What Nearly Brainless Rodents Know About Weight Loss and Hunger

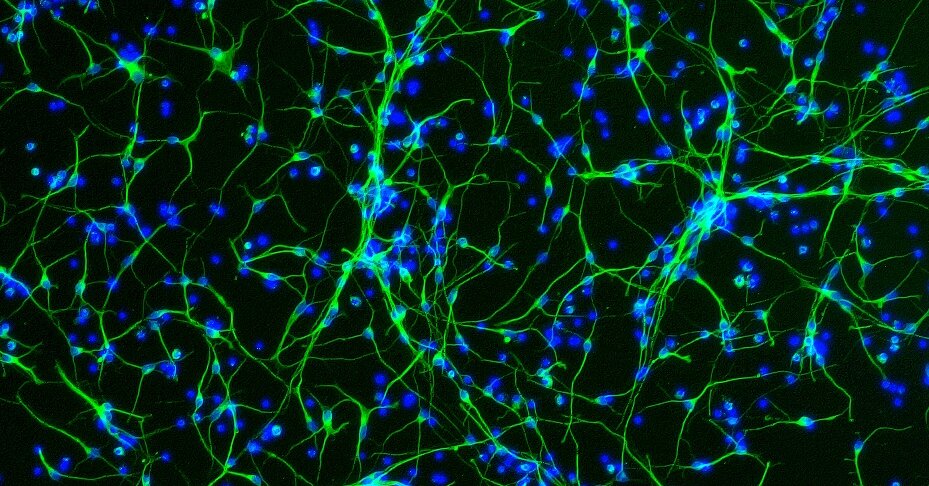

Studies in neuroscience with applications to humans offer clues about what makes us start eating, and when we stop.Do we really have free will when it comes to eating? It’s a vexing question that is at the heart of why so many people find it so difficult to stick to a diet.To get answers, one neuroscientist, Harvey J. Grill of the University of Pennsylvania, turned to rats and asked what would happen if he removed all of their brains except their brainstems. The brainstem controls basic functions like heart rate and breathing. But the animals could not smell, could not see, could not remember.Would they know when they had consumed enough calories?To find out, Dr. Grill dripped liquid food into their mouths.“When they reached a stopping point, they allowed the food to drain out of their mouths,” he said.Those studies, initiated decades ago, were a starting point for a body of research that has continually surprised scientists and driven home that how full animals feel has nothing to do with consciousness. The work has gained more relevance as scientists puzzle out how exactly the new drugs that cause weight loss, commonly called GLP-1s and including Ozempic, affect the brain’s eating-control systems.The story that is emerging does not explain why some people get obese and others do not. Instead, it offers clues about what makes us start eating, and when we stop.While most of the studies were in rodents, it defies belief to think that humans are somehow different, said Dr. Jeffrey Friedman, an obesity researcher at Rockefeller University in New York. Humans, he said, are subject to billions of years of evolution leading to elaborate neural pathways that control when to eat and when to stop eating.We are having trouble retrieving the article content.Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.Thank you for your patience while we verify access.Already a subscriber? Log in.Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Read more →