Why Liberal Suburbs Face a New Round of School Mask Battles

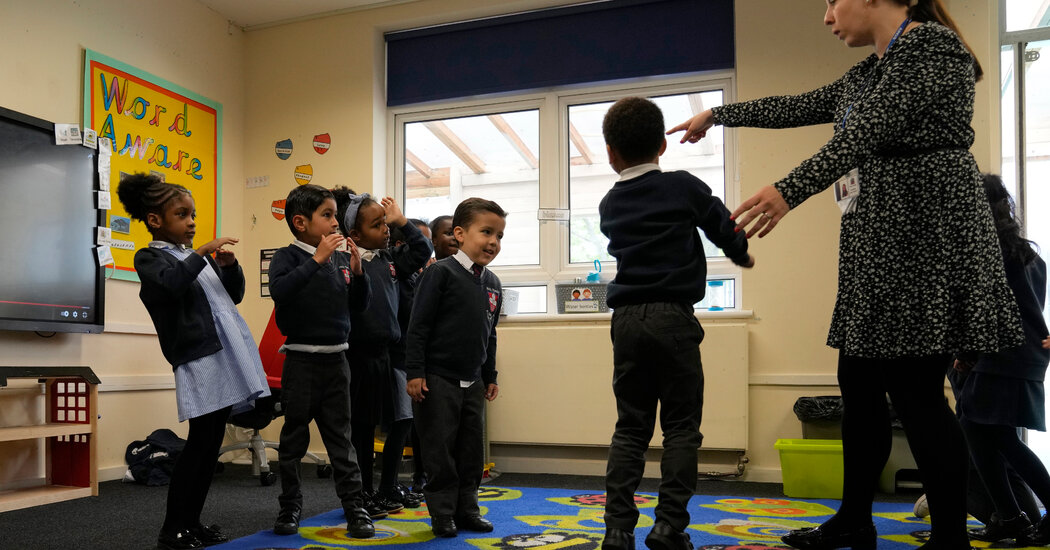

With the end of many statewide mask mandates, it’s up to local districts whether they will keep the requirement. Communities anticipate political and emotional fights ahead.David Fleishman, the superintendent of schools in Newton, Mass., an affluent Boston suburb, said he recently received a message from a parent who pushed for ending mask mandates in classrooms.But first, he said, the individual felt the need to assure him, “I am not a Trump supporter.”While Newton, like much of Massachusetts, is mostly liberal and Democratic, Mr. Fleishman said that when it comes to masks, “there’s this tension.”The battle over mask mandates may be moving to liberal-leaning communities that had been largely in agreement on the need for masking — and bound by statewide mask requirements.Now that Massachusetts will lift its school mask mandate on Feb. 28, joining other liberal states like New Jersey and Connecticut, it will be up to individual school districts like Newton, and nearby Boston, to decide whether and how quickly they want to rescind their own mask rules.They will do so under a barrage of conflicting public health guidance, with Ivy League, government and medical experts offering competing advice.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics continue to call for school masking, and some polls show that the public is broadly supportive of the practice.Districts must decide whether to end mask mandates at schools like Countryside Elementary School, where Ms. Szwarcewicz teaches.Tony Luong for The New York TimesBut a well-organized chorus of public health and child development experts, alongside parent activists, say that masking can hurt children academically and socially, and are calling for the return to a semblance of normalcy.Newton and Boston, about 10 miles apart, give an idea of how two politically liberal and cautious districts are approaching the choice — and how and why they may come to different decisions. The debate will involve science, but also politics, race and class, as well as a swell of emotions.Some see masking as a potent health tool and a symbol of progressive values. Others have come to see face coverings as an unfortunate social barrier between their children and the world. And many people are somewhere in between.In Newton, 65 percent of elementary school students, 79 percent of middle schoolers and 88 percent of high schoolers are vaccinated, according to the district. The district is 61 percent white, and 14 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.Some prominent leaders in the community say they are ready to relax restrictions.In Boston, where vaccination rates are somewhat lower — significantly so for Black and Latino children, who make up most of the district — the public school district says it has no plan to end its mask mandate.Teachers’ unions have been among the strongest supporters of masking, pushing in recent weeks for their members and students to have access to medical-grade masks.Tony Luong for The New York TimesNeither do some of the city’s charter schools.David Steefel-Moore, director of operations for the MATCH charter school network, said he had heard “no negative blowback” on masking from parents, who are overwhelmingly Black and Latino. “We have the other side of that: ‘My child told me there is a kid in their class with the mask down around their neck. What are you doing about that?’”For students in Boston who may be living with a grandparent or family member with underlying health issues, the end of mandatory masking could put children and teenagers in the uncomfortable position of having to choose between their family’s sense of safety and fitting in at school, said Gayl Crump Swaby, a Boston Public Schools parent and professor of counseling who specializes in issues of trauma for families of color.“They should not have to be making these kinds of decisions; they are young,” she said.Some parents might even prefer online schooling to classrooms with unmasked peers and teachers, she added.In Newton, one of the most prominent voices in the masking debate is Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, and a parent of students in the district. He serves on the district’s medical advisory group, and has become an outspoken advocate for unmasking children as Omicron recedes.The group will meet this month to formulate a recommendation on masking for the elected school committee, which will make the final decision.Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, is a Newton parent and supports ending the district’s school mask mandate: “If not now, when?”Elise Amendola/Associated PressDr. Jha does not believe that his own children have been seriously harmed from masking, and does not believe that the pandemic is over.But he wants to unmask soon, he says, in part to offer some social and academic normalcy, given that he thinks future coronavirus surges in the United States are likely to require masking again — potentially in the South over the summer and in the North this fall and next winter.He argued that with new therapeutics to treat Covid-19, there is little upside this spring to masking in regions, like the Boston area, with relatively high vaccination rates and plummeting infections.“If not now, when?” he asked. “Because I don’t foresee a time in the next couple of years that will necessarily be that much better.”Vulnerable teachers and students, he said, could stay safe by wearing high-quality masks even when those around them are not covered. Throughout the pandemic, he pointed out, virus transmission inside schools has been limited, including in some places where masks have not been required.Dr. Jha’s advice, however, is not necessarily reassuring to educators who have seen guidelines change frequently over the past two years.The Coronavirus Pandemic: Key Things to KnowCard 1 of 3Some mask mandates ending.

Read more →