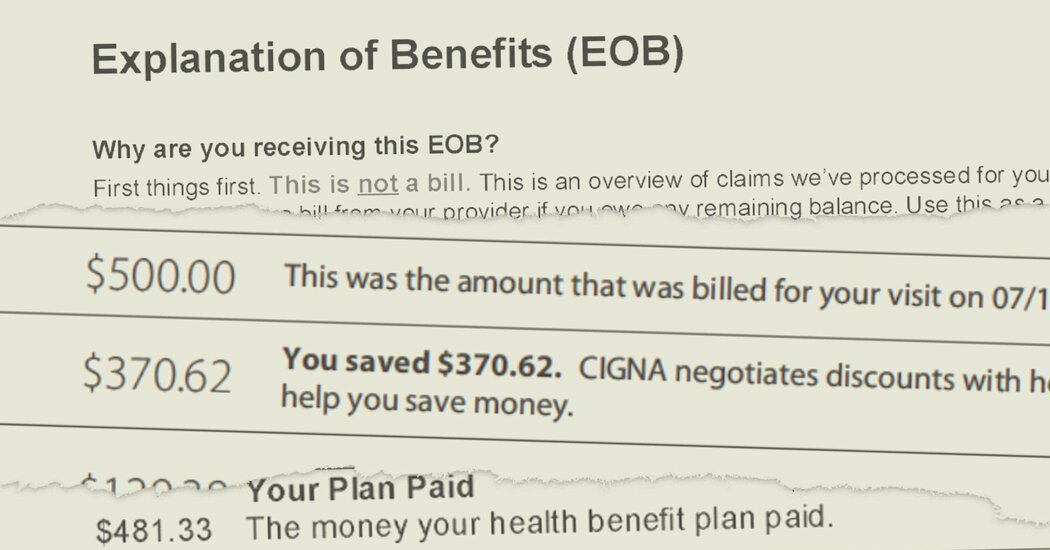

A data analytics firm has helped big health insurers cut payments to doctors, raising concerns about possible price fixing.Recent revelations about a data analytics firm’s role in determining medical payments have heightened concerns about possible price fixing in health care and led to a call for a federal investigation.In a letter this week, Senator Amy Klobuchar asked federal regulators to examine whether algorithms used by the firm, MultiPlan, have helped major health insurers conspire to cut payments to doctors and leave patients with large bills. She cited a New York Times investigation last month into MultiPlan’s dominance of the lucrative business of pricing out-of-network medical claims.“Algorithms should be used to make decisions more accurate, appropriate and efficient, not to allow competitors to collude to make health care more costly for patients,” Ms. Klobuchar wrote to the heads of the Justice Department’s antitrust division and the Federal Trade Commission.When patients see a medical provider outside their plan’s network, insurers often send their claims to MultiPlan, which uses proprietary algorithms to recommend how much to pay. By driving down payments to providers, MultiPlan and the insurers can collect higher fees for themselves, The Times reported, but this can lead to higher bills for patients, who may get charged the unpaid balance.UnitedHealthcare, Cigna, Aetna and other major insurers use MultiPlan’s pricing recommendations, and the firm has boasted to investors that it is “deeply embedded” in its clients’ claims-processing systems.In interviews, Ms. Klobuchar, a Democrat from Minnesota, and experts in antitrust law said this arrangement could amount to price fixing: Rather than competing to offer better coverage, insurers could use the low prices recommended by MultiPlan’s algorithms, knowing their competitors would likely do the same.“This should trigger an investigation by the agencies,” said Barak Orbach, a law professor at the University of Arizona. “There seems to be a really strong case.”The F.T.C. and Justice Department declined to comment, but both agencies have raised concerns in the past about similar arrangements in other industries.“Algorithms should be used to make decisions more accurate, appropriate and efficient, not to allow competitors to collude to make health care more costly for patients,” Senator Amy Klobuchar wrote in a letter to antitrust regulators.Valerie Plesch for The New York TimesMultiPlan did not have an immediate comment. But in legal filings, the firm has denied allegations of collusion and said that insurers are free to reject its pricing recommendations or negotiate higher payments with providers.The firm said in a previous statement to The Times that its work benefits patients and employers who pay for their workers’ coverage by “promoting affordability, efficiency and fairness across the U.S. health care system.”Insurers have said that MultiPlan’s tools help combat outrageous billing by some providers, including consolidated hospital systems and private-equity-backed staffing firms.Documents reviewed by The Times indicate that MultiPlan has sometimes told insurers how their unnamed competitors were using the firm’s pricing tools. In a 2017 presentation to UnitedHealthcare, MultiPlan shared “Recent Client Strategies to Improve Results,” which included techniques that could reduce payments to providers.After a 2019 meeting, a UnitedHealthcare senior vice president reported to her colleagues that a MultiPlan executive “did not specifically name competitors but from what he did say we were able to glean who was who.” She then described how