Behind the Scenes, McKinsey Guided Companies at the Center of the Opioid Crisis

Behind the Scenes, McKinsey Guided Companies at the Center of the Opioid Crisis

#27-mack-top {

max-width: 100% !important;

}

header svg {

fill: #121212 !important;

}

#link-78f0544a {

display: none;

}

#headline {

display: flex;

font-family: ‘nyt-cheltenham’;

font-weight: 700;

font-style: italic;

font-size: 26px;

line-height: 29px;

text-align: center;

max-width: 940px;

margin: auto;

margin-bottom: 60px;

-webkit-font-smoothing: antialiased;

-moz-osx-font-smoothing: grayscale;

}

.NYTApp #headline {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

}

#top-wrapper {

display: flex;

width: 100%;

height: 100vh;

flex-direction: column;

}

.image-wrapper {

display: flex;

margin: auto;

max-width: 610px;

margin-top: 0;

}

@media (min-width: 940px) {

#top-wrapper {

min-height: 900px;

}

#headline {

font-size: 55px;

line-height: 60px;

margin-bottom: auto;

}

}

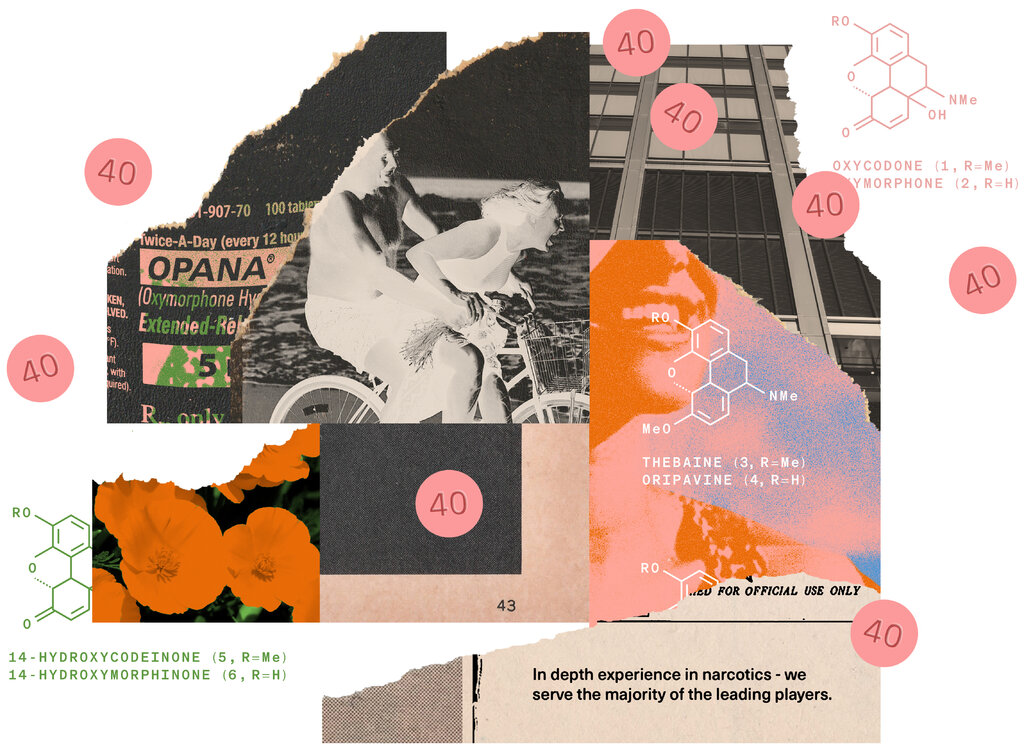

Supported byContinue reading the main storyBehind the Scenes, McKinsey Guided Companies at the Center of the Opioid CrisisThe consulting firm offered clients “in-depth experience in narcotics,” from poppy fields to pills more powerful than Purdue’s OxyContin.Send any friend a storyAs a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.Chris Hamby and The reporters pored over a trove of more than 100,000 documents to investigate McKinsey’s unknown work for opioid makers.June 29, 2022, 6:15 p.m. ETIn patches of rural Appalachia and the Rust Belt, health authorities were sounding alarms that a powerful painkiller called Opana had become the drug of choice among people abusing prescription pills.It was twice as potent as OxyContin, the painkiller widely blamed for sparking the opioid crisis, and was relatively easy to dissolve and inject. By 2015, government investigations and scientific publications had linked its misuse to clusters of disease, including a rare and life-threatening blood disorder and an H.I.V. outbreak in Indiana.Opana’s manufacturer, the pharmaceutical company Endo, had scaled back promotion of the drug. But months later, the company abruptly changed course, refocusing resources on the drug by assigning more sales representatives.The push was known internally as the “Sales Force Blitz” — and it was conducted with consultants at McKinsey & Company, who had been hired by Endo to provide marketing advice about its chronic-pain medicines and other products.

