Author: Gina Kolata

These Doctors Admit They Don’t Want Patients With Disabilities

When granted anonymity in focus groups, physicians let their guards down and shared opinions consistent with experiences of many people with disabilities.For a quarter of a century, Dr. Lisa Iezzoni, a professor of medicine at Harvard, has heard the same story during research with hundreds of people who have disabilities: Health care that was substandard. Medical offices that were not accessible. Doctors who did not treat them with respect.“Everywhere I looked, there were disparities,” Dr. Iezzoni said. Yet, what patients told her was no surprise, given her own experiences with multiple sclerosis and using a wheelchair.It was time for the next step.“I thought I needed to start talking to doctors,” Dr. Iezzoni said. She proposed asking physicians what they really thought when a patient with a disability showed up in their offices.The result was a study that gathered doctors, a mix of primary care physicians and specialists recruited from across the United States, into three focus groups on video conferences. Protected by anonymity — only first names or nicknames were used — the groups of eight to 10 doctors began to talk. At first, they were guarded, but as the sessions that Dr. Iezzoni moderated wore on, they began to speak more frankly. In their Zoom meetings, they could not see that Dr. Iezzoni was seated in a wheelchair.The study’s findings, published earlier this month in the journal Health Affairs, stunned one of the study’s authors, Dr. Tara Lagu, professor of medicine and medical social science at Northwestern University.“It was so shocking, I almost couldn’t believe it,” she said.While disability takes many forms, the doctors had much to say about people who use wheelchairs. Some doctors said their office scales could not accommodate wheelchairs, so they had told patients to go to a supermarket, a grain elevator, a cattle processing plant or a zoo to be weighed, or they would tell a new patient the practice was closed.One said he didn’t think he could legally just refuse to see a patient who has a disability — he had to give the patient an appointment. But, he added, “You have to come up with a solution that this is a small facility, we are not doing justice to you, it is better you would be taken care of in a special facility.”More About on Deaf CultureUpending Perceptions: The poetic art of Christine Sun Kim, who was born deaf, challenges viewers to reconsider how they hear and perceive the world. Language in Evolution: Ubiquitous video technology and social media have given deaf people a new way to communicate. They’re using it to transform American Sign Language. Seeking Representation: Though deafness is gaining visibility onscreen, deaf people who rely on hearing devices say their experiences remain mostly untold. Name Signs: Name signs are the equivalent of a first name in some sign languages. We asked a few people to share the story behind theirs.The doctors also explained why they could be so eager to get rid of these patients, focusing on the shrinking amount of time doctors are allotted to spend with individual patients.“Seeing patients at a 15-minute clip is absolutely ridiculous,” one doctor said. “To have someone say, ‘Well we’re still going to see those patients with mild to moderate disability in those time frames’ — it’s just unreasonable and it’s unacceptable to me.”The focus group participants also raised communication difficulties — one doctor said he had hired a sign language interpreter for a deaf patient, a decision which cost so much that he lost $30 each time the patient visited. A specialist in one focus group said disabled patients took too much time, adding that they were “a disruption to clinic flow.”The researchers acknowledged limitations to the study, including that the focus group members were self-selected from verified users of a social network for physicians. The study’s authors said they used research methods to include doctors from a variety of fields and parts of the United States.Dr. Iezzoni said she decided on anonymity for the doctors because she thought it would be difficult to get physicians to openly admit that they treat patients with disabilities differently, and not only because of the legal repercussions of violating the Americans with Disabilities Act. They also “don’t want to come across as horrible people,” she said.August Rocha of Milwaukee said he hesitates to complain and he worries that the doctor might spread the word that he is a difficult patient. “You want the doctor to be on your side,” he said.Kevin Miyazaki for The New York TimesPeople with disabilities who were interviewed for this article said the strategies doctors described to limit their care or get rid of them rang all too true.Jason Miller, 46, who lives in Green Bay, Wis., has a rare bone disorder, osteogenesis imperfecta, and says he has suffered many indignities. For example, when he called a doctor for an appointment, all went well until he mentioned he used a wheelchair. Then, all of a sudden, he said, his appointment was canceled. The person he was speaking to at the doctor’s office said there was a mistake — the doctor was on vacation. They would call back to reschedule. They never did.August Rocha, 27, who lives in Milwaukee, and makes TikTok videos about being transgender and disabled, has Behçet’s disease, a genetic disorder that causes chronic pain. He uses both a wheelchair and a walker. And he says he has heard it all.“Some will find every excuse not to see you. They will say, ‘Our machinery isn’t good enough for you. Maybe you shouldn’t come in.’” Or doctors will have trouble examining him because they cannot get him onto an exam table, so he said they will tell him directly, “I really don’t know what to do with you. Maybe you should go elsewhere.’”He hesitates to complain, “You want the doctor to be on your side,” he said. And he worries that the doctor might spread word that he is a difficult patient, making other doctors spurn him.Dr. Lagu said there are no easy solutions. One change she would like to see, which the National Council on Disability proposed this year, is including disability in the data health care systems collect about their patients. Not doing so makes it impossible to track disparities in treatment and outcomes.“We have data on racial disparities because health systems are forced to collect data on race,” Dr. Lagu said.Doctors need to know ahead of time that they will be seeing a patient with a disability. All too often, Dr. Lagu said, a patient will call and explain their disability, but the doctor’s office does not convey the message to the provider. “At the end of the day, when they get there, the doctor still doesn’t know the patient is coming,” she said.Dr. Iezzoni said accessibility is another high priority for patients. That includes equipment, like exam tables with adjustable heights and scales that can weigh everyone, as well as communication accommodations for those whose hearing, vision or speech is impaired. Many patients also want doctors to have some knowledge about their conditions while appreciating a patient’s extensive knowledge of how disability affects their daily lives.But that is just the start.When it comes to discriminatory thinking around disability, “I know for sure that we have to change the culture of medicine,” Dr. Lagu said.Neelam Bohra

