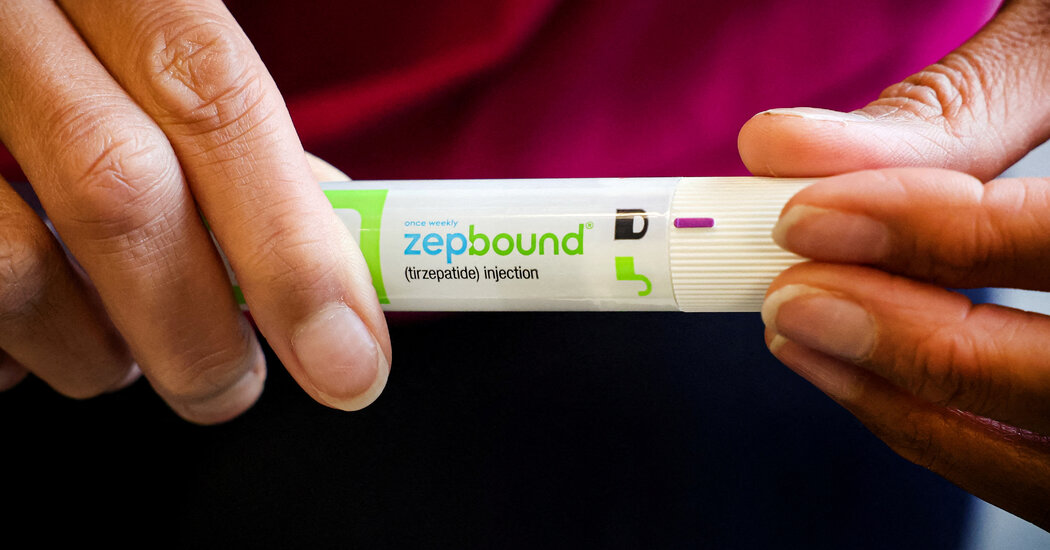

Sleep Apnea Reduced in People Who Took Zepbound, Eli Lilly Reports

The company reported results of clinical trials involving Zepbound, an obesity drug in the same class as Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy.The pharmaceutical manufacturer Eli Lilly announced on Wednesday that its obesity drug tirzepatide, or Zepbound, provided considerable relief to overweight or obese people who had obstructive sleep apnea, or episodes of stopped breathing during sleep.The results, from a pair of yearlong clinical trials, could offer a new treatment option for some 20 million Americans who have been diagnosed with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea. Most people with the condition do not realize they have it, according to the drug manufacturer. People with sleep apnea struggle to get enough sleep, and they face an increased risk for high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, strokes and dementia.The study’s findings have not been published in a peer-reviewed medical journal. Eli Lilly provided only a summary of its results — companies are required to announce such findings that can affect their stock price as soon as they get them. Dr. Daniel M. Skovronsky, Eli Lilly’s chief scientific officer, said the company was still analyzing the data and would provide detailed results at the American Diabetes Association’s 84th Scientific Sessions in June.But experts not affiliated with Eli Lilly or involved in its studies were encouraged by the summary.“That’s awesome,” said Dr. Henry Klar Yaggi, director of the Yale Centers for Sleep Medicine in New Haven, Conn.He added that the most common treatment, a CPAP machine that forces air into the airway, keeping it open during sleep, is effective. About 60 percent of patients who use continuous positive airway pressure continue to use it, he said.We are having trouble retrieving the article content.Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.Thank you for your patience while we verify access.Already a subscriber? Log in.Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Read more →