau, a co-author of the new study who is a professor of genetic genealogy at the University of Leuven in Belgium, suspects that Ludwig van Beethoven’s father was born to the composer’s grandmother with a man other than his grandfather. There are no baptismal records for Beethoven’s father, and his grandmother was known to have been an alcoholic. Beethoven’s grandfather and father had a difficult relationship. These factors, Dr. Lamarseau said, are possible signs of an extramarital child.Beethoven had his own difficulties with his father, Dr. Meredith said. And while his grandfather, a noted court musician in his day, died when Beethoven was very young, he honored him and kept his portrait with him until the day he died.Dr. Meredith added that when rumors circulated that Beethoven was actually the illegitimate son of Friedrich Wilhelm II or even Frederick the Great, Beethoven never refuted them.The researchers had hoped their study of Beethoven’s hair might explain some of the composer’s agonizing health problems. But it did not provide definitive answers.The composer suffered from terrible digestive problems, with abdominal pain and prolonged bouts of diarrhea. The DNA analysis did not point to a cause, although it pretty much ruled out two proposed reasons: celiac disease and ulcerative colitis. And it made a third hypothesis — irritable bowel syndrome — unlikely.Hepatitis B could have been the culprit, Dr. Kocher said, although it is impossible to know for sure.The DNA analysis also offered no explanation for Beethoven’s hearing loss, which started in his mid-20s and resulted in deafness in the last decade of his life.An 1827 lithograph of Beethoven on his deathbed by Josef Danhauser, after his own drawing.Josef Danhauser, via Beethoven-Haus BonnThe researchers took pains to discuss their results in advance with those directly affected by their research.On the evening of March 15, Dr. Larmuseau met with the five people in Belgium whose last name is van Beethoven and who provided DNA for the study.He started right out with the bad news: They are not genetically related to Ludwig van Beethoven.They were shocked.“They didn’t know how to react,” Dr. Larmuseau said. “Every day they are remembered by their special surname. Every day they say their name and people say, ‘Are you related to Ludwig van Beethoven?’”That relationship, Dr. Larmuseau said, “is part of their identity.”And now it is gone.The study’s findings that the Hiller lock was from a Jewish woman stunned Mr. Martin, author of “Beethoven’s Hair.”“Wow, who would have imagined it,” he said. Now, he added, he wants to find descendants of Sophie Lion, the wife of Paul Hiller, to see if the hair was hers. And he’d like to find out if she had lead poisoning.For Dr. Merrill, the project has been an amazing adventure.“The whole complex story is astonishing to me.” he said. “And I’ve been part of it since 1994. One finding just leads to another unexpected finding.”