Read more →‘Kind of Awkward’: Doctors Find Themselves on a First-Name Basis

While many physicians may avoid discussing the subject, a study showed that who gets addressed with the honorific “Dr.” may depend on gender, degree and specialty.Dr. Yul Yang, a dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., addresses all of his patients with an honorific — Mr. or Mrs. or Ms. — even if they ask him to use their first names. It is a sign of respect and a way of distinguishing his professional role as a doctor from a more personal role as a friend or confidant. But many patients do not reciprocate, calling him Yul instead of Dr. Yang.He finds that “kind of awkward,” he said, though he lets it pass. But Dr. Yang and his colleagues began to wonder: How often do patients call doctors by their first names?It wasn’t easy to answer this question, but Dr. Yang and his co-authors found a way — by studying tens of thousands of emails that patients sent to doctors at his institution. The results, published last week in the journal JAMA Network Open, appeared to illustrate a few themes about which doctors find themselves on a first-name basis with the people they care for.Female doctors were more than twice as likely as male doctors to be addressed by their first names, as were doctors of osteopathy when compared with doctors with an M.D. behind their name.Men were more likely than women to address doctors by their first name. Patients were more likely to address general practitioners by their first names than specialists.The study found no difference based on age, whether of patient or physician. And the researchers did not examine the race or ethnicity of the patients or doctors.The results, wrote Dr. Lekshmi Santhosh and Dr. Leah Witt of the University of California, San Francisco, in a commentary that accompanied the study, show “a subtle but important form of unconscious bias” against female physicians, general practitioners and doctors of osteopathy.“Use of formal titles in medicine and many other professions is a linguistic signal of respect and professionalism,” they added.Studying this issue, which they refer to as “untitling,” poses a number of challenges. At the Mayo Clinic, at least, “doctors don’t talk about it,” Dr. Yang said. And putting an observer in an exam room would create the medical version of the uncertainty principle: “Once an observer is in there everyone’s behavior will subtly change,” he said.And there is little research to address the issue head on. A previous study, published in 2000, surveyed doctors and found that three quarters of them said some patients addressed them by their first name. But little else was available in the medical literature, and looking at emails offered a novel approach. The medical center supplied Dr. Yang and his colleagues with a trove of email exchanges, allowing analysis of 29,498 messages from 14,958 patients sent from Oct. 1, 2018, to Sept. 30, 2021.The changing behavior they saw in the emails differs from even the recent past when it was all but unheard-of to call doctors by their first names, notes Jonathan Moreno, a professor of history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania. He saw it in his own family, he added.“My father was a psychiatrist with his own sanitarium in Beacon, N.Y., where I grew up,” he said. “Patients, their families, staff, townspeople never addressed him as anything but Dr. or referred to him as ‘the doctor.’ I don’t remember my parents ever referring to his colleagues or their own caregivers as anything but doctor, unless they were close friends.”Popular culture of the 1960s and ’70s reflected that tradition, Dr. Moreno noted, with medical dramas like “Dr. Kildare,” which involved a young intern — Dr. Kildare — and his mentor, Dr. Gillespie. There also was the popular drama “Marcus Welby, M.D.,” starring a kindly family doctor whose patients always called him Dr. Welby but who called patients by their first names. That television tradition seems to be “one of the few that survived into the 21st century,” Dr. Moreno said.Doctors may not enjoy the real world’s tilt toward informality. The survey in 2000 showed that 61 percent were annoyed when patients addressed them by their first name.Their annoyance makes sense, said Debra Roter, an emeritus professor of health, behavior and society at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health. Using a first name can violate the boundary between doctor and patient.“Doctors might find it is undermining their authority,” Dr. Roter said. “There’s a familiarity that first names gives people.”But, she said, the consequences can be greater when a doctor addresses patients by their first names.“It could infantilize the patient or establish the paternalism of the doctor,” she said.Even worse, she said, are other ways some doctors address patients.“I had an experience with a new doctor,” Dr. Roter said. The doctor entered the exam room where she was waiting and said: “Oh hello dear. Please come up to the table.”“I was almost like, ‘Do I know you?’” Dr. Roter said. “I never went back.”

