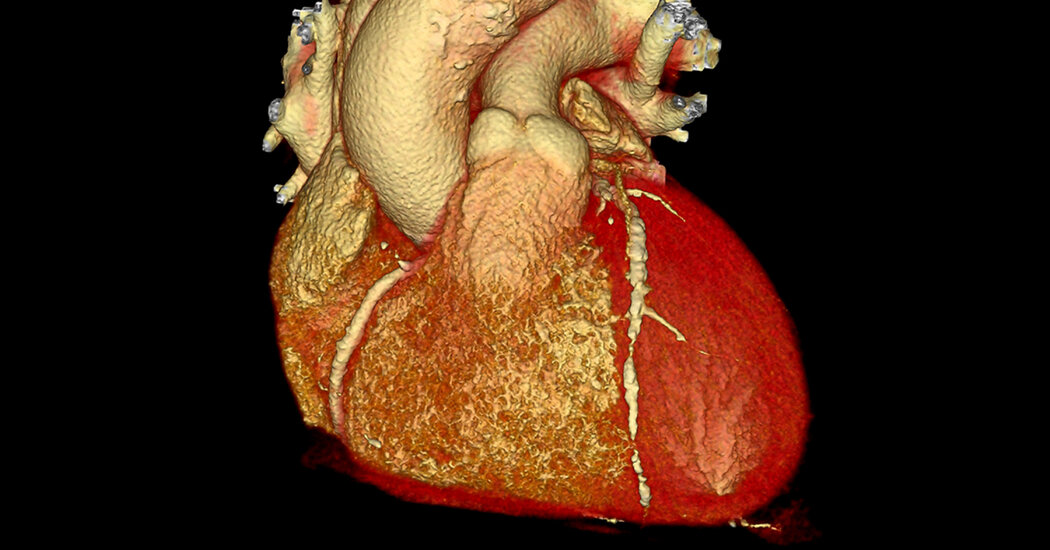

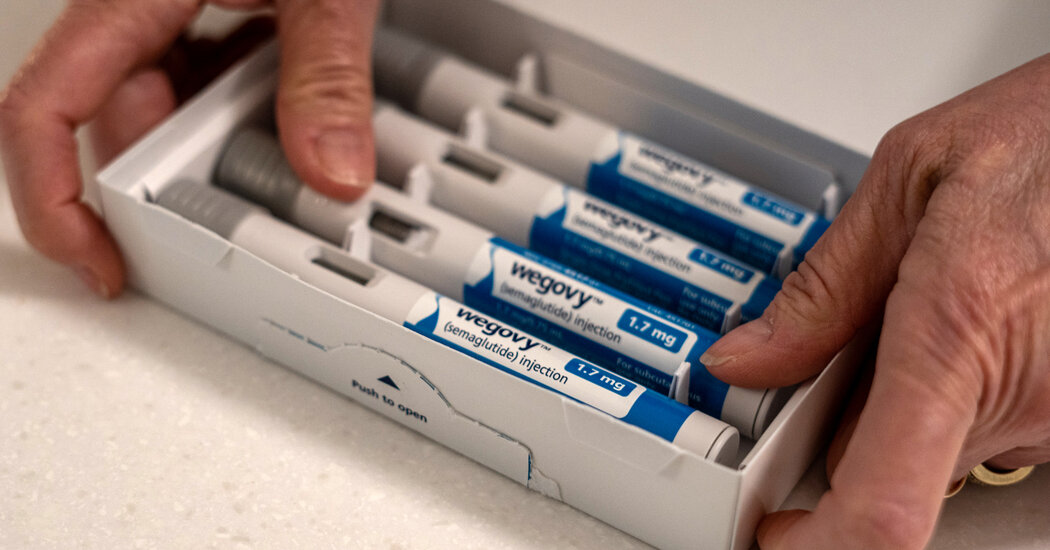

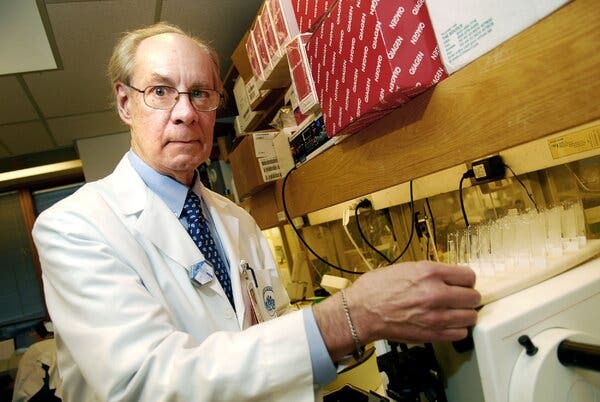

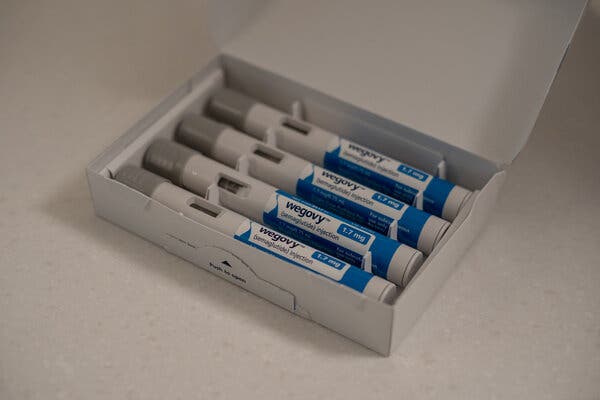

Every so often a drug comes along that has the potential to change the world. Medical specialists say the latest to offer that possibility are the new drugs that treat obesity — Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro and more that may soon be coming onto the market.It’s early, but nothing like these drugs has existed before.“Game changers,” said Jonathan Engel, a historian of medicine and health care policy at Baruch College in New York.Obesity affects nearly 42 percent of American adults, and yet, Dr. Engel said, “we have been powerless.” Research into potential medical treatments for the condition led to failures. Drug companies lost interest, with many executives thinking — like most doctors and members of the public — that obesity was a moral failing and not a chronic disease.While other drugs discovered in recent decades for diseases like cancer, heart disease and Alzheimer’s were found through a logical process that led to clear targets for drug designers, the path that led to the obesity drugs was not like that. In fact, much about the drugs remains shrouded in mystery. Researchers discovered by accident that exposing the brain to a natural hormone at levels never seen in nature elicited weight loss. They really don’t know why.“Everyone would like to say there must be some logical explanation or order in this that would allow predictions about what will work,” said Dr. David D’Alessio, chief of endocrinology at Duke, who consults for Eli Lilly among others. “So far there is not.”Although the drugs seem safe, obesity medicine specialists call for caution because — like drugs for high cholesterol levels or high blood pressure — the obesity drugs must be taken indefinitely or patients will regain the weight they lost.Dr. Susan Yanovski, a co-director of the office of obesity research at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, warned that patients would have to be monitored for rare but serious side effects, especially as scientists still don’t know why the drugs work.But, she added, obesity itself is associated with a long list of grave medical problems, including diabetes, liver disease, heart disease, cancers, sleep apnea and joint pain.“You have to keep in mind the serious diseases and increased mortality that people with obesity suffer from,” she said.The drugs can cause transient nausea and diarrhea in some. But their main effect is what matters. Patients say they lose constant cravings for food. They find themselves satisfied with much smaller portions. They lose weight because they naturally eat less — not because they burn more calories.And results from a clinical trial reported last week indicate that Wegovy can do more than help people lose weight — it also can protect against cardiac complications, like heart attacks and strokes.But why that happens remains poorly understood.