.document-tear {

width: 100%;

margin: auto;

margin-bottom: 40px;

margin-top: 30px;

padding-top: 20px;

padding-bottom: 20px;

border: 0.0px solid #d3d0d0;

max-width: 600px;

box-shadow: 0px 1px 5px -1px #afa8a8;

}

.document-tear.doc-img {

margin-bottom: 15px;

}

.document-tear u {

text-decoration: none;

background-color: #FFF8B9;

padding-top: 1.5px;

padding-bottom: 1.5px;

}

.document-tear strong {

text-decoration: none;

background-color: #121212;

padding-top: 1.5px;

padding-bottom: 1.5px;

color: #121212

}

.document-tear h4 {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

font-weight: 800;

font-size: 13px;

margin-bottom: 15px;

text-transform: uppercase;

padding-bottom: 10px;

border-bottom: 1px solid;

}

.document-tear p {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

font-weight: 200;

font-size: 18px;

line-height: 26px;

}

.document-tear a {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

display: inline-block;

font-weight: 500;

font-size: 14px;

text-align: right;

color: #326891;

text-decoration: underline;

}

.document-tear img {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

margin: auto;

display: block;

}

.doc-caption {

font-size: 0.875rem;

line-height: 1.125rem;

font-family: ‘nyt-imperial’;

color: #727272;

max-width: 600px;

margin: auto;

margin-bottom: 40px;

}

@media (min-width: 740px) {

font-size: 0.9375rem;

line-height: 1.25rem;

