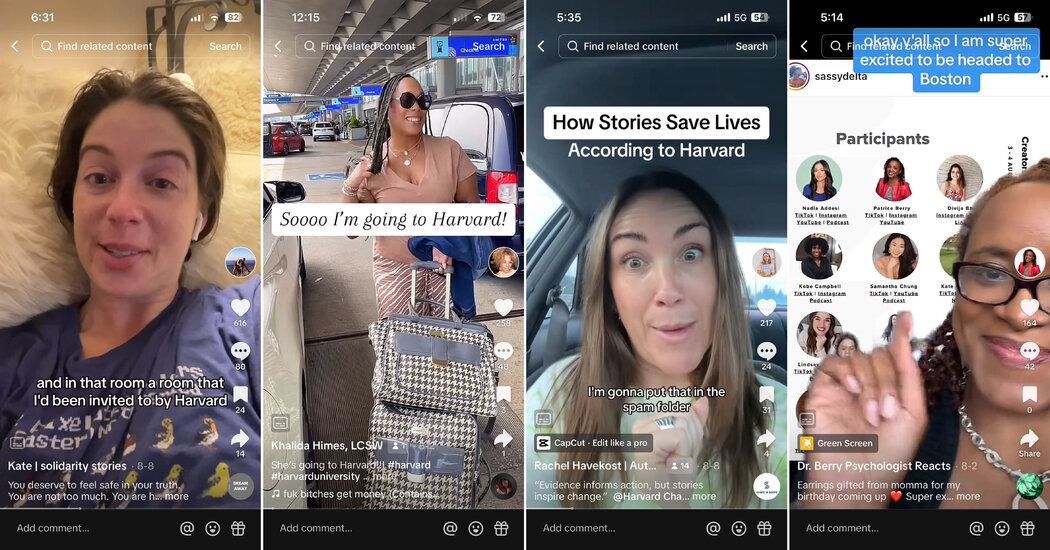

As young Americans turn to TikTok for information on mental health, the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard is building its own team of influencers.One day in February, an invitation from Harvard University arrived in the inbox of Rachel Havekost, a TikTok mental health influencer and part-time bartender in Seattle who likes to joke that her main qualification is 19 years of therapy.The same email arrived for Trey Tucker, a.k.a. @ruggedcounseling, a therapist from Chattanooga, Tenn., who discusses attachment styles on his TikTok account, sometimes while loading bales of hay onto the bed of a pickup truck.The invitations also made their way to Bryce Spencer-Jones, who talks his viewers through breakups while gazing tenderly into the camera, and to Kate Speer, who narrates her bouts of depression with wry humor, confiding that she has not brushed her teeth for days.Twenty-five recipients glanced over the emails, which invited them to collaborate with social scientists at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard. They were not accustomed to being treated with respect by academia; several concluded that the letters were pranks or phishing attempts and deleted them.They did not know — how could they? — that a team of researchers had been observing them for weeks, winnowing down an army of mental health influencers into a few dozen heavyweights selected for their reach and quality.The surgeon general has described the mental health of young people in America as “the defining public health crisis of our time.” For this vulnerable, hard-to-reach population, social media serves as a primary source of information. And so, for a few months this spring, the influencers became part of a field experiment, in which social scientists attempted to inject evidence-based content into their feeds.

