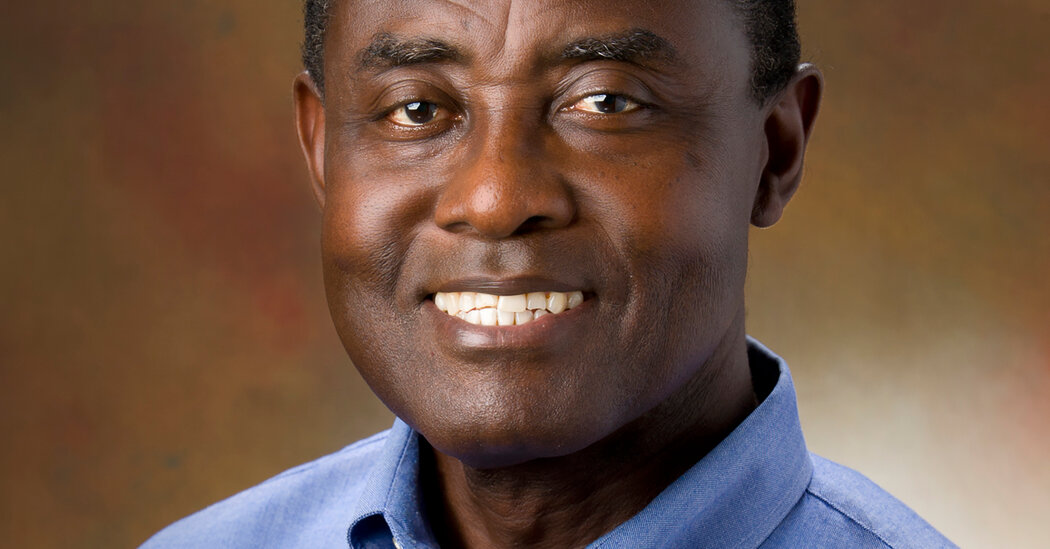

New treatments aim for a gene variant causing the illness in people of sub-Saharan African descent. Some experts worry that focus will neglect other factors.In a Zoom call this spring with 19 leaders of A.M.E. Zion church congregations in North Carolina, Dr. Opeyemi Olabisi, a kidney specialist at Duke University, asked a personal question: How many of you know someone — a friend, a relative, a family member — who has had kidney disease?The anguished replies tumbled out from the assembled pastors:A childhood friend died, leaving a daughter behind.A father and sister felled by the disease.Uncles and sons lost.Three cousins and a brother-in-law on dialysis.None of this surprised Dr. Olabisi, who disclosed that he, too, had lost family members to the disease. His best friend, who had taught him to ride a bike in his native Nigeria, died of kidney failure in his early 30s.Kidney specialists have long known that Black Americans are disproportionately affected by kidney disease. While Black people make up about 12 percent of the U.S. population, they comprise 35 percent of Americans with kidney failure. Black patients tend to contract kidney disease at younger ages, and damage to their organs often progresses faster.Social disparities and systemic racism contribute to this burden, but there is also a genetic factor. Many with sub-Saharan ancestry have a copy of a variant of the gene APOL1 inherited from each parent, which puts them at high risk. Researchers have known for a decade that APOL1 is one of the most powerful genes underlying a common human disease.But there is hope now that much of this suffering can be alleviated. As many as 10 companies are working on drugs to target the APOL1 variants. And Dr. Olabisi has a federal grant to test whether baricitinib, a drug that treats rheumatoid arthritis, can help kidney patients with the variants.Yet the promise of treatments comes with difficult questions.Should genetic testing be offered and, if so, to whom? Although the variants increase risk, they do not preordain kidney disease. If someone knows that they have the variants, will they live in fear of kidney failure?There are as yet no proven ways to reduce the risk of kidney disease in those with two copies of the variants. Rigorous control of blood pressure — a major risk factor for progression of kidney disease — can be difficult to achieve in those who have the variants.“Now we know that the reason you can’t get your blood pressure down is because you have APOL1 kidney disease that is ferociously raising your blood pressure,” said Dr. Jeffrey Kopp, a kidney researcher at the National Institutes of Health. “It’s not your fault.”Despite their elation at the progress being made, some experts like Dr. Olabisi say that a laser focus on variants may let policymakers ignore the social and economic disparities underlying the disease.But, he added, “we don’t want to pretend that the biology doesn’t exist.” That, he said, “would not be doing the community any good.”Dr. Opeyemi Olabisi in the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute in Durham, N.C. He has lost friends and family members to kidney disease.Cornell Watson for The New York TimesA Farmer Provides a ClueWhile it has long been known that kidney failure occurs in African Americans five times as much in as it does in white Americans, “We had never been able to understand all the reasons,” said Dr. Neil Powe, a professor of medicine and an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco.Researchers began looking for a genetic cause. Finally, a little more than a decade ago, a Havard team led by Giulio Genovese, Dr. David Friedman and Dr. Martin Pollak found it: variants of APOL1 that ramped up the gene’s activity.Understand Sickle Cell DiseaseThe rare blood disorder, which can cause debilitating pain, strokes and organ failure, affects 100,000 Americans and millions of people globally, mostly in Africa.The Global Epicenter: In Nigeria, where 150,000 babies are born each year with sickle cell disease, the effects of the condition are pervasive and devastating. On the Edge of Fear: A cure for the disease, which in the United States mostly affects Black people, seems near. For some, it may come too late.Preventing Complications: A legacy of neglect toward Americans with sickle cell means that patients may not receive the treatments needed to stave off the disease’s risks. A