}

McKinsey Settlement Documents

A campaign by McKinsey and Endo to push the company’s chronic-pain products, including Opana.The untold story of McKinsey’s work for Endo was among the revelations found by The New York Times in a repository of more than 100,000 documents obtained by a coalition of state attorneys general in a legal settlement related to McKinsey’s opioid work.Much has been disclosed over the years about McKinsey’s relationship with Purdue Pharma, including the consulting firm’s recommendation that the drug maker “turbocharge” its sales of OxyContin. But The Times found that the firm played a far deeper and broader role in advising clients involved in the opioid crisis than was publicly disclosed.The McKinsey records include more than 15 years of emails, slide presentations, spreadsheets, proposals and other documents. They provide a sweeping and detailed depiction of a firm that became a trusted adviser to companies at the core of an epidemic that has claimed half a million American lives.While the firm held remarkable sway at Purdue, it also advised the largest manufacturer of generic opioids, Mallinckrodt. It worked with Endo on marketing Opana and helped it grow into a leading generics manufacturer. It advised Johnson & Johnson, whose subsidiary Tasmanian Alkaloids was the largest supplier of the raw materials extracted from poppies used to make many top-selling opioids. Then, as the full brunt of the epidemic became apparent, it counseled government agencies on how to address the fallout.McKinsey’s opioid clients already wanted to grow their businesses. What the firm offered was know-how and sophistication, the documents show, and, as it noted in one presentation, “in-depth experience in narcotics.”The Massachusetts attorney general, Maura Healey, who helped craft the settlement, said in a statement that “as Americans were dying from the opioid epidemic, McKinsey was trading on its reputation and connections to make the crisis worse.” She added that the newly released documents “expose McKinsey’s role in the opioid crisis and will inform policymakers’ efforts to prevent this from happening again.”Drawing on reams of data and proprietary tools, McKinsey vetted deals and advised on corporate strategy. It developed tactics for dealing with regulators and helped secure approval for new products.The firm helped clients adopt more aggressive sales strategies, which, on at least two occasions, led companies to shift resources to more potent products. It profiled and targeted physicians, in some instances trying to influence prescribing habits in ways that federal officials later warned heightened the risk of overdose.And when opioid prescriptions began to decrease during a government crackdown, the records show, McKinsey devised new approaches to drive sales.McKinsey agreed to provide the documents to the attorneys general last year as part of a nearly $600 million settlement in which it admitted no wrongdoing. The firm has since apologized for its advice to opioid makers but, in a statement on Wednesday, suggested that its work with companies other than Purdue was “much more limited” and that it “did not counsel or recommend to Endo that it promote Opana more aggressively.”“We recognize the terrible consequences of the opioid epidemic and have acknowledged our role in serving opioid manufacturers,” said a McKinsey spokesman. “We stopped that work in 2019, have apologized for it and have been focused on being part of the solution.”An Endo spokeswoman declined to comment on the company’s work with McKinsey, citing litigation. She instead referred to a company statement saying that in September 2016 Endo had “stopped promoting opioid products to health care professionals” and eliminated its opioid-focused sales force.Mallinckrodt declined to comment. Johnson & Johnson, in a statement, maintained that all its actions were appropriate, while Purdue said that it was focused on ending bankruptcy proceedings so it could reorganize into a new, more “public-minded” company that would “deliver billions of dollars of value” toward abating the opioid crisis and compensating victims.‘Opana Patients’Dr. Steven Butler, a kidney specialist serving a largely rural stretch of East Tennessee, helped with an unusual case in fall 2012. A woman in her 20s had arrived at the Holston Valley Medical Center in Kingsport with an array of symptoms — she was anemic, and her kidneys appeared to be failing — that resembled a rare blood disorder.A few days later, another patient with similar symptoms arrived at the hospital. Then a third. Dr. Butler called the Tennessee Department of Health, which launched an investigation. Over the following months, more patients appeared.As they underwent time-consuming treatments, some acknowledged they had dissolved and injected a pill whose name Dr. Butler had never heard before: Opana ER.The Opioid CrisisFrom powerful pharmaceuticals to illegally made synthetics, opioids are fueling a deadly drug crisis in America.An Unrelenting Surge: Deaths from drug overdoses again rose to record-breaking levels in 2021. Here is how to talk to your family about the threat opioids pose.Youth Deaths: Young people are turning to social media to find prescription pills. But drugs found this way are often laced with deadly doses of fentanyl.A Settlement: Purdue Pharma reached a deal with a group of states that long resisted the structure of the original bankruptcy plan. Here is what the agreement means.Detailing Tragedies: As part of the settlement, families who lost loved ones to opioid addiction were allowed to address the owners of Purdue Pharma in court.“Locally, it became a very well-described phenomenon,” he recalled. “They were just called ‘Opana patients,’ as though that was a real common thing.”The tangled path that led to Opana’s rise illustrates McKinsey’s deep involvement in the opioid business, with its work for one client rippling out with consequences for others.Years earlier, the firm had helped usher the drug onto the market, advising Endo’s partner, Penwest Pharmaceuticals, on its launch in 2006. Two years later, the documents show, McKinsey performed a project for Purdue that paved the way for Endo to extend Opana’s reach.Purdue was seeking approval from the Food and Drug Administration for a new version of OxyContin that would be more difficult to snort or inject. After the F.D.A. denied its application in 2008, Purdue enlisted McKinsey’s help. The consultants interviewed a former drug dealer about OxyContin abuse, oversaw scientific studies, prepared regulatory documents and coached company officials on how to deal with the F.D.A., which had been a McKinsey client. The agency gave its approval in 2010, and later allowed Purdue to claim the new pills were resistant to abuse.Soon, OxyContin sales declined — while Opana sales rose. In an internal document, Endo attributed the uptick in part to “patient dissatisfaction with new OxyContin formulation.” Data on abuse showed similar trends: a decline for OxyContin and a rise for Opana.Endo later developed a new version of Opana it wanted to promote as abuse-resistant. The F.D.A. found that the new pills “demonstrated a minimal improvement in resistance to tampering by crushing,” and that they were “readily abusable” by injection. The agency allowed the drug to enter the market in early 2012, but without being labeled as resistant to abuse.Cooking Opana in order to inject it, on a stove in West Virginia.Mark TrentWithin months, Dr. Butler saw his first Opana patient. In October 2012, both the F.D.A. and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put out health alerts about the blood syndrome. Then another cluster appeared, in North Carolina, and other cases in Arkansas, Florida, Pennsylvania and South Carolina.To make matters worse, according to the F.D.A., the new version of Opana drove many users to switch from snorting to injecting, considered a riskier form of abuse. The likely cause of the blood disorder, researchers determined, was the very substance that Endo had added to make the pills harder to crush. When dissolved and injected, it could trigger rapid red blood cell destruction and organ damage.Rajiv De Silva, formerly of McKinsey, took over Opana’s manufacturer, Endo, in 2013.BusinesswireAs concerns about Opana grew, Endo hired a new chief executive in 2013: Rajiv De Silva, a former leader within McKinsey’s pharmaceutical practice who soon tapped the firm to help chart a growth strategy.A few months after Mr. De Silva took over, McKinsey helped Endo execute a complicated maneuver known as a “tax inversion” — a legal form of tax avoidance that the Obama administration would decry as an “abuse” of the system. For tax purposes, the Pennsylvania company was now based in Ireland, where the rate was substantially lower.Endo’s offices in Dublin. With the help of McKinsey, it moved its headquarters out of the U.S. for tax purposes.Paulo Nunes dos Santos for The New York TimesThe move, which sent Endo’s stock price climbing, was “a tax play to set up doing a lot of deals,” according to a 2014 email from a McKinsey partner named Dr. Arnab Ghatak, who also helped lead the firm’s work with Purdue.Endo went on a buying spree and would soon become one of the largest U.S. manufacturers of generic opioids.‘The Narcotics Franchise’The production of pills by companies like Endo and Purdue depended on a complex and tightly regulated global supply chain stretching from the fields of Tasmania to factories in the American heartland.Here, too, was McKinsey.Long before a patient in the United States filled a prescription for OxyContin, a farmer on another continent harvested a poppy rich in a substance called thebaine. Tasmanian Alkaloids, the Johnson & Johnson subsidiary, controlled the majority of this market.From far-flung fields and extraction facilities, the raw materials made their way to American processing plants. The top U.S. producers at this stage were another Johnson & Johnson subsidiary, Noramco, and Mallinckrodt, the big generics manufacturer.The documents reveal McKinsey’s work advising them behind the scenes. By the firm’s own account, it had deep expertise in the international trade of legal narcotics. “We serve the majority of the leading players,” the consultants wrote in a 2009 memo.That year, the firm oversaw a project for Johnson & Johnson titled “Maximizing the Value of the Narcotics Franchise.” In a presentation set against an image of a poppy field, the consultants advised the company on how it could invest to further strengthen its already-dominant position or sell the business if the price was right.