@kate__speer Calling all people pleasers! 🙃💁🏻♀️ #anxiety #peoplepleasingrecovery #peoplepleaser #peoplepleasing #peoplepleasingendsnow #recovery #mentalhealthhack #mentalhealthlifehack #ocd #exposuretherapy ♬ Good Vibes (Instrumental) – Ellen Once Again “People are looking for information, and the things that they are watching are TikTok and Instagram and YouTube,” said Amanda Yarnell, senior director of the Chan School’s Center for Health Communication. “Who are the media gatekeepers in those areas? Those are these creators. So we were looking at, how do we map onto that new reality?”The answer to that question became clear in August, when a van carrying a dozen influencers pulled up beside the campus of Harvard Medical School. Everything about the space, its Ionic columns and Latin mottos carved in granite, told the visitors that they had arrived at the high temple of the medical establishment.Each of the visitors resembled their audience: tattooed, in baseball caps or cowboy boots or chunky earrings that spelled the word LOVE. Some were psychologists or psychiatrists whose TikToks were a side gig. Others had built franchises by talking frankly about their own experiences with mental illness, describing eating disorders, selective mutism and suicide attempts.On the velvety Quad of the medical school, they looked like tourists or day-trippers. But together, across platforms, they commanded an audience of 10 million users.Step 1: The subjectsFrom left, screenshots of the TikTok feeds of Ms. Speer, Khalida Himes, Rachel Havekost and Dr. Patrice Berry.Samantha Chung, 30, who posts under the handle @simplifying.sam, could never explain to her mother what she did for a living.She is not a mental health clinician — until recently, she worked as a real estate agent. But two years ago, a TikTok video she made on “manifesting,” or using the mind to bring about desired change, attracted so much attention that she realized she could charge money for one-on-one coaching, and quit her day job.At first, Ms. Chung booked one-hour appointments for $90, but demand remained so high that she now offers counseling in three- and six-month “containers.” She sees no need to go to graduate school or get a license; her approach, as she puts it, “helps clients feel empowered rather than diagnosed.” She has a podcast, a book project and 813,000 followers on TikTok.This accomplishment, however, meant little to her parents, immigrants from Korea who had hoped she would become a doctor. “I really just thought of myself as someone who makes videos in their apartment,” Ms. Chung said.The work of an influencer can be isolating and draining, far from the sunlit glamour that many imagine. Ms. Havekost, 34, was struggling with whether she could even continue. After years of battling an eating disorder, she was feeling stable, which did not generate mental health content; that was one problem.

@rachelhavekost this is your sign🦋🥰. “dance it out” merch is now up on my website🌈💃🏼boogie over the 🔗in my bio or type rachelhavekost.com/merch in your browser🎯🍟! I love you all SO MUCH!!! #dancetoheal #danceitout #somatichealing #somaticshaking ♬ ILYAF (I love you always forever) – Donna Lewis & Digital Farm Animals The other problem was money. She is fastidious about endorsement deals, and still has to tend bar part time to make ends meet. “I’ve turned down an ice cream brand that wanted to pay me a lot of money to post a TikTok saying it was low sugar,” Ms. Havekost said. “That sucked, because I had to turn down my rent.”At Harvard, the influencers were treated like dignitaries, provided with branded merchandise and buffet lunches as they listened to lectures on air quality and health communication. From time to time, the lecturers broke into jargon, referring to multivariate regression models and the Bronfenbrenner model of behavior theory.During a break, Jaime Mahler, a licensed counselor from New York, remarked on this. In her videos, she prides herself on distilling complex clinical ideas into digestible nuggets. In this respect, she said, Harvard could learn a lot from TikTok.