Read more →After Giving Up on Cancer Vaccines, Doctors Start to Find Hope

Encouraging data from preliminary studies are making some doctors feel optimistic about developing immunizations against pancreatic, colon and breast cancers.It seems like an almost impossible dream — a cancer vaccine that would protect healthy people at high risk of cancer. Any incipient malignant cells would be obliterated by the immune system. It would be no different from the way vaccines protect against infectious diseases.However, unlike vaccines for infectious diseases, the promise of cancer vaccines has only dangled in front of researchers, despite their arduous efforts. Now, though, many hope that some success may be nearing in the quest to immunize people against cancer.The first vaccine involves people with a frightening chance of developing pancreatic cancer, one of the most difficult cancers to treat once it is underway. Other vaccine studies involve people at high risk of colon and breast cancer.Of course, such research is in its early days, and the vaccine efforts might fail. But animal data are encouraging, as are some preliminary studies in human patients, and researchers are brimming with newfound optimism.“There is no reason why cancer vaccines would not work if given at the earliest stage,” said Sachet A. Shukla, who directs a cancer vaccine program at MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Cancer vaccines,” he added, “are an idea whose time has come.” (Dr. Shukla owns stock in companies developing cancer vaccines.)That view is a far cry from where the field was a decade ago, when researchers had all but given up. Studies that would have seemed like a pipe dream are now underway.“People would have said this is insane,” said Dr. Susan Domchek, the principal investigator of a breast cancer vaccine study at the University of Pennsylvania.Now, she and others foresee a time when anyone with a precancerous condition or a genetic predisposition to cancer could be vaccinated and protected.“It’s super aspirational, but you’ve got to think big,” Dr. Domchek said.A Less Grim PrognosisDr. Elizabeth Jaffee, deputy director of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University, in 2019.Nina Westervelt for The New York TimesMarilynn Duker knew her family tree was dotted with relatives who had cancer. So when a genetic counselor offered her testing to see if she had any of 30 cancer-causing gene mutations, she readily agreed.The test found a mutation in the gene CDKN2A, which predisposes people who carry it to pancreatic cancer.“They called and said, ‘You have this mutation. There really is nothing you can do,’” recalled Ms. Duker, who lives in Pikesville, Md., and is chief executive of a senior living company.She began having regular scans and endoscopies to examine her pancreas. They revealed a cyst. It has not changed in the past several years. But if it develops into cancer, treatment is likely to fail.Patients like Ms. Duker don’t have many options, noted Dr. Elizabeth Jaffee, deputy director of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University. A person with more advanced cysts could avoid cancer by having their pancreas removed, but that would immediately plunge them into a realm of severe diabetes and digestive problems. The drastic surgery might be worthwhile if it saved their lives, but many precancerous lesions never develop into cancer if they are simply left alone. Yet if the lesions turn into cancer — even if the cancer is caught at an early stage — the prognosis is grim.But it also offers an opportunity to make and test a vaccine, she added.In pancreatic cancer, Dr. Jaffee explained, the first change in normal cells on the path to malignancy almost always is a mutation in a well-known cancer gene, KRAS. Other mutations follow, with six gene mutations driving the cancer’s growth of pancreatic cancer in the majority of patients. That insight allowed Hopkins researchers to devise a vaccine that would train T cells — white blood cells of the immune system — to recognize cells with those mutations and kill them.Their first trial, a safety study, was in 12 patients with early stage pancreatic cancer who already had been treated with surgery. Although their cancer was caught soon after it had emerged and despite the fact that they were treated, pancreatic cancer patients typically have a 70 percent to 80 percent chance of having a recurrence in the next few years. When pancreatic cancer returns, it is metastatic and fatal.Two years later, those patients have not yet had a recurrence.Now, Ms. Duker and another patient have been vaccinated to try to prevent a tumor from starting in the first place.“I am really excited about this opportunity,” she said.The vaccine seems safe, and it has elicited an immune response against the common mutations in this cancer.“So far, so good,” Dr. Jaffee said.But only time will tell if it prevents cancer.‘We Have to Look at Different Patients’Dr. Olivera Finn, a professor in the departments of immunology and surgery at University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.Tom Altany/University of PittsburghIn a sense, the search for cancer vaccines started with Dr. Olivera Finn, a distinguished professor in the departments of immunology and surgery at University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.She began in 1993 with a vaccine directed at the core of a molecule, muc1. In normal cells, the molecule is invisible to the immune system because it is covered in a bush of sugar molecules. But in colon, breast and pancreatic cancers, it can become visible to the immune system. That made it seem like a perfect vaccine target because it could allow the immune system to attack only cancer cells.“We had this trial, 63 patients, Stage 4 cancer. They had failed all therapies,” Dr. Finn said.The first patient had had breast cancer and was treated with a double mastectomy. But the cancer returned.“The tumor was on her chest, thick and red,” she said. “She had two pumps, one emptying liquid from her lungs and the other liquid from her abdomen.”In their initial studies, it became clear to Dr. Finn and her colleagues that the cancers were too far advanced for immunizations to work. After all, she notes, with the exception of rabies, no one vaccinates against an infectious disease in people who are already infected.“I said, ‘I don’t want to do that again,’” Dr. Finn said. “It is not the vaccines. We have to look at different patients.”Now, she and her colleague at Pittsburgh, Dr. Robert Schoen, a gastroenterologist, are trying to prevent precancerous colon polyps with a vaccine. But intercepting cancer can be tricky.They focused on people whose colonoscopies had detected advanced polyps — lumps that can grow in the colon, but only a minority of which turn into cancer. The goal, Dr. Schoen said, was for the vaccine to stimulate the immune system to prevent new polyps.It worked in mice.“I said, ‘OK, this is great,’” Dr. Schoen recalled.But a recently completed study of 102 people at six medical centers randomly assigned to receive the preventive vaccine or a placebo had a different result. All had advanced colon polyps, giving them three times the risk of developing cancer in the next 15 years compared to people with no polyps.Only a quarter of those who got the vaccine developed an immune response, and there was no significant reduction in the rate of polyp recurrences in the vaccinated group.“We need to work on getting a better vaccine,” Dr. Schoen said.Pre-empting a Pre-cancerDr. Mary L. Disis, director of the Cancer Vaccine Institute at the University of Washington.Kiran DhillonDr. Mary L. Disis, director of the Cancer Vaccine Institute at the University of Washington, wants to prevent breast cancer in women with gene variants that put them at high risk. Her initial hopes, though, are more modest.One goal is to help women who have ductal carcinoma in situ, which doctors call a pre-cancer. Surgery is the standard treatment, but because some women also have chemotherapy and radiation to protect themselves from developing invasive breast cancer. “Ideally, a vaccine would replace those treatments,” she said.She began by looking at breast cancer stem cells. These cells, found in early cancers, are resistant to chemotherapy and radiation, and they can metastasize. They drive recurrences of breast cancers, said Dr. Disis, who has received grants from pharmaceutical companies and is a founder of EpiThany, a company that is developing vaccines.Dr. Disis and her colleagues found a number of proteins in these stem cells that were normal but produced at a much higher level in cancer cells than in noncancerous cells. That offered an opportunity to test a vaccine that produced some of those proteins.Their vaccine was tested in women with advanced cancers that were well established. It did not cure the cancers but demonstrated that the vaccine could provide the sort of immune response that might help earlier in the course of the disease.She plans to try vaccinating patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or another precancerous condition, atypical ductal hyperplasia. Her group has a vaccine they developed to target three proteins produced in abnormally high amounts in these lesions.The hope, she said, is to make the lesions shrink or go away before the women have surgery to remove them.“This would be proof the vaccine has a cleansing effect,” she said. If the vaccine succeeds, women may feel comfortable forgoing chemotherapy or surgery.To Paint a Grand Future“I really think we will see a few vaccines approved for clinic in the next five years,” Dr. Disis said. The first vaccines, she predicts, will be used to prevent recurrences in patients whose cancer was successfully treated.“Then, I think we will very rapidly move on to primary prevention,” giving vaccines to healthy people at high risk, she said.Others are similarly optimistic.“At least we know the road map,” said Dr. Shizuko Sei, medical officer of the chemopreventive agent development research group at the National Cancer Institute.“People may disagree, but the answer at this point is, yes, it is possible” to make vaccines to intercept cancer, she said.Dr. Domchek said she can envision a future in which people will have blood tests to find cancer cells so early that they do not show up in scans or standard tests.“To paint a grand future,” she said, “if we knew the tests predicted cancer we could say, ‘Here’s your vaccine.’”