.document-tear {

width: 100%;

margin: auto;

margin-bottom: 40px;

margin-top: 30px;

padding-top: 20px;

padding-bottom: 20px;

border: 0.0px solid #d3d0d0;

max-width: 600px;

box-shadow: 0px 1px 5px -1px #afa8a8;

}

.document-tear.doc-img {

margin-bottom: 15px;

}

.document-tear u {

text-decoration: none;

background-color: #FFF8B9;

padding-top: 1.5px;

padding-bottom: 1.5px;

}

.document-tear strong {

text-decoration: none;

background-color: #121212;

padding-top: 1.5px;

padding-bottom: 1.5px;

color: #121212

}

.document-tear h4 {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

font-weight: 800;

font-size: 13px;

margin-bottom: 15px;

text-transform: uppercase;

padding-bottom: 10px;

border-bottom: 1px solid;

}

.document-tear p {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

font-weight: 200;

font-size: 18px;

line-height: 26px;

}

.document-tear a {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

display: inline-block;

font-weight: 500;

font-size: 14px;

text-align: right;

color: #326891;

text-decoration: underline;

}

.document-tear img {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

margin: auto;

display: block;

}

.doc-caption {

font-size: 0.875rem;

line-height: 1.125rem;

font-family: ‘nyt-imperial’;

color: #727272;

max-width: 600px;

margin: auto;

margin-bottom: 40px;

}

@media (min-width: 740px) {

font-size: 0.9375rem;

line-height: 1.25rem;

