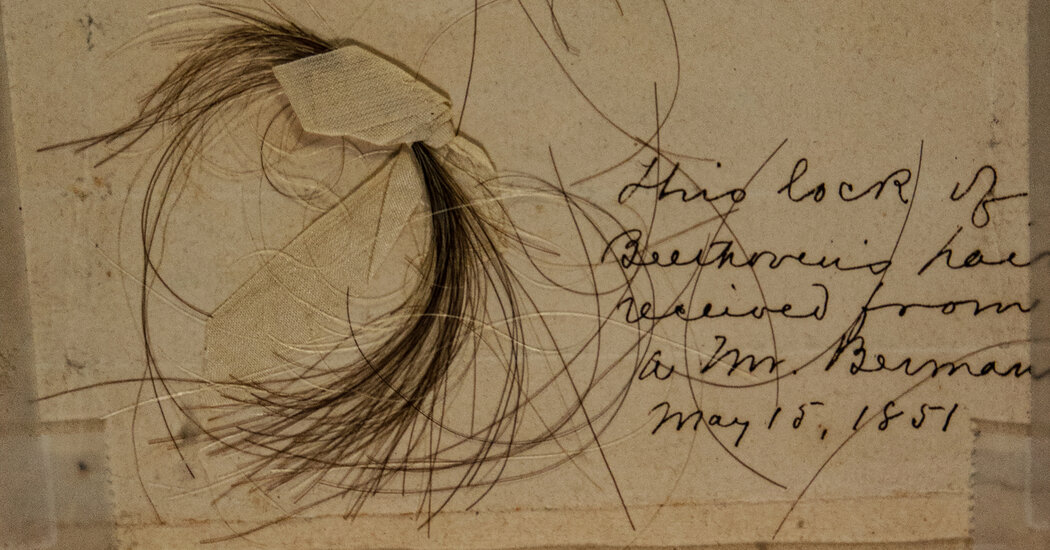

Lead in Beethoven’s Hair Offers New Clues to Mystery of His Deafness

Using powerful technologies, scientists found staggering amounts of lead and other toxic substances in the composer’s hair that may have come from wine, or other sources.At 7 p.m. on May 7, 1824, Ludwig van Beethoven, then 53, strode onto the stage of the magnificent Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna to help conduct the world premiere of his Ninth Symphony, the last he would ever complete.That performance, whose 200th anniversary is on Tuesday, was unforgettable in many ways. But it was marked by an incident at the start of the second movement that revealed to the audience of about 1,800 people how deaf the revered composer had become.Ted Albrecht, a professor emeritus of musicology at Kent State University in Ohio and author of a recent book on the Ninth Symphony, described the scene.The movement began with loud kettledrums, and the crowd cheered wildly.But Beethoven was oblivious to the applause and his music. He stood with his back to the audience, beating time. At that moment, a soloist grasped his sleeve and turned him around to see the raucous adulation he could not hear.It was one more humiliation for a composer who had been mortified by his deafness since he had begun to lose his hearing in his twenties.But why had he gone deaf? And why was he plagued by unrelenting abdominal cramps, flatulence and diarrhea?We are having trouble retrieving the article content.Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.Thank you for your patience while we verify access.Already a subscriber? Log in.Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Read more →