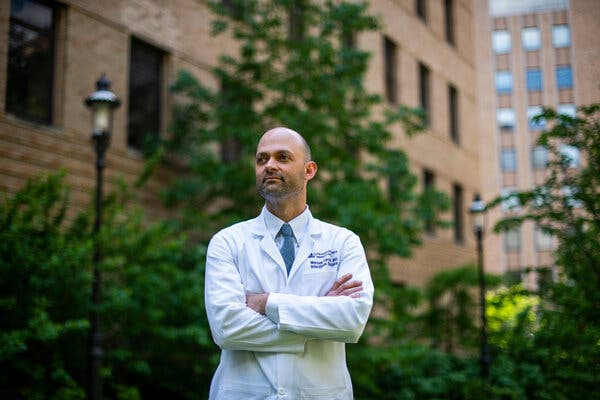

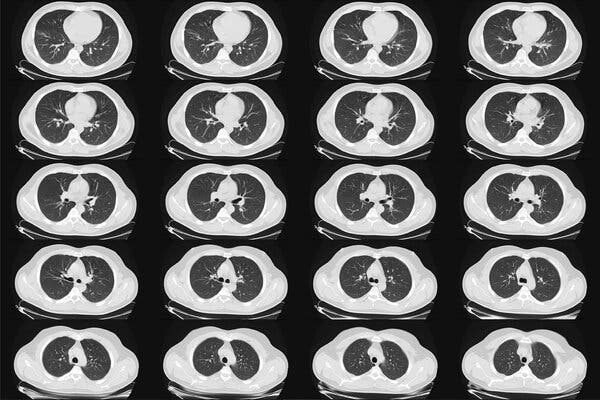

Infected early in the pandemic, Dr. Tomoaki Kato, a renowned transplant surgeon, was soon on life support, and one of the sickest patients in his own hospital.Early in the pandemic, as hospitals in New York began postponing operations to make way for the flood of Covid-19 cases, Dr. Tomoaki Kato continued to perform surgery. Patients still needed liver transplants, and some were too sick to wait.At 56, Dr. Kato was healthy and exceptionally fit. He had run the New York City Marathon seven times, and he specialized in operations that were also marathons, lasting 12 or 16 or 20 hours. He was renowned for surgical innovations, deft hands and sheer stamina. At NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, where he was the surgical director of adult and pediatric liver and intestinal transplantation, his boss has called him “our Michael Jordan.”Dr. Kato became ill with Covid-19 in March 2020.“I was in a denial situation,” he said. “I thought I was going to be fine.”But he soon became one of the sickest patients in his own hospital, dependent on a ventilator and other machines to pump oxygen into his bloodstream and do the work of his failing kidneys. He came close to death “many, many times,” according to Dr. Marcus R. Pereira, who oversaw Dr. Kato’s care and is the medical director of the center’s infectious disease program for transplant recipients.Colleagues feared at first that he would not survive and then, when the worst had passed, that he might never be able to perform surgery again. But after two months in the hospital, Dr. Kato emerged with a determination to get back to work and a new sense of urgency about the need to teach other surgeons the innovative operations he had developed. His own illness also enabled him to connect with patients in ways that had not been possible before.“I really never understood well enough how patients feel,” he said. “Even though I’m convincing patients to take a feeding tube, and encouraging them, saying, ‘Even though it looks like hell now, it will get better and you’ll get through it,’ I really never understood what that hell means.”He approaches those moments differently now: “‘I was there’ are very powerful words for patients.”Dr. Kato was infected before most doctors in New York understood the siege that lay ahead.“When we really realized something serious was coming, I think it was already there,” Dr. Kato said. “No one realized how much the virus had spread through the city. The virus was everywhere.”Dr. Marcus Pereira, who oversaw Dr. Kato’s care. “He looked very sick from the moment he got here, and you realize, this potentially might not end up well,” he said. “It was a very shocking moment.”Joshua Bright for The New York TimesHis illness began with a bad backache, and then fevers that went up and down for a few days. He stayed home, periodically checking his oxygen level, and getting readings of 93 and 94 percent — results now recognized as a possible sign of Covid pneumonia.But at that early point in the pandemic, he said, “Nobody knows what Covid pneumonia is.” And he did not feel very sick, he told colleagues who kept in touch by phone.Dr. Pereira said: “I think that fooled us for a few days while he was at home. His oxygen levels were a little low, but he said, ‘I feel fine,’ and his heart rate was not that fast. He was one of the first-wave patients, and we were still learning about Covid.”‘An eye-opening moment’One morning in the shower Dr. Kato suddenly could not breathe, and he began coughing violently. He tested his oxygen again: It was dangerously low, below 90 percent. He had resisted being hospitalized, as doctors often do, but now he had no choice.“That’s when I decided to check into the hospital,” he said.Dr. Pereira, a friend as well as a colleague, was stunned by Dr. Kato’s condition.“When we actually saw him in the hospital, it was an eye-opening moment,” Dr. Pereira said. “He looked very sick from the moment he got here, and you realize, this potentially might not end up well. It was a very shocking moment. His oxygen levels were very low, he was breathing very rapidly, his heart rate was going very fast, his chest X-ray looked like he had severe Covid.”By the next day, Dr. Kato was on a ventilator.