“She kept using the word ‘heuristics,’ and that was actually a genuine distraction for me,” Ms. Mahler said of one lecturer. “I remembered her telling me what it was in the beginning, and I didn’t want to Google it, and I kept getting distracted. I was like, Oh, she used it again.”But the main thing the guests wanted to express was gratitude. “I spent my 20s in a psychiatric ward trying to graduate from college,” said Ms. Speer, 36. “Walking into these rooms at Harvard and being held lovingly — honestly, it is nothing more than miraculous.”Ms. Chung was so inspired that she told the assembled crowd that she would now post as an activist. “I am walking out of this knowing the truth, which is that I am a public health leader,” she said. When Meng Meng Xu, one of the researchers on the Harvard team, heard that, she got goose bumps. This was exactly what she had been hoping for.Step 2: The field experimentAmanda Yarnell, senior director of the Chan School’s Center for Health Communication. “People are looking for information, and the things that they are watching are TikTok and Instagram and YouTube,” she said.Sarah Blesener for The New York TimesMany academics take a dim view of mental health TikTok, viewing it as a Wild West of unscientific advice and overgeneralization. Social media, researchers have found, often undermines established medical guidelines, warning viewers off evidence-based treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy or antidepressants, while boosting interest in risky, untested approaches like semen retention.TikTok, which has grappled with how to moderate such content, said recently that it would direct users searching for a range of conditions like depression or anxiety to information from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Cleveland Clinic.At their worst, researchers said, social media feeds can serve as a dark echo chamber, barraging vulnerable young people with messages about self-harm or eating disorders.“Your heart just sinks,” said Corey H. Basch, a professor of public health from William Paterson University who led a 2022 study analyzing 100 TikTok videos with the hashtag #mentalhealth.“If you’re feeling low and you have a dismal outlook, and for some reason that’s what you are drawn to, you will go down this rabbit hole,” she said. “And you could just sit there for hours watching videos of people who just want to die.”Ms. Basch doubted that content creators could prove to be useful partners for public health. “Influencers are in the business of making money for their content,” she said.Ms. Yarnell does not share this opinion. A chemist who pivoted to journalism, she found TikTok “a rich and exciting place” for scientists. She views influencers — she prefers the more respectful term “creators” — not as click-hungry amateurs but as independent media companies, making careful choices about partnerships and, at times, being motivated by altruism.In addition, she said, they are good at what they do. “They understand what their audience needs,” Ms. Yarnell said. “They’ve done a huge amount of storytelling that has allowed stigma to fall away. They have been a huge part of convincing people to talk about different mental health concerns. They are a perfect translation partner.”This is not the first time that Harvard’s public health experts have tried to hitch a ride with popular culture. In 1988, as part of a campaign to prevent traffic fatalities, researchers asked writers for prime-time television programs like “Cheers” and “L.A. Law” to write in references to “designated drivers,” a concept that was, at the time, entirely new to Americans. That effort was famously successful; by 1991, the phrase was so common that it appeared in Webster’s dictionary.

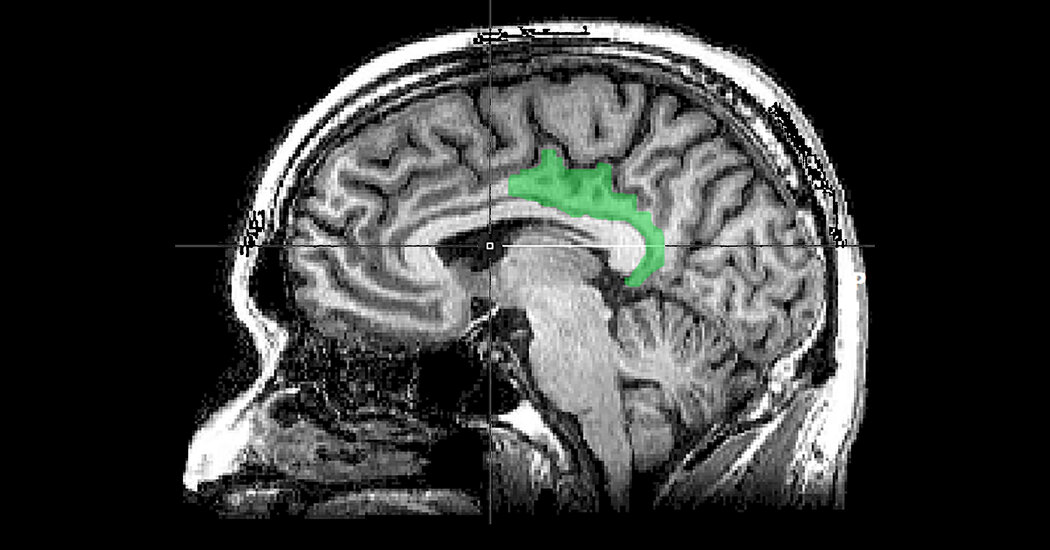

@latinxtherapy Insurances can be so unfair (at least in california) to #mentalhealth providers #latinxtherapy #directory ♬ original sound – shawty bae 🥥🫦 Inspired by this effort, Ms. Yarnell designed an experiment to determine whether influencers could be persuaded to disseminate more evidence-based information. First, her team developed a pool of 105 influencers who were both prominent and responsible: no diet-pill endorsements, no “five signs you have A.D.H.D.”The influencers would not be paid but, ideally, would be won over to the cause. Forty-two of them agreed to be part of the study and received digital tool kits organized into five “core themes”: difficulty accessing care, intergenerational trauma, mind-body links, the effect of racism on mental health and climate anxiety.A smaller group of 25 influencers also received lavish, in-person attention. They were invited to hourlong virtual forums, united on a group Slack channel and, finally, hosted at Harvard. But the core themes were what the researchers were watching. They would keep an eye on the influencers’ feeds and measure how much of Harvard’s material had ended up online.Step 3: This study is not without limitationsA month after the gathering, Ms. Havekost was once again