“Companies don’t like the term trial and error,” said Dr. Daniel Drucker, who studies diabetes and obesity at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto and who consults for Novo Nordisk and other companies. “They like to say, ‘We were extremely clever in the way we designed the molecule,” Dr. Drucker said.But, he said, “They did get lucky.”A Lonely Origin StoryDr. Joel Habener in 2007.Ruby Arguilla-Tull/Bloomberg NewsIn the 1970s, obesity treatments were the last thing on Dr. Joel Habener’s mind. He was an academic endocrinologist starting his own lab at Harvard Medical School and looking for a challenging, but doable, research project.He chose diabetes. The disease is caused by high blood sugar levels and is typically treated with injections of insulin, a hormone secreted by the pancreas that helps cells store sugar. But an insulin injection makes blood sugar plummet, even if levels are already low. Patients have to carefully plan injections because very low blood sugar levels can result in confusion, shakiness and even a loss of consciousness.Two other hormones also play a role in regulating blood sugar — somatostatin and glucagon — and little was known then about how they are produced. Dr. Habener decided to study the genes that direct cells to make glucagon.That led him to a real surprise. In the early 1980s, he discovered a hormone, GLP-1, that exquisitely regulates blood sugar. It acts only on insulin-producing cells of the pancreas, and only when blood sugar rises too high.It was perfect, in theory, as a targeted treatment to replace sledgehammer-like insulin injections.Another researcher, Dr. Jens Juul Holst at the University of Copenhagen, independently stumbled on the same discovery.But there was a problem: When GLP-1 was injected, it vanished before reaching the pancreas. It needed to last longer.Dr. Drucker, who led the GLP-1 discovery efforts on Dr. Habener’s team, labored for years on the challenge. It was, he said, “a pretty lonely field.”When he applied to the Endocrine Society to give talks, he found himself scheduled at the very end of the last day of the annual meetings.“Everyone had left for the airport — people were taking down the exhibits,” he said.From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, he spoke to nearly empty auditoriums.Dr. Eng’s MonsterPeter DaSilva for The New York TimesSuccess came from a chance discovery that was not appreciated at the time.In 1990, John Eng, a researcher at the Veterans Affairs medical center in the Bronx, was looking for interesting new hormones in nature that might be useful for medications in people.He was drawn to the venomous Gila monster when he learned that it somehow kept its blood sugar levels stable when it did not have much to eat, according to a report from the National Institutes of Health, which funded his work. So Dr. Eng decided to search for chemicals in the lizards’ saliva. He found a variant of GLP-1 that lasted longer.Dr. Eng told The New York Times in 2002 that the V.A. had declined to patent the hormone. So Dr. Eng patented it himself and licensed it to Amylin Pharmaceuticals, which began testing it as a diabetes drug. The drug, exenatide or Byetta, went on sale in the United States in 2005.But Byetta had to be injected twice a day, a real disincentive to its use. Drug company chemists sought even longer-lasting versions of GLP-1.At Novo Nordisk, chemists began by using a well-known trick. They loosely attached GLP-1 to a blood protein that kept it stable enough to remain in circulation for at least 24 hours. But when GLP-1 slips off the protein, enzymes in the blood quickly degrade it. So chemists had to alter the hormone’s building blocks — a chain of amino acids — to find a more durable variant.After tedious trial and error, Novo Nordisk produced liraglutide, a GLP-1 drug that lasted long enough for daily injections. They named it Saxenda, and the F.D.A. approved it as a treatment for diabetes in 2010.It had an unexpected side effect: slight weight loss.A Dismal HistoryDr. Jeffrey Friedman, who discovered the hormone that tells the brain how much fat is on the body, in 1995.Remi Benali/Gamma-Rapho, via Getty ImagesObesity had become a dead end in the pharmaceutical industry. No drug that was tried worked very well, and every one that led to even modest weight loss had serious side effects.For a flickering moment in the late 1990s, there was hope when Dr. Jeffrey Friedman at Rockefeller University in New York found a hormone that told the brain how much fat was on the body. Lab mice genetically modified to have none of the hormone ate voraciously and grew enormously fat. Researchers could fine-tune an animal’s weight by altering how much of the hormone it got.Dr. Friedman named the hormone leptin. Amgen bought the rights to leptin and, in 1996, began testing it in people. They did not lose weight.Dr. Matthias Tschöp at Helmholtz Munich in Germany tells of the frustration. He left academia three decades ago to work at Eli Lilly in Indianapolis, excited by leptin and determined to use science to find a drug for weight loss.“I was so inspired,” Dr. Tschöp said.When leptin failed, he tried a different gut hormone, ghrelin, whose effects were the opposite of leptin’s. The more ghrelin an animal had, the more it would eat. Perhaps a drug that blocked ghrelin would make people lose weight.“Again, it wasn’t that simple,” said Dr. Tschöp, who left Lilly in 2002.The body has so many redundant circuits of interacting nerve impulses and hormones to control weight that tweaking one simply did not make a difference.And there was another obstacle, noted Dr. Tschöp’s former colleague at Lilly, Dr. Richard Di Marchi, who also was an executive at Novo Nordisk.“There was very little interest in the industry in doing this,” said Dr. Di Marchi, now at Indiana University. “Obesity was not thought to be a disease. It was looked at as a behavioral problem.”Dr. Friedman studied mice that had been genetically modified to have none of a hormone that told their brains how much fat was on their bodies. Researchers could fine-tune an animal’s weight by altering its hormones, but the study failed in humans.Remi Benali/Gamma-Rapho, via Getty ImagesStarving RatsNovo Nordisk, which today has 45.7 percent of the global insulin market, thought of itself as a diabetes company. Period.But one company scientist, Lotte Bjerre Knudsen, could not stop thinking about tantalizing results from studies with liraglutide, the GLP-1 drug that lasted long enough to be injected just once a day.In the early 1990s, Novo researchers, studying rats implanted with tumors of pancreas cells that produced copious amounts of glucagon and GLP-1, noticed that the animals had nearly stopped eating.