Cigna, Aetna and some Blue Cross Blue Shield plans were apparently using the firm’s pricing tools.Three hospital systems have sued MultiPlan, accusing it of colluding with major insurers to set unreasonably low payments for medical care, and patients and providers have complained to the F.T.C. about MultiPlan, records obtained through a public records request show.One provider reported slashed payments from UnitedHealthcare, Cigna and an Aetna subsidiary after the insurers routed claims to MultiPlan’s most aggressive pricing tool. Another said the tool “has decimated my life” and caused “the closing of my business,” which has “left patients having to travel 2.5 hrs for surgery.”Patients complained to the agency of receiving large bills after insurers used MultiPlan-recommended prices. “This is now affecting my credit score,” wrote one patient, describing a bill that had been sent to a debt collector. Another reported being billed thousands of dollars “since they refuse to pay my providers the correct amount.”Pricing algorithms have driven MultiPlan’s growth over the past 15 years. The firm previously focused on controlling costs by negotiating with medical providers, but after being sold to private equity investors, it embraced automated, algorithm-based tools, which typically yield lower payment recommendations.Access to data from hundreds of clients has helped entrench the firm’s dominance, executives have told investors. “We build our algorithms on a much larger data lake,” one executive said in a 2020 presentation.The focus on MultiPlan’s automated pricing tools highlights growing concern among regulators and some in Congress that algorithms are supercharging price-fixing schemes and driving up costs for consumers.During the Biden administration, companies’ increasing embrace of technological advancements has collided with aggressive enforcement efforts by regulators. The results have been mixed, as the agencies seek to apply laws enacted to combat 19th-century oil and railroad robber barons to 21st-century technology firms.“Algorithms are the new frontier,” the Justice Department wrote in a brief in one case. “And, given the amount of information an algorithm can access and digest, this new frontier poses an even greater anticompetitive threat than the last.”Regulators and some antitrust scholars worry that algorithms can enable sophisticated collusion that is difficult to police. Competitors no longer need to meet in secret to hatch a conspiracy and communicate among themselves to perpetuate it. They can simply agree to use a common pricing algorithm.Weighing in on private lawsuits involving apartment rents and hotel room prices, the agencies have argued that such an arrangement is illegal, even if competitors agree with a wink and a nod rather than a formal pact.But in one case, a judge disagreed in a December ruling, allowing the lawsuit to go forward but requiring renters to offer more explicit evidence that landlords had conspired to raise prices using an algorithm.Ms. Klobuchar has introduced legislation that would effectively make the agencies’ position the default. Courts would presume it illegal for competitors to share nonpublic data with a middleman and use the pricing recommendations that the firm’s algorithms produced.“It is not clear whether current antitrust laws are sufficient to stop this practice,” Ms. Klobuchar said in an interview. “It is much better just to clarify this and to close the loophole.”The bill would also require companies to tell consumers if they are buying something that was priced using an algorithm, and it would give regulators greater authority to demand details about how an algorithm works.

Read more →