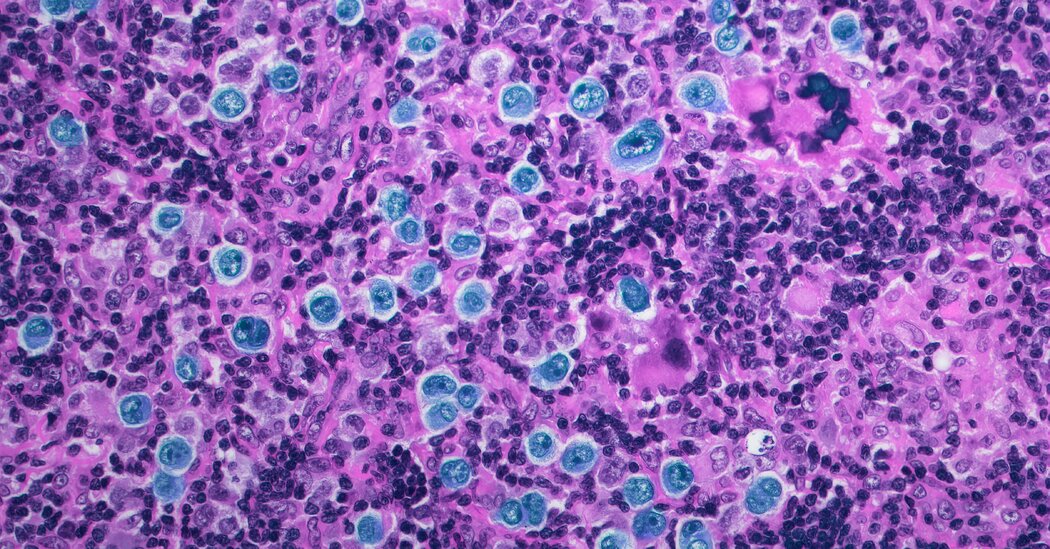

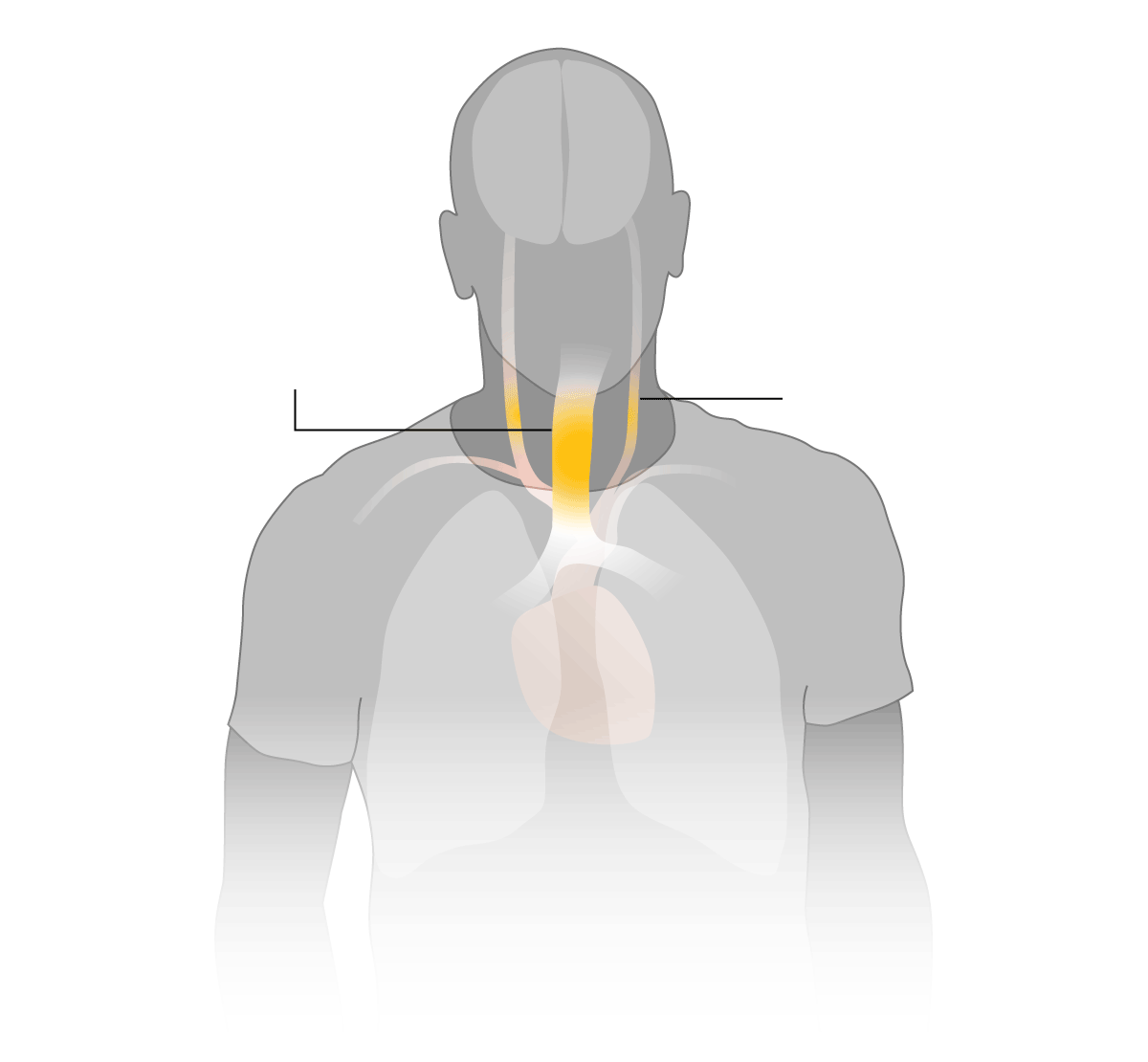

Read more →