}

McKinsey Settlement Documents

A presentation McKinsey prepared for Johnson & Johnson, whose subsidiaries played key roles in the opioid supply chain.For Mallinckrodt, McKinsey consultants walked factory floors and monitored production data, recommending how the company might coax greater yields from the same base of raw materials and speed up manufacturing lines.In 2016, McKinsey prepared Mallinckrodt for negotiations with companies that sourced generic drugs for Walmart and CVS, and advised on dealing with the Drug Enforcement Administration. The D.E.A. had set production limits to prevent an oversupply of pills, and McKinsey counseled Mallinckrodt on how it could use logistical tactics to secure a higher quota while maintaining a “friendly relationship” with the agency.“To suggest this work was intended to undermine relevant laws or regulations would be false,” the McKinsey spokesman said.McKinsey consultants also took jobs at the opioid manufacturers themselves. A partner in the firm’s pharmaceutical practice, Frank Scholz, became Mallinckrodt’s senior vice president of global operations in 2014 and later was promoted to president of its generics business.But it was the arrival of Mr. De Silva at Endo that brought a particular opportunity for McKinsey. In late 2014, the company asked the consultants to provide advice on structuring the company’s sales force. This soon evolved into a more detailed project in an area where McKinsey excelled: how to dispatch hundreds of sales representatives to maximum effect.Shifting to OffenseMcKinsey had a playbook for seemingly any problem a pharmaceutical company might face, from production snags to generic competition to inquisitive regulators. But the firm had a particular penchant for sales and marketing.In the years leading up to its work on Opana, McKinsey had built increasingly powerful tools for getting the right messages in front of the right physicians, and the firm had honed them in numerous opioid-marketing projects, including two for Johnson & Johnson.While the broad strokes of these efforts have been known, the documents provide an unprecedented look inside McKinsey’s tool kit. The records related to the firm’s work for Purdue are particularly detailed, providing insight into the strategies that consultants used for other companies.In 2009, the firm recommended a technique known as segmentation. The best marketing campaigns — whether for food, cars or electronics — divided consumers into segments based on how they acted and thought, then developed tailored messages to win them over, the consultants said.In Purdue’s case, the customer was a physician with a license to prescribe controlled substances, and the product was OxyContin.The consultants interviewed dozens of physicians and solicited the views of hundreds more in a survey. Four groups of doctors emerged, each with a distinct profile. The consultants then developed messages to appeal to each group’s practical and emotional needs.

.document-tear {

width: 100%;

margin: auto;

margin-bottom: 40px;

margin-top: 30px;

padding-top: 20px;

padding-bottom: 20px;

border: 0.0px solid #d3d0d0;

max-width: 600px;

box-shadow: 0px 1px 5px -1px #afa8a8;

}

.document-tear.doc-img {

margin-bottom: 15px;

}

.document-tear u {

text-decoration: none;

background-color: #FFF8B9;

padding-top: 1.5px;

padding-bottom: 1.5px;

}

.document-tear strong {

text-decoration: none;

background-color: #121212;

padding-top: 1.5px;

padding-bottom: 1.5px;

color: #121212

}

.document-tear h4 {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

font-weight: 800;

font-size: 13px;

margin-bottom: 15px;

text-transform: uppercase;

padding-bottom: 10px;

border-bottom: 1px solid;

}

.document-tear p {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

font-weight: 200;

font-size: 18px;

line-height: 26px;

}

.document-tear a {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

font-family: ‘nyt-franklin’;

margin: auto;

display: inline-block;

font-weight: 500;

font-size: 14px;

text-align: right;

color: #326891;

text-decoration: underline;

}

.document-tear img {

width: calc(100% – 40px);

margin: auto;

display: block;

}

.doc-caption {

font-size: 0.875rem;

line-height: 1.125rem;

font-family: ‘nyt-imperial’;

color: #727272;

max-width: 600px;

margin: auto;

margin-bottom: 40px;

}

@media (min-width: 740px) {

font-size: 0.9375rem;

line-height: 1.25rem;

}

McKinsey Settlement Documents

McKinsey, drawing on data analyses, made personality profiles of doctors to fuel opioid sales.McKinsey identified a particular opportunity in doctors who were hesitant to prescribe OxyContin because of worries about abuse, addiction and possible scrutiny from the D.E.A. These physicians often tried to treat chronic pain with less powerful drugs.Persuading them to switch to OxyContin could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, McKinsey advised. To do this, McKinsey proposed tactics to “raise physician comfort levels through appropriate education and support.” Sales representatives, McKinsey said, should reassure doctors that many of their colleagues prescribed OxyContin and that the drug need not be reserved for extreme pain.In 2014, the F.D.A. introduced new labeling requirements for OxyContin and similar opioids, limiting their use to cases of severe chronic pain in which less risky treatments had proved ineffective. But McKinsey’s strategy had long since been rolled out.Another McKinsey approach, known as targeting, tried to identify doctors who would provide the greatest return on sales representatives’ time.Purdue, dissatisfied with dipping OxyContin sales in 2013, had enlisted McKinsey’s help. Revenues were down, the consultants advised, in large part because of government actions to tamp down the opioid epidemic. Doctors were writing prescriptions for fewer tablets and lower doses, and wholesalers and pharmacies were imposing new controls.Fentanyl Overdoses: What to KnowCard 1 of 5Devastating losses.

Read more →