“These rats, they starved themselves,” Dr. Knudsen said in a video series released by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. “So we kind of knew there was something in some of these peptides that was really important for appetite regulation.”Other studies by academic researchers found that rats lost their appetites if GLP-1 was injected into their brains. Human subjects who got an intravenous drip of GLP-1 ate 12 percent less at a lunch buffet than those who got a placebo.So why not study liraglutide as both a diabetes drug and an obesity drug, Dr. Knudsen asked .She faced resistance in part because some company executives were convinced that obesity resulted from a lack of willpower. One of the champions of investigating GLP-1 for weight loss, Lars Rebien Sorensen, chairman of the board at Novo Nordisk, said in the video posted by the company’s foundation that he “had to spend half a year convincing my C.E.O. that obesity is not just a lifestyle condition.”Dr. Knudsen also noted that the company’s business division had struggled with the idea of promoting liraglutide for two distinct purposes.“It’s either diabetes, or it’s a weight loss,” she recalled in the foundation video series.Finally, after liraglutide was approved in 2010 for diabetes, Dr. Knudsen’s proposal to study the drug for weight loss moved forward. After clinical trials, the F.D.A. approved liraglutide, or Saxenda, for obesity in 2014. The dose was about twice the diabetes dose. Patients lost about 5 percent of their weight, a modest amount.But Dr. Martin Holst Lange, executive vice president of development at Novo Nordisk, said in a telephone interview that it was at least as good as other weight-loss drugs, and without side effects like heart attacks, strokes and death.“We were super excited,” he said.Beyond DiabetesA Novo Nordisk site outside Copenhagen.Scanpix Denmark/ReutersDespite the progress on weight loss, Novo Nordisk continued to focus on diabetes, trying to find ways to make a longer-lasting GLP-1 so patients would not have to inject themselves every day.The result was a different GLP-1 drug, semaglutide, that lasted long enough that patients had to inject themselves only once a week. It was approved in 2017 and is now marketed as Ozempic.It also caused weight loss — 15 percent, which is three times the loss with Saxenda, the once-a-day drug, although there was no obvious reason for that. Suddenly, the company had what looked like a revolutionary treatment for obesity.But Novo Nordisk could not market Ozempic for weight loss without F.D.A. approval for that specific use.In 2018, a year after Ozempic’s approval for diabetes, the company started a clinical trial. In 2021, Novo Nordisk got approval from the F.D.A. to market the same drug for obesity with a weekly injection at a higher maximum dose. It named the drug Wegovy.But even before Wegovy was approved, people had begun taking Ozempic for obesity. Novo Nordisk, in its Ozempic commercials, mentioned that many taking it lost weight.Hinting turned out to be more than enough. Soon, said Dr. Jeffrey Mechanick, an endocrinologist at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine, patients latched onto Ozempic. Doctors prescribed it off label for those who did not have diabetes.