Haunting Memory: The Times reporter Gina Kolata shares her experience reporting on the inequities in access to medical advances in the treatment of the disease.It was a complete surprise. APOL1 is part of the immune system and can destroy trypanosomes — protozoa that can cause illnesses. But no one expected it to have anything to do with the kidneys.It turns out that the variants rose to a high frequency among people in sub-Saharan Africa because they offer powerful protection against deadly African sleeping sickness, a disease caused by trypanosomes. It is reminiscent of another gene variant that protects against malaria but causes sickle cell disease in those who inherit two copies. That variant became prominent in parts of Africa and other areas of the world where malaria is common, but sickle cell variants are much less common than APOL1 risk variants.About 39 percent of Black Americans have one copy of the gene’s risk variants; another 13 percent, or nearly 5.5 million, have two copies. Those with two copies are at increased risk for fast progressing kidney disease that often starts in young adulthood. Approximately 15 percent to 20 percent of those with two copies develop kidney disease in their lifetime.In contrast, 7.7 percent of Americans with African ancestry have one copy of the sickle cell variant, and 0.3 percent have two copies.“What nature gave with one hand, it took away with the other,” Dr. Olabisi said.One way to treat kidney disease might be using medicines that block the gene and its variants from acting in the body. But researchers had to find out if APOL1 was necessary for kidney function. If it was, drugs that blocked it might do more harm than good.Researchers found an answer: A farmer in India had no APOL1 gene. His kidneys were totally healthy.Often, in drug development, Dr. Friedman says, the drug dose has to be fine tuned — too much is dangerous and too little is useless. The discovery of the farmer, he said, “tells you you can probably drive the level of the APOL1 protein very low.”But ethical issues have tempered some experts’ enthusiasm about the genetic discoveries.Harriet A. Washington, a lecturer in ethics at Columbia University and author of the book “Medical Apartheid,” worries that knowledge of the role of APOL1 variants can drive the medical establishment toward “a blame-the-victim approach signaling an inherent flaw in African Americans.”The implication, she said: “This is something happening in nature, so what can we do about it?” Such an attitude, she added, “invites futility and absolves health care from treating sufferers.”Joseph L. Graves, Jr., a professor of biological sciences at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, raised another issue. “We don’t want to fall into the myth of the genetically sick African,” he said.“All populations have genetic variants, but the action of those variants is determined by the environment in which those people live,” Dr. Graves explained. “People want to find simple explanations for complex phenomena. Find a genetic variant and make the story simple, but that’s not how it works. Environmental effects are really important.”He added that for Black Americans, profound environmental effects rise from structural racism — inequitable effects of law and policies — which can lead to a lack of access to health care, including preventive care to ward off chronic illness.Erika Blacksher, an ethicist at the nonprofit Center for Practical Bioethics in Kansas City, Mo., added that while finding “a treatment that might counteract the effect of the genetic variant is good news,” she worried that social inequities could not be disentangled from the high rate of kidney disease among those with sub-Saharan African ancestry, not all of whom have the APOL1 variant. Emphasizing the variants, she said, “deflects from our social responsibility to actually change the conditions that contribute to the onset of chronic kidney disease.”Making a PlanMalcolm, left, and Martin Lewis, 26, have lupus, an autoimmune disease that attacks the body’s tissues and organs.Amir Hamja for The New York TimesMartin and Malcolm Lewis, 26-year-old identical twins, have lupus, an autoimmune disease that can ravage the body’s organs. So when Martin developed kidney disease at age 10, his doctors said lupus was to blame.In July 2020, Martin, an actor who lives in Brooklyn, was visiting Malcolm, a data analyst who was hospitalized at Duke with a lupus flare-up. There, the brothers met Dr. Olabisi, who told them about APOL1.They discussed his research project, which involves testing Black Americans and enrolling those with the variant and with kidney disease in a study of the arthritis drug. He invited them to participate and asked if they wanted to know if they had APOL1 variants.