Read more →A Devious Cellular Trick Cancers Can Use to Escape Your Immune System

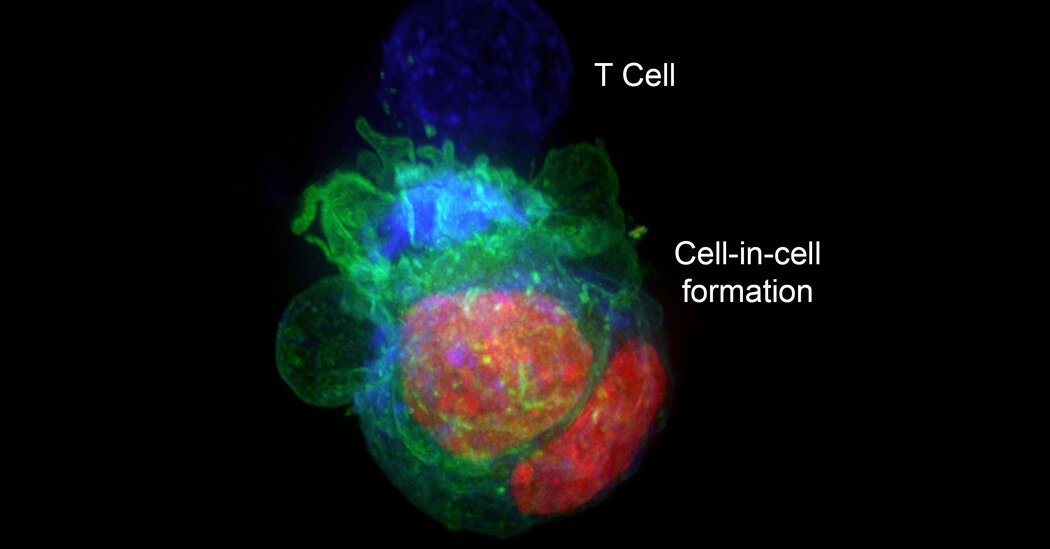

A researcher discovered that giant cells under a microscope were actually cancer cells hiding inside other cancer cells.In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells.The finding, they suggested in an article published this month in the journal eLife, may explain why some cancers can be resistant to treatments that should have destroyed them.The research began when Yaron Carmi, an assistant professor at Tel Aviv University, and Amit Gutwillig, then a doctoral student studying in his lab, were studying which T cells of the immune system might be the most potent in killing cancers. They started with laboratory experiments that examined treatment-resistant melanoma and breast cancers in mice, studying why an attack by T cells that were engineered to destroy those tumors did not obliterate them.They were looking at checkpoint inhibitors, a particular type of cancer therapy. They involve removing proteins that ordinarily block T cells from attacking tumors and are used to treat a variety of cancers, including melanoma, colon cancer and lung cancer. But sometimes, after a tumor seems to have been vanquished by T cells, it bounces back.Dr. Carmi, who loves looking at cells under microscopes, started peering at the tumors while the T cells were attacking them. “I wanted to see the killing, the actual killing,” he said.Every time, though, he saw some giant cells that remained after the T cells had done their job. “I wasn’t sure what it was, so I thought I would take a closer look,” he said.The giant cells turned out to be cancer cells that were harboring other cancer cells, protecting them from destruction. Once the cancer cells escaped to their hiding places, T cells could not get to them, even if the immune system killed the cancer cells that were serving as cellular bunkers.“It was like seeing the devil,” Dr. Carmi said.Cancer cells, he added, can remain in hiding “for weeks or months.”When he removed the T cells from the petri dishes, the cancer cells came out of their shelters.A series of 3-D projections, top, and optical slices, bottom, across the height of tumor cells organized in cell-in-cell formation. The cells’ nuclei are color-coded in green and the cells’ membrane is red.Yaron Carmi and Amit Gutwilling, The Carmi Lab/Tel Aviv UniversityHe looked at human cells from breast cancers, colon cancers and melanomas and saw the same phenomenon. But blood cancers and glioblastomas, the deadly brain cancers, did not form the cell-in-cell structures.Perhaps, Dr. Carmi reasoned, it might be possible to prevent cancer cells from taking refuge. He decided to examine the genes involved in this defense mechanism. Blocking those genes, he discovered, also blocked the ability of T cells to attack the tumors.“I realized this is the limit of what the immune system can do,” Dr. Carmi said. “Our immune systems cannot win.”Others, while fascinated by the discovery, say many questions remain.“It’s definitely an interesting paper with some strong, compelling observations,” said Dr. Michel Sadelain, an immunologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where he heads the center’s gene transfer and gene expression laboratory. But, he asked, how relevant is the finding in disabling immunotherapies in the real world?Dr. Marcela Maus, the director of the cellular immunotherapy program at the Mass General Cancer Center, said the discovery showed what might be a new cancer cell defense mechanism.“We have seen that tumors can hide from the immune system, including a kind of ‘impersonating’ immune cells, but I don’t think we’ve ever seen that tumor cells hide inside each other.” But, she added, “I do think it needs to be replicated to gain full traction.”Dr. Jedd Wolchok, the director of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, had the same reaction.“I’ve heard about cancer cells feeding off themselves, feeding off their neighbors, putting out exosomes,” he said, referring to little pouches of signaling chemicals. “I guess this is the next step — hiding inside your neighbor.”One possible remedy, he said, might be to foil the cancer cells by treating a patient with immunotherapy for a short time, stopping, then treating again. That could be in keeping with new questions about how long patients should be treated with these expensive and toxic drugs. The current advice is to treat for two years. But, Dr. Wolchok said, “many of us are asking, Can you get away with less?”He cautioned, though, that the immunotherapy the Tel Aviv group had used was not a standard one in cancer patients.For now, Dr. Wolchok said, while the discovery is “a really innovative observation,” it remains to be seen whether it will lead to improvements in the treatment of cancer patients.