“There was a little bit of gaming going on,” Dr. Mechanick said, with some doctors coding patients as having pre-diabetes to help them get insurance coverage.By 2021, fed by social media, a general frenzy for weight loss and aggressive marketing by Novo Nordisk, the news that Ozempic made people lose weight had reached a tipping point, said Dr. Caroline Apovian, a co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a consultant for Novo Nordisk and other companies. Ozempic was on everyone’s lips, even though Wegovy was the drug approved that year for obesity.But Wegovy caught up.In July, doctors in the U.S. wrote about 94,000 prescriptions a week for Wegovy compared with about 62,000 a week for Ozempic. Wegovy is in such demand, though, that the company is unable to make enough, its spokeswoman Ambre James-Brown said. So for now, while it ramps up production, the company sells the drug only in Norway, Denmark, Germany and the United States. And at pharmacies in those countries, shortages are frequent.And Dr. Apovian, like many other obesity medicine specialists, is now booked with patients a year in advance.Cydni Elledge for The New York TimesMore Medicines, More MysteriesThe reason Ozempic and Wegovy are so much more effective than Saxenda remains a mystery. Why should a once-a-week injection produce much more weight loss than a once-a-day injection?The drugs, said Randy Seeley, an obesity researcher at the University of Michigan, are not correcting for a lack of GLP-1 in the body — people with obesity make plenty of GLP-1. Instead, the drugs are exposing the brain to hormone levels never seen in nature. Patients taking Wegovy are getting five times the amount of GLP-1 that they would produce in response to a Thanksgiving dinner, Dr. Seeley said.And, he added, in the brain, “the drugs go to unusual places.” They are not just going to areas thought to involve control overeating.“If you were designing a drug, you would say that’s a bad idea,” said Dr. Seeley, who has consulted for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, among others. Drug designers try for precision — a drug should go only to the cells where it is needed.GLP-1, because of its chemical structure, should not even get into some areas of the brain where it slips in.“Nobody understands that,” Dr. Seeley said.Wegovy, though, is just the start.Lilly’s diabetes drug, tirzepatide or Mounjaro, is expected to get F.D.A. approval for obesity this year. It hooks GLP-1 to another gut hormone, GIP.GIP, on its own, produces, at best, a modest weight loss. But the two-hormone combination can allow people to lose a median of about 20 percent of their weight.“No one fully understands why,” Dr. Drucker said.Lilly has another drug, retatrutide, that, while still in early stages of testing, seems to elicit a median 24 percent weight loss.Amgen’s experimental drug, AMG 133, could be even better, but is even more of a puzzle. It hooks GLP-1 to a molecule that blocks GIP.There is no logical explanation for why seemingly opposite approaches would work.Researchers continue to marvel at these biochemical mysteries. But doctors and patients have their own takeaway: The drugs work. People lose weight. The constant chatter in their brains about food and eating is gone.And, while the stigma of obesity and the cultural stereotype that obese people aren’t trying hard enough to lose weight endures, some experts are optimistic. Now, they say, patients no longer have to blame themselves or feel like failures when they can’t lose weight.“The era of ‘just go out and diet and exercise’ is now gone,’” said Dr. Rudolph Leibel, a professor of diabetes research at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “Now clinicians have tools to address obesity.”

Read more →