“From there,” he said, “I have no consciousness for about four weeks.”His condition worsened. Bacterial infections set in, followed by sepsis. His kidneys began to fail, and he needed dialysis. His lungs could not work well enough to use the oxygen from the ventilator, and in the middle of one desperate night a surgeon was called in to connect him to a machine that would take over for his lungs by pumping oxygen directly into his blood and taking carbon dioxide out.The machine — called ECMO, for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation — is a last resort.“When someone is on ECMO, you’re suddenly into the absolute highest-mortality group,” Dr. Pereira said. “Your chances of coming back from that are in the single digits. When he went on that, it was sort of a moment. We all felt we were about to lose him.”Dr. Kato was a star, a towering figure in his field, and to see him struck down shook the hospital staff.“It was horrific,” said Dr. Jean C. Emond, the chief of transplant services, and Dr. Kato’s boss. “It was a terrible thing touching a friend and colleague. There was this fear like, Was the world going to end — this global sense of doom. A fear of surfaces. Would you bring it home on your shoes? That deep emotional context of both the global and the personal was happening at once.”People in the highest levels of leadership at the hospital kept asking how Dr. Kato was doing.“His survival represented the fate of all, in a funny way,” Dr. Emond said.A Covid patient in Billings, Mont., hooked up to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. “When someone is on ECMO, you’re suddenly into the absolute highest-mortality group,” Dr. Pereira said.Larry Mayer/The Billings Gazette, via Associated PressPushing the limits in surgeryDr. Emond in 2008 had lured Dr. Kato away from the University of Miami, for his rare expertise in intestinal transplants and so-called ex vivo operations for cancer, in which the surgeon cuts out abdominal organs to get at hard-to-reach tumors, and then sews the organs back in. Most important, Dr. Emond saw in Dr. Kato a willingness to push the limits of what could be done surgically to help patients.“He brought his culture of innovation,” Dr. Emond said. “And his personal capability, his ability to work for long hours, never quitting, never giving up, no matter how difficult the situation, carrying out operations that many would deem impossible.”In his first year at Columbia, Dr. Kato and his team operated successfully on a 7-year-old girl, Heather McNamara, whose family had been told by several other hospitals that her abdominal cancer was inoperable. The surgery, which involved removing six organs and then putting them back in, took 23 hours.More and more patients from around the country, and around the world, began seeking out Dr. Kato for operations that other hospitals could not or would not perform. He had also begun making trips to Venezuela to perform liver transplants for children and teach the procedure to local surgeons, and he created a foundation to help support the work there as well as in other Latin American countries.As Dr. Kato’s colleagues struggled to save him, a waiting list of surgical patients clung to hopes that he would soon be able to save them.Gradually, Dr. Pereira said, there were signs of recovery.“You come in early in the morning to see him,” he said. “The hospital hallways are empty and everybody’s looking at each other, scared and anxious. You go into the intensive care unit dreading bad news, and the team is giving you a sort of hopeful thumbs-up that maybe he’s looking better.”Dr. Kato spent about a month on a ventilator, and a week on ECMO. Like many people with severe Covid, he was tormented by frightening and vivid hallucinations and delusions. In one, he was arrested at the Battle of Waterloo. In another, he had been deliberately infected with anthrax; only a hospital in Antwerp could save him, but he could not get there. He saw the white light that some people describe after near-death experiences. “I felt like I died,” he said.He had spent much of his adult life in hospitals, but never as a patient.