Read more →‘Sobering’ Study Shows Challenges of Egg Freezing

Data from a fertility center showed many women did not get pregnant because of the age at which they froze their eggs and because they did not preserve enough of them.Claire Evans decided to freeze her eggs six years ago, when she was 36. She had just broken up with her fiancé and was worried that her time to have a baby was running out. A friend, whose own marriage had just ended, suggested the procedure.She took medications to stimulate her ovaries to overproduce eggs, which were frozen to use later and to have a baby at an age when it would be difficult to become pregnant without medical intervention.The procedure of egg-freezing is an increasingly popular, but expensive, option for women who want to delay childbirth. But new research documents some caveats: how old a woman is when she freezes her eggs and how many eggs she freezes make a significant difference in whether she will have a baby. Most women who tried to become pregnant, the study found, did not succeed, often because they had waited until they were too old to freeze eggs and had not frozen enough of them.That note of caution comes from data published this summer in a paper in the journal Fertility and Sterility from the clinic where Ms. Evans froze her eggs — New York University Langone Fertility Center.Dr. Marcelle Cedars, professor and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology at the University of California San Francisco who was not involved in the study, said that although it involved just a single fertility clinic, “it is a center that is unique for its long duration of follow-up.”The data, she said, “are sobering” and “should give women pause.” Dr. Cedars, who is also the president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, or A.S.R.M., added that many women “are overly optimistic” about their chances of having a baby when they freeze their eggs. It is not, as many assume, an insurance policy.“The pregnancy rate is not as good as I think a lot of women think it will be,” she said. “I always tell patients, ‘There’s not a baby in the freezer. There’s a chance to get pregnant.’”The study, led by Dr. Sarah Druckenmiller Cascante, a fellow at N.Y.U. Langone, and Dr. James Grifo, director of the fertility center, reported that the average age when women froze eggs was 38.3. On average, they waited four years to thaw and fertilize their eggs.The overall chance of a live birth from the frozen eggs was 39 percent. But among women who were younger than 38 when they froze their eggs, the live birthrate was 51 percent. It rose to 70 percent if women younger than 38 also thawed 20 or more eggs.The age of the woman when she used the eggs to try to have a baby did not make a difference — all that mattered was how old a woman was when she froze her eggs and how many she froze.“The reality is most eggs don’t make good embryos,” Dr. Grifo said. “The more eggs you have, the better the chance.”According to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the number of healthy women freezing eggs rose to 12,438 in 2020 from 7,193 in 2016. But national data on success rates are pretty much nonexistent, said Dr. Timothy Hickman, president of the society and medical director of CCRM Fertility in Houston.“I commend them for doing the study,” Dr. Hickman said of the N.Y.U. team.Dr. Alan Penzias, a fertility specialist at Boston IVF Fertility Clinic and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center who is chair of the practice committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine said data from his center are consistent with the N.Y.U. study. At his center, he said, women who froze their eggs had just one-third of a chance of having a baby when they thawed them.“Counseling should be clear that there is no guarantee and that the value of delaying having a child must exceed the benefit of delay,” Dr. Penzias said.That trade-off is an issue with his 29-year-old daughter, Rebecca, Dr. Penzias said. Ms. Penzias — who gave him permission to mention her situation and use her name — wants to freeze her eggs because she is studying for a Ph.D. and is not ready to have a baby. Having some eggs frozen would give her peace of mind.Dr. Penzias told her she does not need to freeze her eggs — she has plenty of years of fertility ahead of her — but he considers her reason for freezing sufficient.His wife, a bioethicist and Ms. Penzias’s stepmother, disagrees, and said she should finish her degree, then try to get pregnant without frozen eggs.Ms. Penzias decided to freeze her eggs, planning to do so in October.Before choosing to freeze their eggs, women also must be prepared for substantial costs. Each egg retrieval cycle can cost $10,000, Dr. Hickman said. The number of eggs collected varies from woman to woman, and, for many, the only way to get a sufficient number to make success likely is to have more than one cycle.It costs another $5,000 to $7,000 to thaw and fertilize the eggs, grow embryos in the lab for a few days, then transfer them to the woman’s uterus. Many women, including Ms. Evans, have the embryos tested for chromosomal anomalies. That costs another $3,000. And storage of frozen eggs can cost up to $1,000 a year.Some companies’ health insurance policies cover at least part of the costs. But many do not.Most women end up never using their frozen eggs after paying for egg retrieval and storage, often because they got pregnant on their own.Ms. Evans, though, is a success story. She was young enough when she froze eggs to have a good chance of success and to be able to have eggs retrieved twice to accumulate 20 that could be frozen.She married in 2019 — to the same man she had been engaged to. Last year, she had her eggs thawed and fertilized in a laboratory with her husband’s sperm. Seven months ago, she had a baby girl, Fiona.But the frozen eggs did not work for Ms. Evans’s friend who encouraged her to undergo the procedure. In 2020, she had the 10 or so eggs she’d frozen thawed and fertilized.None developed into viable embryos.

Read more →New Method Improves Speed and Cost of Birth Defect Testing

If the technique is confirmed, women who have had miscarriages or those undergoing prenatal screening may no longer need to rely on centralized testing labs for results.After 10 years of effort, medical researchers at Columbia University have developed a very fast and cheap way to detect the extra or missing chromosomes that most often cause miscarriages or severe birth defects.The method, described Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, takes less than two hours using a palm-size device and costs $200 per use. With current testing procedures, women can end up paying $1,000 to $2,000, often out of pocket.The technique, developed by Dr. Zev Williams, director of the Columbia University Fertility Center, and his colleagues, uses cells and tissues obtained from existing prenatal screening procedures of embryos and fetuses, or tissue obtained after miscarriages. Its key advantage is that the cells or tissue do not have to be sent to a testing lab — the analysis can be done in the same office that obtained the material, and results are ready in hours rather than days or weeks.Dr. Williams’s results still need to be confirmed by outside studies. But if the method were widely used, it could help more women who had lost pregnancies better understand what caused their miscarriages. For women who have embryos tested during in vitro fertilization, it would also avoid lengthy waits for results. The same would be true of women who have prenatal testing of fetuses with amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling, known as C.V.S. And for women in states that have restricted abortion to within the first 15 or 18 weeks of a pregnancy, it could provide a bit more lead time in deciding whether to terminate a pregnancy.Current screening methods, sent to centralized labs, involve lengthy wait times for women. The longest delay in getting test results is for women who have had miscarriages. Those women may have to wait several weeks, because labs must first grow cells in order to have thousands to examine, said Dr. James Grifo, program director of the New York University Langone Fertility Center, who was not involved in the new study.Dr. Mark Hornstein, director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the cultured cells sometimes died before they could be tested.“It is very difficult to keep cells alive and not contaminated for three weeks,” Dr. Hornstein said. “Not infrequently, we get no growth. We wait three weeks, and then the lab tells us, ‘You have no cells.’”The new test avoids these delays by using a method called nanopore sequencing, which was developed to read the sequences of very long strands of DNA but has not been used to look for chromosomal anomalies.Dr. Williams and his colleagues modified the preparation of DNA samples to use nanopore sequencing with small DNA pieces. Each DNA segment should appear as two copies — one from each chromosome. If there are three copies, that means there is an extra chromosome; if there is one copy, that means a chromosome is missing.The new test uses a palm-size device for a method called nanopore sequencing, which was developed to read the sequences of very long strands of DNA. Columbia University Fertility CenterChromosome testing can provide important information for women and their doctors because extra or missing chromosomes are usually fatal to embryos. Fetuses that survive with them often have severe birth defects. The best-known example — Down syndrome — is “actually one of the mildest,” Dr. Williams said.That can be important for in vitro fertilization. The older a woman is, the more likely that an embryo will have chromosomal abnormalities. For 30-year-old women, the risk is 25 percent. It is 75 percent in women at age 42.Women who undergo I.V.F. and who opt to have their embryos tested before implantation usually have to pay for the testing themselves. The embryos are frozen to preserve them while testing goes on. The woman has to wait for the next month’s menstrual cycle for implantation.While test results using tissue from miscarriages take weeks, central labs get results from tests on embryos or fetuses in about three to five days. That is because cells from an embryo or fetus do not grow well in culture, Dr. Grifo explained, so the cells are tested sooner, but with a modest reduction in accuracy.But the new method yields results from those same tests on embryos or fetuses on the same day, within hours.The new test might also help alleviate a problem with prenatal testing in a handful of states that allow abortions only during the first 15 or 18 weeks of pregnancy.Amniocentesis is usually done between 15 and 20 weeks of pregnancy and C.V.S. between the 11th and 14th weeks. If a woman waits days for test results, it might be too late in some states to terminate her pregnancy.Dr. Williams and his colleagues tested their method by examining 218 samples, comparing their results to those from standard tests of the same samples.The results were identical for amniotic fluid and C.V.S. tissues. But in one of the 52 embryos tested, the standard test found an extra chromosome 21, meaning Down syndrome, while the new test did not.“We requested that the clinical lab retest that sample, but they didn’t have any material left to retest, so we can’t determine which result was correct,” Dr. Williams said.Tests of 10 miscarriage samples examined with the new method were different from those of the standard test, but it turned out the standard test was wrong.The group also showed that a group of technicians could quickly learn to do the test and get accurate results.“It’s a great start,” Dr. Grifo said. He added that he would like the accuracy of embryo testing to be 100 percent but said that he was confident that would happen.Dr. Hornstein, who was also not associated with the study, cautioned that the test was not yet ready for widespread use. There need to be independent studies that confirm that its results are accurate, and there must be evidence that it is “technically easy enough that any lab can do it,” he said.But he added that if those conditions are met, he expects the test to be adopted widely.Dr. Williams, who has applied for a patent, said he hoped to offer the test at Columbia soon. He submitted his data to New York State for approval.“Once it’s approved, we are ready to go,” he said.

