I’m Haunted by Sisters With Sickle Cell: Two Thrived. Two Suffered.

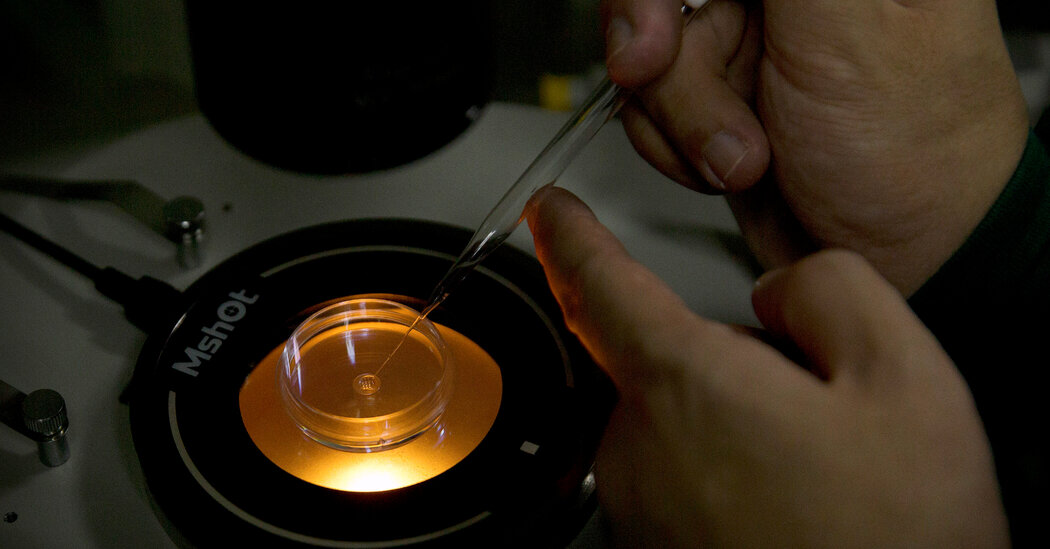

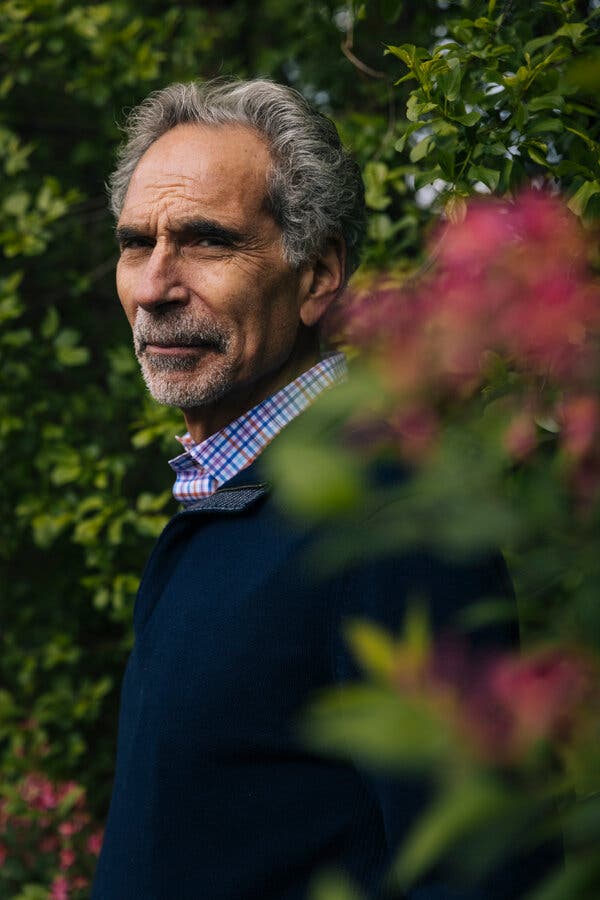

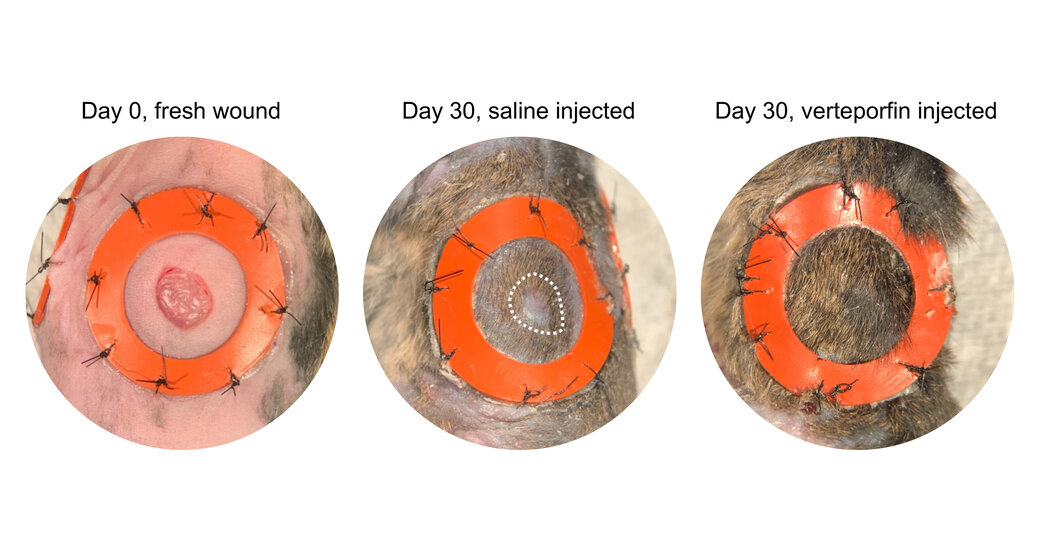

The cruelty of their unequal outcomes — with one pair freed of disabling symptoms and the other’s suffering unabated — stayed with me.Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.As a medical reporter, I regularly write about terrible illnesses and about treatments that can help some, though not most, patients. But the cruel injustice of inequities in access to medical advances in sickle cell disease took my breath away.I didn’t plan it this way, but I ended up writing about two families who, at the start, were strikingly similar. Each had two teenage daughters with sickle cell disease. All four girls suffered episodes of intense pain, damage to organs and bones, and life-threatening lung complications. And one pair of the sisters had strokes.But in one family, both girls were freed from their symptoms and are now living normal lives. In the other, the sisters are still suffering and yearning for the chance to rid themselves of the disease.I followed one of the families for two years and the other for over a year, and I am haunted by the disparities.Helen Obando at the hospital the day she got the good news that her gene therapy was working. Two years later, she is rid of her symptoms of sickle cell.Hilary Swift for The New York TimesThe tale of these two families reveals in a microcosm the state of the science for this terrible disease. Sickle cell is caused by a single mutation in a globin gene needed to make red blood cells. The cells turn sickle shaped and can get stuck in blood vessels, injuring them and impeding blood flow. An estimated 100,000 Americans have the disease — most of them Black and many of modest means. Although the cause of the disease has been known for more than half a century, research has been slow and underfunded. Even discoveries that could improve patients’ lives are often not used.There is a bone-marrow transplant that gives the patient the blood system of a healthy person. But it is rarely used because few sickle cell patients have a donor whose genetics are close enough to the patient’s for the marrow to avoid being rejected as foreign.In the family whose teenagers were rid of their suffering, the mother, Sheila Cintron, was so desperate to find a bone-marrow donor for her daughters that she and her husband drained their bank account and maxxed out their credit cards to repeatedly attempt in vitro fertilization and genetic testing of embryos, hoping to have a baby who could