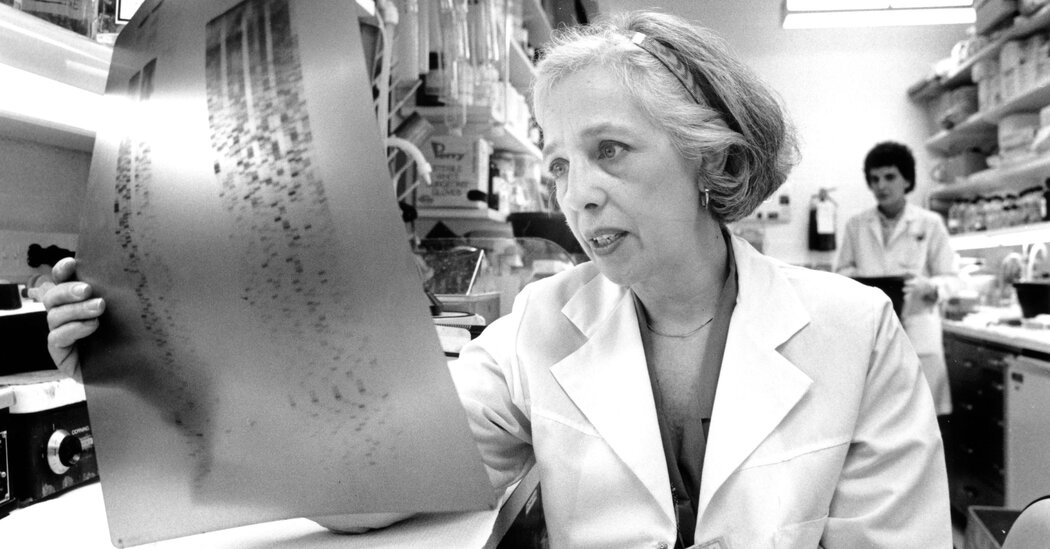

She and her husband invented a dip-and-read paper strip that greatly simplified the diagnosis of the disease and paved the way for home test kits.Helen Murray Free, a chemist who ushered in a revolution in diagnostic testing when she co-developed the dip-and-read diabetes test, a paper strip that detected glucose in urine, died on Saturday at a hospice facility in Elkhart, Ind. She was 98.The cause was complications of a stroke, her son Eric said.Before the invention of the dip-and-read test in 1956, technicians added chemicals to urine and then heated the mixture over a Bunsen burner. The test was inconvenient, and, because it could not distinguish glucose from other sugars, results were not very precise.Working with her husband, who was also a chemist, Ms. Free figured out how to impregnate strips of filter paper with chemicals that turned blue when glucose was present. The test made it easier for clinicians to diagnose diabetes and cleared the way for home test kits, which enabled patients to monitor glucose on their own.People with diabetes now use blood sugar meters to monitor their glucose levels, but the dip-and-read tests are ubiquitous in clinical laboratories worldwide.Helen Murray was born on Feb. 20, 1923, in Pittsburgh to James and Daisy (Piper) Murray. Her father was a coal company salesman; her mother died of influenza when Helen was 6.She entered the College of Wooster in Ohio in 1941, intent on becoming an English or Latin teacher. But she changed her major to chemistry on the advice of her housemother; World War II was creating new opportunities for women in a field that had been a male preserve.“I think that was the most terrific thing that ever happened, because I certainly wouldn’t have done the things I have done in my lifetime,” Ms. Free recalled in a commemorative booklet produced by the American Chemical Society in 2010.She received her bachelor’s degree in 1944 and went to work for Miles Laboratories in Elkhart, first in quality control and then in the biochemistry division, which worked on diagnostic tests and was led by her future husband, Alfred Free. They married in 1947.Ms. Free during the 2000s performing glucose-testing experiments with schoolchildren. via National Inventors Hall of FameHe provided the ideas; she was the technician “who had the advantage of picking his brain 24 hours a day,” Ms. Free recalled in an interview for this obituary in 2011. They soon set their sights on developing a more convenient glucose test “so no one would have to wash out test tubes and mess around with droppers,” she said. When her husband suggested chemically treated paper strips, “it was like a light bulb went off,” she said.They faced two challenges. First, they needed to refine the test so that it would detect only glucose, the form of sugar that is found in the urine of people with diabetes. Second, the chemicals they needed to use were inherently unstable, so they had to find a way to keep them from reacting to light, temperature and air.The first problem was easily solved with the use of a recently developed enzyme that reacted only to glucose. To stabilize the chemicals, the Frees experimented with rubber cement, potato starch, varnish, plaster of Paris and egg albumin before settling on gelatin, which appeared to work best.With her husband, Ms. Free wrote two books on urinalysis. Later in her career she returned to school, earning a master’s in clinical laboratory management from Central Michigan University in 1978 at age 55. She held several patents and published more than 200 scientific papers.At Miles, she rose to director of clinical laboratory reagents and later to director of marketing services in the research division before retiring in 1982; by then the company had been acquired by Bayer. She was elected president of the American Chemical Society in 1993. In 2009, she was awarded a National Medal of Technology and Innovation by President Barack Obama, and in 2011 she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, N.Y., for her role in developing the dip-and-read test.Ms. Free receiving the National Medal of Technology and Innovation from President Barack Obama in 2011 in a White House ceremony. She was also inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.J. Scott Applewhite/Associated PressAlfred Free died in 2000. In addition to her son Eric, Ms. Free is survived by two other sons, Kurt and Jake; three daughters, Bonnie Grisz, Nina Lovejoy and Penny Maloney; a stepson, Charles; two stepdaughters, Barbara Free and Jane Linderman; 17 grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren.Miles Laboratories followed the introduction of the dip-and-read glucose test with a host of other tests designed to detect proteins, blood and other indicators of metabolic, kidney and liver disorders. “They sure went hog wild on diagnostics, and that’s all Al’s fault,” Ms. Free said in the commemorative booklet. “He was the one who pushed diagnostics.”It wasn’t all smooth sailing. Several years after the introduction of the dip-and-read test, Miles moved Ms. Free to another division, citing an anti-nepotism policy. But two years later, after a change in management, she was transferred back to her husband’s division.“They realized that breaking up a team like this was interfering with productivity in the lab,” Ms. Free said.

Read more →