Read more →A ‘Reversible’ Form of Death? Scientists Revive Cells in Dead Pigs’ Organs.

Researchers who previously revived some brain cells in dead pigs succeeded in repeating the process in more organs.The pigs had been lying dead in the lab for an hour — no blood was circulating in their bodies, their hearts were still, their brain waves flat. Then a group of Yale scientists pumped a custom-made solution into the dead pigs’ bodies with a device similar to a heart-lung machine.What happened next adds questions to what science considers the wall between life and death. Although the pigs were not considered conscious in any way, their seemingly dead cells revived. Their hearts began to beat as the solution, which the scientists called OrganEx, circulated in veins and arteries. Cells in their organs, including the heart, liver, kidneys and brain, were functioning again, and the animals never got stiff like a typical dead pig.Other pigs, dead for an hour, were treated with ECMO, a machine that pumped blood through their bodies. They became stiff, their organs swelled and became damaged, their blood vessels collapsed, and they had purple spots on their backs where blood pooled.The group reported its results Wednesday in Nature.The researchers say their goals are to one day increase the supply of human organs for transplant by allowing doctors to obtain viable organs long after death. And, they say, they hope their technology might also be used to prevent severe damage to hearts after a devastating heart attack or brains after a major stroke.But the findings are just a first step, said Stephen Latham, a bioethicist at Yale University who worked closely with the group. The technology, he emphasized, is “very far away from use in humans.”The group, led by Dr. Nenad Sestan, professor of neuroscience, of comparative medicine, of genetics and of psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine, was stunned by its ability to revive cells.“We did not know what to expect,” said Dr. David Andrijevic, also a neuroscientist at Yale and one of the authors of the paper. “Everything we restored was incredible to us.”Others not associated with the work were similarly astonished.“It’s unbelievable, mind blowing,” said Nita Farahany, a Duke law professor who studies ethical, legal and social implications of emerging technologies.And, Dr. Farahany added, the work raises questions about the definition of death.“We presume death is a thing, it is a state of being,” she said. “Are there forms of death that are reversible. Or not?”The work began a few years ago when the group did a similar experiment with brains from dead pigs from a slaughterhouse. Four hours after the pigs died, the group infused a solution similar to OrganEx that they called BrainEx and saw that brain cells that should be dead could be revived.That led them to ask if they could revive an entire body, said Dr. Zvonimir Vrselja, another member of the Yale team.Representative images of electrocardiogram tracings in the heart, top, immunostainings for albumin in the liver, middle and actin in the kidney, comparing control organs, left, and those treated with OrganEx.David Andrijevic, Zvonimir Vrselja, Taras Lysyy, Shupei Zhang; Sestan Laboratory; Yale School of MedicineThe OrganEx solution contained nutrients, anti-inflammatory medications, drugs to prevent cell death, nerve blockers — substances that dampen the activity of neurons and prevented any possibility of the pigs regaining consciousness — and an artificial hemoglobin mixed with each animal’s own blood.When they treated the dead pigs, the investigators took precautions to make sure the animals did not suffer. The pigs were anesthetized before they were killed by stopping their hearts, and the deep anesthesia continued throughout the experiment. In addition, the nerve blockers in the OrganEx solution stop nerves from firing in order to ensure the brain was not active. The researchers also chilled the animals to slow chemical reactions. Individual brain cells were alive, but there was no indication of any organized global nerve activity in the brain.There was one startling finding: The pigs treated with OrganEx jerked their heads when the researchers injected an iodine contrast solution for imaging. Dr. Latham emphasized that while the reason for the movement was not known, there was no indication of any involvement of the brain.Yale has filed for a patent on the technology. The next step, Dr. Sestan said, will be to see if the organs function properly and could be successfully transplanted. Some time after that, the researchers hope to test whether the method can repair damaged hearts or brains.The journal Nature asked two independent experts to write commentaries about the study. In one, Dr. Robert Porte, a transplant surgeon at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, discussed the possible use of the system to expand the pool of organs available for transplant.In a telephone interview, he explained that OrganEx might in the future be used in situations in which patients are not brain-dead but brain injured to the extent that life support is futile.In most countries, Dr. Porte said, there is a five-minute “no touch” policy after the respirator is turned off and before transplant surgeons remove organs. But, he said, “before you rush to the O.R., additional minutes will pass by,” and by that time organs can be so damaged as to be unusable.And sometimes patients don’t die immediately when life support is ceased, but their hearts beat too feebly for their organs to stay healthy.“In most countries, transplant teams wait two hours” for patients to die, Dr. Porte said. Then, he said, if the patient is not yet dead, they do not try to retrieve organs.As a result, 50 to 60 percent of patients who died after life support was ceased and whose families wanted to donate their organs cannot be donors.If OrganEx could revive those organs, Dr. Porte said, the effect “would be huge” — a vast increase in the number of organs available for transplant.The other comment was by Brendan Parent, a lawyer and ethicist who is director of transplant ethics and policy research at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.In a telephone interview, he discussed what he said were “tricky questions around life and death” that OrganEx raises.“By the accepted medical and legal definition of death, these pigs were dead,” Mr. Parent said. But, he added, “a critical question is: What function and what kind of function would change things?”Would the pigs still be dead if the group did not use nerve blockers in its solution and their brains functioned again? That would create ethical problems if the goal was to preserve organs for transplant and the pigs regained some degree of consciousness during the process.But restoring brain functions could be the goal if the patient had had a severe stroke or was a drowning victim.“If we are going to get this technology to a point where it can help people, we will have to see what happens in the brain without nerve blockers,” Mr. Parent said.In his opinion, the method would eventually have to be tried on people who could benefit, like stroke or drowning victims. But that would require a lot of deliberation by ethicists, neurologists and neuroscientists.“How we get there is going to be a critical question,” Mr. Parent said. “When does the data we have justify making this jump?Another issue is the implications OrganEx might have for the definition of death.If OrganEx continues to show that the length of time after blood and oxygen deprivation before which cells cannot recover is much longer than previously thought, then there has to be a change in the time when it is determined that a person is dead.“It’s weird but no different than what we went through with the development of the ventilator,” Mr. Parent said.“There is a whole population of people who in a different era might have been called dead,” he said.