be a donor for her girls.She succeeded at last, but her baby was genetically similar to only one of her daughters, Haylee Obando. Haylee had a bone-marrow transplant with her younger brother’s cells and was cured.The other daughter, Helen, was left behind until she was accepted into a clinical trial at Boston Children’s Hospital testing gene therapy for sickle cell disease.Helen Obando has a new life in a new city and is no longer suffering from sickle cell.Ash Ponders for The New York TimesShe too no longer suffers from the disease.I cheered Helen’s gene therapy. Being freed of the disease turned her from a taciturn adolescent whose future held pain, suffering and death at an early age into a teenager like any other. She told me she no longer even thinks about sickle cell.But the pace of the gene therapy trials seems glacial, with few patients enrolled each year. F.D.A. approval is a year or more away, at best.No one expects gene therapy to be the answer for most patients. The cost — which is likely to be $1 million to $2 million for each patient — will be a barrier. And the grueling treatment requires chemotherapy and a month in a specialized hospital.The other family breaks my heart. Dana Jones, is divorced and raising her daughters, Kami and Kyra, alone. Both had disabling strokes before she learned that there was a simple test the girls should have had every year that identifies children with sickle cell at high risk for strokes — strokes that can largely be prevented with a treatment of blood transfusions. The girls are smiley, solicitous and delightful company. But their suffering is immense — weeks and weeks of hospitalizations every year, missed school, and a life of near constant pain that they have learned to accept and not mention until it’s unbearable.Kami and Kyra, still suffering from sickle cell, receive blood transfusionsIlana Panich-Linsman for The New York TimesI asked Ms. Jones if she would want the girls to have gene therapy.“Oh God yes,” she said.She watches Kami and Kyra bravely hide their pain. She has seen emergency room doctors accuse them of faking it to get narcotics. She has seen her girls struggle in school because their strokes impeded their ability to learn. She sees their disease wreaking more damage on their bodies every day.She called and wrote Boston Children’s, asking if Kami and Kyra could enter its trial. They would have to go to Boston for the arduous treatment, but Ms. Jones, who lives in San Antonio, would gladly take them there.She made sure the girls’ names were on a lengthy waiting list for slots in the trial.Now all she can do is wait. And pray.

Read more →