“I was all for it,” Malcolm said. So was Martin.When they were tested, the brothers learned they had the variants and that the variants, not lupus, most likely were damaging their kidneys. They hardly knew how to react.“I am still trying to grapple with it,” Malcolm said.But Dr. Olabisi was not surprised. Researchers think the variants cause kidney disease only when there is a secondary factor. A leading candidate is the body’s own antiviral response, interferon, which is produced in abundance in people with lupus.High levels of interferon also occur in people with untreated H.I.V. As happens in people with Covid-19, they can suffer an unusual and catastrophic collapse of their kidneys if they have the variants. Other viral infections, including some that may go unnoticed, can elicit surges of interferon that could set off the APOL1 variants. Interferon is also used as a drug to treat some diseases including cancer and was tested as a treatment for Covid patients.For now, there is little Malcolm and Martin can do except take medications to control their lupus.Martin said he understands all that, but he’s glad he learned he has the variants. Now, he knows what he might be facing.“I’m the kind of person who likes to plan,” he said. “It does make a difference.”From a Gene to DrugsWhile Dr. Olabisi is waiting to start his study, a drug company, Vertex, has forged ahead with its own research. But there was no agreement on how APOL1 variants caused kidney disease, so it was not clear what a drug was supposed to block.“If you don’t understand the mechanism, that means you can’t measure effects in a lab,” said Dr. David Altshuler, chief scientific officer at Vertex. “And if you can’t measure effects in the lab, that means you can’t correct them.”It was known how the APOL1 protein protected against sleeping sickness — it punched holes in the disease-causing trypanosomes, making them swell with fluid and burst.Vertex researchers hypothesized that the variants spurred APOL1 proteins to punch holes not just in trypanosomes but also in kidney cells.What followed was years of work in lab studies and in animals given genes for human APOL1 variants and then screening about a million compounds that might block APOL1.Finally, the researchers settled on a drug that worked in animal models.Vertex tested the experimental drug in a 13-week study in patients with advanced kidney disease. The drug reduced the amount of protein in their urine by 47.6 percent, a sign of improved kidney function.In late March, the company announced it would take the next step — a clinical trial that would enroll approximately 66 patients in the first phase, to find the best dose, and 400 in the next phase, to see if the drug could improve kidney functions in patients with the risk variants and kidney damage and protect them from developing kidney failure or dying.Other companies began later and have revealed less about their plans and progress. AstraZeneca, for example, would only say that it was in the early stages of testing a drug that could bind to APOL1 mRNA, the messenger that carries instructions from the gene to cells’ protein making machinery.MAZE, a small biotech company, is pursuing a strategy similar to the Vertex one, said Dr. Sekar Kathiresan, a co-founder and board member.“I’m optimistic this can move quickly,” Dr. Kathiresan said.Using Their PulpitsAt the meeting with the pastors in North Carolina, Dr. Olabisi said he hoped to test 5,000 Black members of the community for kidney disease with a simple urine test and to use a saliva test to detect APOL1 variants. Testing of the arthritis drug would follow.“I’m in,” said the Rev. Dr. Daran Mitchell, the pastor of Trinity A.M.E. Zion Church in Greensboro, N.C.He and the other pastors were enthusiastic. It would be a community effort, led by people in the community and promoted on social media. Subjects could be tested in churches or in community centers or in their homes. And it was a way to advance the day when a treatment would be available.Dr. Olabisi smiled.“This gives me energy and a lot of hope,” he said.

Read more →