Read more →After Roe, Pregnant Women With Cancer Diagnoses May Face Wrenching Choices

Urgent questions arise about how care of pregnant women with cancer will change in states where women are unable to terminate pregnanciesIn April of last year, Rachel Brown’s oncologist called with bad news — at age 36, she had an aggressive form of breast cancer. The very next day, she found out she was pregnant after nearly a year of trying with her fiancé to have a baby.She had always said she would never have an abortion. But the choices she faced were wrenching. If she had the chemotherapy that she needed to prevent the spread of her cancer, she could harm her baby. If she didn’t have it, the cancer could spread and kill her. She had two children, ages 2 and 11, who could lose their mother.For Ms. Brown and others in the unlucky sorority of women who receive a cancer diagnosis when they are pregnant, the Supreme Court decision in June, ending the constitutional right to an abortion, can seem like a slap in the face. If the life of a fetus is paramount, a pregnancy can mean a woman cannot get effective treatment for her cancer. One in a thousand women who gets pregnant each year is diagnosed with cancer, meaning thousands of women are facing a serious and possibly fatal disease while they are expecting a baby.Before the Supreme Court decision, a pregnant woman with cancer was already “entering a world with tremendous unknowns,” said Dr. Clifford Hudis, the chief executive officer at the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Now, patients as well as the doctors and hospitals that treat them, are caught up in the added complications of abortion bans.“If a doctor can’t give a drug without fear of damaging a fetus, is that going to compromise outcomes?” Dr. Hudis asked. “It’s a whole new world.”Cancer drugs are dangerous for fetuses in the first trimester. Although older chemotherapy drugs are safe in the second and third trimesters, the safety of the newer and more effective drugs is unknown and doctors are reluctant to give them to pregnant women.About 40 percent of women who are pregnant and have cancer have breast cancer. But other cancers also occur in pregnant women, including blood cancers, cervical and ovarian cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, melanoma, brain cancer, thyroid cancer and pancreatic cancer.Women with some types of cancer, like acute leukemia, often can’t continue with a pregnancy if the cancer is diagnosed in the first trimester. They need to be treated immediately, within days, and the necessary drugs are toxic to a fetus.“In my view, the only medically acceptable option is termination of the pregnancy so that lifesaving treatment can be administered to the mother,” said Dr. Eric Winer, the director of the Yale Cancer Center.Some oncologists say they are not sure what is allowed if a woman lives in a state like Michigan, which has criminalized most abortions but permits them to save the life of the mother. Does leukemia qualify as a reason for an abortion to save her life?“It’s so early we don’t know the answer,” said Dr. N. Lynn Henry, an oncologist at the University of Michigan. “We can’t prove that the drugs caused a problem for the baby, and we can’t prove that withholding the drugs would have a negative outcome.”Cancer drugs are dangerous for fetuses in the first trimester. Though older chemotherapy drugs are safe in the second and third trimesters, the safety of newer drugs is unknown and doctors are reluctant to give them to pregnant women.Bella West/AlamyIn other words, doctors say, complications from a pregnancy — a miscarriage, a premature birth, birth defects or death — can occur whether or not a woman with cancer takes the drugs. If she is not treated and her cancer gallops into a malignancy that kills her, that too might have happened even if she had been given the cancer drugs.Administrators of the University of Michigan’s medical system are not intervening in cancer treatment decisions about how to treat cancers in pregnant women, saying “medical decision making and management is between doctors and patients.”I. Glenn Cohen, a law professor and bioethicist at Harvard, is gravely concerned.“We are putting physicians in a terrible position,” Mr. Cohen said. “I don’t think signing up to be a physician should mean signing up to do jail time,” he added.Oncologists usually are part of a hospital system, Mr. Cohen said, which adds a further complication for doctors who treat cancers in states that ban abortions. “Whatever their personal feelings,” he asked, “what are the risks the hospital system is going to face?”“I don’t think oncologists ever thought this day was coming for them,” Mr. Cohen said.Behind the confusion and concern from doctors are the stories of women like Ms. Brown.She had a large tumor in her left breast and cancer cells in her underarm lymph nodes. The cancer was HER2 positive. Such cancers can spread quickly without treatment. About 15 years ago, the prognosis for women with HER2 positive cancers was among the worst breast cancer prognosis. Then a targeted treatment, trastuzumab, or Herceptin, completely changed the picture. Now women with HER2 tumors have among the best prognoses compared with other breast cancers.But trastuzumab cannot be given during pregnancy.Ms. Brown’s first visit was with a surgical oncologist who, she said, “made it clear that my life would be in danger if I kept my pregnancy because I wouldn’t be able to be treated until the second trimester.” He told her that if she waited for those months passed, her cancer could spread to distant organs and would become fatal.Her treatment in the second trimester would be a mastectomy with removal of all of the lymph nodes in her left armpit, which would have raised her risk of lymphedema, an incurable fluid buildup in her arm. She could start chemotherapy in her second trimester but could not have trastuzumab or radiation treatment.Her next consult was with Dr. Lisa Carey, a breast cancer specialist at the University of North Carolina, who told her that while she could have a mastectomy in the first trimester, before chemotherapy, it was not optimal. Ordinarily, oncologists would give cancer drugs before a mastectomy to shrink the tumor, allowing for a less invasive surgery. If the treatment did not eradicate the tumor, oncologists would try a more aggressive drug treatment after the operation.But if she had a mastectomy before having chemotherapy, it would be impossible to know if the treatment was helping. And what if the drugs were not working? She worried that her cancer could become fatal without her knowing it.She feared that if she tried to keep her pregnancy, she might sacrifice her own life and destroy the lives of her children. And if she delayed making her decision and then had an abortion later in the pregnancy, she feared that the fetus might feel pain.She and her fiancé discussed her options. This pregnancy would be his first biological child.With enormous sadness, they made their decision — she would have a medication abortion. She took the pills one morning when she was six weeks and one day pregnant, and cried all day. She wrote a eulogy for the baby who might have been. She was convinced the baby was going to be a girl, and had named her Hope. She saved the ultrasound of Hope’s heartbeat.“I don’t take that little life lightly,” Ms. Brown said.After she terminated her pregnancy, Ms. Brown was able to start treatment with trastuzumab, along with a cocktail of chemotherapy drugs and radiation. She had a mastectomy, and there was no evidence of cancer at the time of her surgery — a great prognostic sign, Dr. Carey said. She did not need to have all of her lymph nodes removed and did not develop lymphedema.“I feel like it has taken a lot of courage to do what I did,” Ms. Brown said. “As a mother your first instinct is to protect the baby.”But having gone through that grueling treatment, she also wondered how she could ever have handled having a newborn baby and her two other children to care for.“My bones ached. I couldn’t walk more than a few steps without being out of breath. It was hard to get nutrients because of the nausea and vomiting,” she said.The Supreme Court decision hit her hard.“I felt like the reason I did what I did didn’t matter,” she said. “My life didn’t matter, and my children’s lives didn’t matter.”“It didn’t matter if I lost my life because I was being forced to be pregnant,” she said.