feeling depleted. It wasn’t that she didn’t care about her duty as a public health leader — on the contrary, she said, “every time I post something now, I think about Harvard.”But she saw no simple way to integrate public health messages into her videos, which frequently feature her dancing uninhibitedly, or gazing at the viewer with an expression of unconditional love while text scrolls past. Her audience knows her communication style, she said; study citations wouldn’t feel any more authentic than cleavage enhancement.Mr. Tucker, back in Chattanooga, reached a similar conclusion. He has 1.1 million TikTok followers, so he knows which themes attract viewers. Trauma, anxiety, toxic relationships, narcissistic personalities, “those are the catnip, so to speak,” he said. “Basically, stuff that feeds the victim mentality.”He had tried a couple of videos based on Harvard research — for example, on the way the brain responds to the sound of water — but they had performed poorly with his audience, something he thought might be a function of the platform’s algorithm.“They are not really trying to help spread good research,” Mr. Tucker said. “They are trying to keep eyeballs engaged so they can keep watch times as long as possible and pass that onto advertisers.”It was different for Ms. Speer. After returning from Harvard, she received an email from S. Bryn Austin, a professor of social and behavioral sciences and a specialist in eating disorders, proposing that they collaborate on a campaign to prohibit the sale of weight-loss pills to minors in New York State.Ms. Speer was elated. She got to work putting together a sizzle reel and a grant proposal. As summer turned to fall, her life seemed to have turned a corner. “That’s what I want to do,” she said. “I want to do it for good, instead of, you know, for lip gloss.”Step 4: System-level effectsDr. Sasha Hamdani, a psychiatrist and TikTok creator, center, with Ifelola Ojuri, of YouTube Health, right, and Ms. Speer during a panel discussion in New York City.Sarah Blesener for The New York TimesLast week, in a conference room overlooking the Hudson River, Ms. Yarnell and one of her co-authors, Matt Motta, of Boston University, presented the results of the experiment.It had worked, they announced. The 42 influencers who received Harvard’s talking points were 3 percent more likely to post content on the core themes researchers had fed them. Although that may seem like a small effect, Dr. Motta said, each influencer had such a large audience that the additional content was viewed 800,000 times.These successes bore little resemblance to peer-reviewed studies. They looked like @drkojosarfo, a psychiatric nurse practitioner with 2.4 million followers, dancing in a galley kitchen alongside text on the mind-body link, or the user @latinxtherapy throwing shade on insurance companies while lip-syncing to the influencer Shawty Bae.The uptake seemed to be driven by the distribution of written materials, with no additional effect among subjects who had deep interactions with Harvard faculty. That was unexpected, Ms. Yarnell said, but it was good news, since digital tool kits are cheap and easy to scale.“It’s simpler than we thought,” she said. “These written materials are useful to creators.”But the biggest effect was something that did not show up in the data: the formation of new relationships. Seated beside Ms. Yarnell as she presented the experiment’s results were two of its subjects: Ms. Speer, with her service dog, Waffle, who is trained to paw at her when he smells elevated cortisol in her sweat, and Dr. Sasha Hamdani, a psychiatrist in Kansas who presents information on A.D.H.D. to the accompaniment of sea shanties.Contact had been made. In the audience, the Brooklyn-dad influencer Timm Chiusano was wondering about how to build his own partnership with Harvard’s School of Public Health. “I’m going to 1,000 percent download that tool kit as soon as I can,” he said.But who was boosting who? Ms. Mahler, who was promoting a new book on toxic relationships, sounded a little sad when she considered her partners in academia. “Harvard has this abundant knowledge base,” she said, “if they can just find a way of connecting to the people doing the digesting.”She had learned a great deal about scientists. In some cases, Ms. Mahler said, they spend 10 years on a research project, publish an article, “and maybe it gets picked up, but sometimes it never reaches the general public in a way that really changes the conversation.”“My heart kind of breaks for those people,” she said.

Read more →