“I never got sick,” he said. “I had never faced the reality of death.”When he was finally freed of the machines and breathing on his own, his doctors were elated.But the joy faded when he regained full consciousness and it was clear he was not himself. He was still caught up in the delusions. More worrisome, he seemed confused, his razor-sharp mind not fully back.“I wasn’t making sense,” Dr. Kato said.Scans found a blood clot and a hemorrhage in Dr. Kato’s brain. Although not severe, they were still troubling.“I remember seeing him, and not seeing him the way I wanted him to be,” Dr. Pereira said, adding that at the end of one day, “I went to my car and broke down. I said, ‘I hate Covid. Why won’t you even let me have a small victory?’”Dr. Emond said, “Once we got over, ‘Would he survive?’ in our minds was, ‘Will he be able to be a doctor again?’ He suffered. He paid a huge price.”But the brain hemorrhage and clot turned out to be minor. Mentally, Dr. Kato quickly recovered.About a week after coming off the ventilator, he said, “I woke up in my mind.”Physically, he struggled. He had lost 25 pounds, nearly all of it muscle. He needed a feeding tube. He was so weak that one day it took him an hour to reach the device to adjust the incline of his bed, and when he finally got it, he was too weak to push the button. His hair fell out. A shoulder injury from the way he had been positioned kept him from fully raising one arm, and some of his neck and back muscles had wasted away. He needed extensive physical therapy.His family could not visit. Painful as that was for them, he said, it may have been just as well that they never saw him at his worst, in a web of tubes and machines in the intensive care unit.In late May 2020, after two months in the hospital, he went home, his departure cheered by about 200 staff members, chanting “Kato! Kato!”‘He was back.’In August, he began performing surgery again. For the first operation, a hernia repair, he used a robotic device that allowed him to work sitting down.“It was a really big day for everybody,” Dr. Emond said. “A lot of us went in to see how it was going.”By September, Dr. Kato was performing liver transplants, with his sore shoulder wrapped in athletic tape.“He was back,” Dr. Emond said. “I think he was working exceptionally hard to prove to himself and everybody else that he was back.”After two months in the hospital, Dr. Kato was discharged in May 2020. By August, he was performing surgery again.Joshua Bright for The New York TimesHis first transplant patient wound up staying in the same hospital room where Dr. Kato had been, and they snapped a picture together.“From there, I’m kind of full speed,” Dr. Kato said. By March of this year, he had completed 40 transplants and 30 other operations.Memories of his own recovery have tempered his dealings with patients.“I can be much more on their side, in their shoes, in their thinking,” he said.He so disliked the thickened liquids used to help restore swallowing ability that now, he is less inclined to push them on reluctant patients.“It just tastes so horrible,” he said. “I really cannot blame anybody who cannot take it. A few weeks ago, a patient complained about the thickened milk. In the past I would have just said, ‘You have to do this to get better.’ Now I can say, ‘Maybe you don’t have to do it.’ Each patient may have a different way.”He even offers tips on the hospital menu.“The patient hates the food, I hate the food, but I know the Cajun shrimp is a little better,” he said. Protein drinks? “I recommend the strawberry flavor.”When he was taken off the ventilator, at first he could not speak.“I learned that when you cannot talk, it does not mean you are not thinking,” he said. “The mind is so clear.”Facing death has also brought his career and his goals into a sharper focus, he said.“You don’t really want to waste your time, because you never know — one day all of a sudden you are in this situation,” he said.He realized, he said, that he must recruit more surgeons to continue the work that he and his foundation had started, to bring liver transplants to children in Latin America.“If I died and nobody else picks it up, that’s a problem,” he said.He also feels driven to promote and teach others to perform the complex cancer operations that involve removing multiple organs to reach a tumor, and then putting the organs back in.“This cannot be just my thing forever,” he said “It has to be everybody’s.”

Read more →