Read more →Blood Tests That Detect Cancers Create Risks for Those Who Use Them

The tests screen for cancers that often go undetected, but they are expensive and some experts worry they could lead to unnecessary treatments without saving patients’ lives.Jim Ford considers himself a lucky man: An experimental blood test found his pancreatic cancer when it was at an early stage. It is the among the deadliest of all common cancers and is too often found too late.After scans, a biopsy and surgery, then chemotherapy and radiation, Mr. Ford, 77, who lives in Sacramento, has no detectable cancer.“As my doctor said, I hit the lottery,” he said.Tests like the one that diagnosed him have won praise from President Biden, who made them a priority of his Cancer Moonshot program. A bill in Congress with 254 cosponsors would authorize Medicaid and Medicare to pay for the tests as soon as the Food and Drug Administration approved them.But companies are not waiting for a nod from regulators. One, GRAIL, is selling its annual test, with a list price of $949, in advance of approval, and another company, Exact Sciences, expects to follow suit, using a provision known as laboratory developed tests.The tests, which look for minuscule shards of cancer DNA or proteins, are a new frontier in screening. Companies developing them say they can find dozens of cancers. While standard screening tests are commonly used to detect cancer of the breast, colon, cervix and prostate, but 73 percent of people who die of cancer had cancers that are not detected by standard tests.Supporters say the tests can slash cancer death rates by finding tumors when they are still small and curable. But a definitive study to determine whether the tests prevent cancer deaths would have to involve more than a million healthy adults randomly assigned to have an annual blood test for cancer or not. Results would take a decade or longer.“We’re at a point now where the blood tests are in their early days,” said Dr. Tomasz Beer, a cancer researcher at Oregon Health & Science University, who is directing a GRAIL-sponsored study of the test that found Mr. Ford’s cancer. “Some people in an informed manner can choose to be early adapters.”The companies would like to get the tests approved with studies less rigorous than the F.D.A. typically requires, and they stand to make huge profits if that happens.“GRAIL proposes to test every Medicare beneficiary every year, making it the screening test that could bankrupt Medicare,” said Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, a senior investigator in the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.With 44 million Medicare beneficiaries and an annual test costing about $1,000 a year plus expensive scans and biopsies for those whose tests are positive, the price tag could be substantial.He and other critics warn that the risks of unleashing the tests are substantial. Paradoxical as it may sound, finding cancers earlier could mean just as many deaths, with the same timing as without early diagnosis. That is because — at least with current treatments — cancers destined to kill are not necessarily cured if found early.And there are other risks. For example, some will have a positive test, but doctors will be unable to locate the cancer. Others will be treated aggressively with surgery or chemotherapy for cancers that, if left alone, would not have grown and spread and may even have gone away.Dr. Beer acknowledges that a cancer blood test “doesn’t come without risks or costs, and it is not going to detect every cancer.”But, he said, “I think there’s promise for a real impact.”Others experts are worried.Dr. Barnett Kramer, a member of the Lisa Schwartz Foundation for Truth in Medicine and former director of the Division of Cancer Prevention at the National Cancer Institute, fears that the tests will come into widespread use without ever showing they are beneficial. Once that happens, he said, “it is difficult to unring the bell.”“I hope we are not halfway through a nightmare,” Dr. Kramer said.The Damocles SyndromeWhen Susan Iorio Bell, 73, a nurse who lives in Forty Fort, Pa., saw an ad on Facebook recruiting women her age for a study of a cancer blood test, she immediately signed up. It fit with her advocacy for preventive medicine and her belief in clinical trials.The study was of a test, now owned by Exact Sciences, that involved women who are patients with Geisinger, a large health care network. The test looks for proteins and DNA shed by tumors.Ms. Bell’s result was troubling: Alpha-fetoprotein turned up in her blood, which can signal liver or ovarian cancer.She was worried — her father had had colon cancer and her mother had breast cancer.Ms. Bell had seen what happened when patients get a dire prognosis. “All of a sudden, your life can be changed overnight,” she said.But a PET scan and abdominal M.R.I. failed to find a tumor. Is the test result a false positive, or does she have a tumor too small to be seen? For now, it is impossible to know. All Ms. Bell can do is have regular cancer screenings and monitoring of her liver function.“I just go day by day,” she said. “I am a faith-based person and believe God has a plan for me. Good or bad, it’s his will.”Some cancer experts say Ms. Bell’s experience exemplifies a concern with the blood tests. The situation may involve only a small percentage of people because most who are tested will be told their test did not find cancer. Among those whose tests detect cancer, scans or biopsies can often locate it.But Dr. Susan Domchek, a breast cancer researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, warned that when large numbers of people get tested, false positives become “a real problem,” adding, “we need to know what to do with those results and what they mean.”Dr. Daniel Hayes, a breast cancer researcher at the University of Michigan, refers to the situation as a Damocles syndrome: “You’ve got this thing hanging over your head, but you don’t know what to do about it.”How Good Are the Tests?So far, the Geisinger study is the only published one asking whether the blood tests find early, undetected cancers.In addition to Ms. Bell, the study involved 10,000 women aged 65 to 75 who had the blood test and were encouraged to also have routine cancer screening.The blood test found 26 patients who had cancers: two lymphomas, one thyroid cancer, one breast cancer, nine lung cancers, one kidney cancer, two colorectal cancers, one cancer of the appendix, two cancers of the uterus, six ovarian cancers and one unknown case in which there were cancer cells in the woman’s body but it was not clear where the cancer started.Seventeen of these women, or 65 percent, had early stage disease.Conventional screening found an additional 24 cancers that the blood tests missed.Dr. Bert Vogelstein, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins Medicine who helped to develop the test, said the study was not designed to show risks and benefits. That will require much larger and more detailed studies.GRAIL’s study, led by Dr. Beer, involved 6,629 participants. Its interim data, presented at a professional meeting last year, showed the test found cancer signals in 92 participants. After these subjects had additional tests like CT and PET scans and biopsies, the researchers concluded that 29 had cancer. Among those cancers, 23 were new cancers and nine were early stage. The rest were recurrences in people who had already had cancer.New Developments in Cancer ResearchCard 1 of 7Progress in the field.

Read more →